What is the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI)?

Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) is a specification for a software program that connects a computer's firmware to its operating system (OS). UEFI is expected to eventually replace basic input/output system (BIOS) but is compatible with it. The specification is most often pronounced by naming the letters U-E-F-I.

UEFI is a standard specification that defines how a computer's OS and firmware will interface. Through data tables, and boot and runtime service calls, UEFI makes a standard environment available to boot a system's OS, control the booting process, run pre-boot applications, and pass control of the system to the OS.

UEFI functions via special firmware installed on a computer's motherboard. Specifically, it stores information related to system initialization and startup in an EFI file. The file is stored on the hard disk's EFI System Partition (ESP), a special and independent partition that contains the UEFI bootloader (a set of applications and drivers) and enables the computer to boot the OS. UEFI is programmable, enabling OEM developers to add applications, drivers and UEFI to function as a lightweight OS.

What does UEFI do?

UEFI defines a new method by which OSes and platform firmware communicate, providing a lightweight BIOS alternative that uses only the information needed to launch the OS boot process. In addition, UEFI provides enhanced computer security features and supports most existing BIOS systems with backward compatibility.

The interface contains platform-related data tables and boot and runtime service calls used by the OS loader. Together, this information defines the required interfaces and structures that must be implemented for firmware and hardware devices to support UEFI. UEFI also checks to see which hardware components are attached, wakes up the components and hands them over to the OS.

UEFI's evolution from EFI

In the late 1990s, Intel started the Intel Boot Initiative in recognition of the many limitations of BIOS firmware. The initiative later became the Extensible Firmware Interface or EFI. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines EFI as "a specification for the interface between the operating system and the platform firmware."

Intel developed EFI as an outgrowth of its 64-bit Itanium server architecture, which the company codeveloped with computer maker Hewlett-Packard (HP). The EFI framework was developed in the C programming language. It included numerous commands that were like common disk operating system (DOS) and Linux commands to list a directory's contents, change the directory, move files or directories to a different location, and display help information, for example. Also, like DOS and Linux, EFI could run programs listed in the environmental path from the root.

The industry perceived EFI to address the memory and processing limitations of BIOS in X86 server architectures. Those limitations included 16-bit computing mode, bounded system memory, no independence of in-use CPU, very basic user interface for administrators and tedious assembly language programming. Also, this specification was meant to reduce the dependence of the OS on firmware implementation details and to provide an alternative to legacy BIOS, particularly around ease of use and providing ubiquity across platforms.

A subsequent avatar of EFI, EFI 1.10 also simplified device drivers, reduced driver footprint and enabled deterministic driver selection by the platform. Many computing device vendors released new devices with the 32-bit EFI 1.10 implemented. One example is Apple, which released the MacBook Pro with 32-bit EFI 1.10 in 2006. Intel later developed the EFI Development Kit v2. This version implemented Intel's updated UEFI specification, which added 64-bit support.

EFI remains the property of Intel, and the company still licenses the specification. However, the company ceased sole development of EFI following the release of version 1.10. By then, Intel had also phased out its Itanium processor line, following product delays and other hiccups. Intel contributed EFI 1.10 to the UEFI Forum, an alliance of chipset, hardware, system, firmware and OS vendors. Some of the companies in this industry consortium include the following:

- Microsoft.

- Lenovo.

- HP.

- IBM.

- AMD.

- Apple.

- Dell.

- AMI.

The UEFI Forum developed UEFI, which is based on EFI 1.10, albeit with numerous corrections and changes. In general, the UEFI Forum owns the UEFI specification standard and manages its ongoing development. The group includes contributors that help to build the specification, adopters that use EFI implementations and work groups that handle technical activities, such as designing and developing the test suite and delivering the formal specification.

Current version of UEFI

The emergence of UEFI parallels the increased drive densities used for modern application workloads. The latest version is UEFI 2.10, released in August 2022. Some of the code and protocol names in UEFI 2.10 retain the EFI designation.

UEFI 2.10 is a pure interface specification, defining the interfaces and structures that platform firmware must implement, and that the OS may use in booting. Also, UEFI 2.10 provides a standardized way for the OS and platform firmware to communicate the information necessary for the OS boot process.

UEFI 2.10 features

Users can download the UEFI specification from the UEFI Forum website. There is no charge for using the specification.

UEFI 2.10, released in August 2022 (Errata A released in August 2024), features several enhancements, including the following:

- Extension of platform firmware by loading UEFI driver and UEFI application images.

- Consolidation of boot menus from the OS loader and platform firmware into a single platform firmware menu.

- Option to include legacy boot options, such as booting from the A: or C: drive in the menu.

- Booting from media containing a UEFI OS loader or a UEFI-defined system partition.

- Boot manager to load applications or UEFI drivers from any file on a UEFI-defined file system or by using a UEFI-defined image loading service.

- Common boot environment abstraction for use by UEFI drivers, UEFI applications and UEFI OS loaders.

UEFI vs. BIOS

Turning on a computer kick-starts a chain of events that occurs before the OS is loaded. Firmware rouses the computer's subsystem to execute a series of tests and locates the boot loader, which, in turn, starts the OS kernel. This entire process can be done by either BIOS or UEFI.

In general, BIOS is considered a vestige from earlier computing, whereas UEFI is regarded as the wave of the future. For ease of understanding, some information technology users refer to the processes collectively as UEFI BIOS, despite their substantial differences.

BIOS and UEFI both use low-level software to manage startup functions prior to booting an OS, albeit using different techniques. Also, like BIOS, UEFI is installed at the time of manufacturing and is the first program that runs when booting a computer.

BIOS limitations

BIOS has been in use since the advent of DOS computers in the mid-1970s. BIOS resides on a chip on the machine's motherboard and initializes the central processing unit, random access memory, Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) cards and network devices. BIOS runs a power-on self-test (POST) diagnostic sequence. POST ensures that hardware is configured properly, and all components are functioning as intended.

To accomplish its task, BIOS consults the Master Boot Record to locate the OS and launch the boot loader. MBR uses 32-bit values to describe the offset and length of a partition, thus limiting BIOS systems to 2 terabyte (TB) drives and no more than four partitions.

Also, BIOS runs only in 16-bit processor mode, which limits the number of software commands the firmware can execute at any one time. BIOS allots 1 megabyte of memory in which tasks can be executed. Interfaces and devices thus are initialized sequentially, which can contribute to a sluggish startup.

How UEFI overcomes BIOS limitations

The UEFI specification addresses several limitations of BIOS, including restrictions on hard disk partition size and the amount of time BIOS takes to perform its tasks.

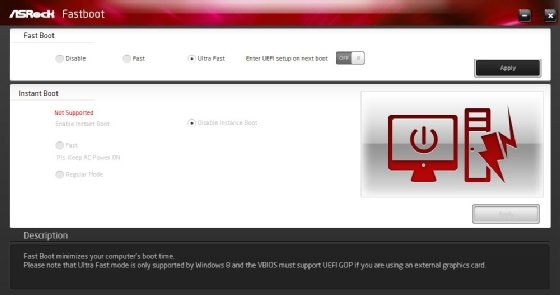

UEFI behaves like a miniaturized OS that sits between firmware and the OS. It performs the same diagnostics as BIOS at startup but offers more flexibility. The OS boots directly in UEFI. This eliminates the need to repeatedly press toggle keys, as is required to boot BIOS.

UEFI stores initialization data in an EFI file partition in non-volatile flash memory, rather than in the firmware. UEFI also can load during boot from a drive or a network share. UEFI also deploys a more flexible partitioning scheme than MBR, known as a Globally Unique Identifier Partition Table, or GPT (also created by Intel as part of EFI). GPT uses 64-bit values to enable the creation of up to 128 partitions and is required for systems launched from 2 TB drives and larger. The EFI partition uses the file allocation table (FAT), including FAT16, FAT32 or virtual FAT.

UEFI phasing out BIOS

Originally developed collaboratively by HP, Intel, Microsoft, Phoenix Technologies and Toshiba, the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) is an open standard for BIOS that governs how much power is delivered to each peripheral device. In 2013, custody of the ACPI was transferred to the UEFI Forum.

Most modern computer systems are equipped to support traditional BIOS, as well as UEFI. In the future, computer manufacturers may continue to support BIOS, but the transition to UEFI has already been underway.

Intel is phasing out BIOS support in newer PCs. Most new desktop PCs, laptops and some tablets bundle UEFI firmware that runs in compatibility support mode for older 32-bit Windows.

As computer makers move away from BIOS, they typically integrate UEFI firmware that runs with Compatibility Support Module (CSM) in modern devices. Although not intended as a long-term solution, CSM enables UEFI-based machines to launch in legacy BIOS mode to work with older Windows versions and other OSes. However, users may want to upgrade to the latest version of the OS to realize the value of UEFI.

Advantages of UEFI

UEFI provides many significant enhancements over BIOS, such as the following:

- Boot mode. Microsoft Windows users can run 32-bit UEFI or 64-bit UEFI, whereas BIOS can only run in 16-bit mode. It's important to note that experts recommend that the OS bit mode and the firmware bit mode should be the same to avoid communication issues during runtime.

- Boot speeds. UEFI enables faster booting and resume times compared to BIOS.

- Drives. UEFI supports boot drives of 2.2 TB and higher capacities, including drives with theoretical capacity of 9.4 zettabytes. That far exceeds the maximum drive capacities available with BIOS. UEFI also supports drives with more than four partitions.

- Drivers. UEFI supports discrete drivers, whereas BIOS drive support is stored in read-only memory, which necessitates tuning it for compatibility when drives are swapped out or changes are made. Simply put, it can be difficult to update UEFI BIOS firmware.

- Graphical user interface (GUI). UEFI enables navigation via a mouse and GUI. It also enables new modules to be added more easily, including device drivers for motherboard hardware and attached peripheral devices. In contrast, BIOS navigation is harder since it can only be done via a keyboard.

- Multiple OS support. Whereas BIOS allows a single boot loader, UEFI lets users install loaders for Debian-based Ubuntu and other Linux variants, along with Windows OS loaders, in the same EFI system partition.

- Programming. UEFI firmware is written predominantly in C language, which enables users to add or remove functions with less programming than BIOS, which is written in an assembler language, sometimes in combination with C.

- Security. Secure Boot is a UEFI protocol for Windows 10 or later Windows versions. Secure Boot makes a system's firmware the root of trust to verify device and system integrity, preventing hackers from installing rootkits in the time between bootup and handoff to the OS. Secure Boot also enables an authorized user to configure networks and troubleshoot issues remotely, something a BIOS administrator must be physically present to do.

- Multicast deployment. Device manufacturers can broadcast a PC image to multiple PCs without overwhelming the network or image server.

UEFI disadvantages

Security is one of the biggest concerns with UEFI.

Software is always a target for threat actors, and UEFI is no exception. UEFI implementation flaws may allow threat actors to gain and maintain access to a compromised system, then take advantage of such persistence to install malware. This malware may cause a compromised component in the motherboard or a corrupted PCI to persist, even if the physical hard drive is replaced, creating serious security issues that can only be eliminated by completely replacing the device. By targeting UEFI and its various components (platform initializers, drivers, bootloaders, etc.), cyberattackers may also be able to evade defensive actions such as turning a device on or off or prevent a reinstalled OS from being treated as a clean device (another standard defensive practice).

A well-known malware targeting UEFI is known as BlackLotus. In April 2023, Microsoft released a guidance document to help organizations assess whether they have been compromised by the exploitation of CVE-2022-21894 (BatonDrop) via the BlackLotus UEFI bootkit.

This bootkit writes malicious bootloader files to the ESP and can run at computer startup (before the OS even loads). Consequently, it can interfere with and even deactivate built-in OS security mechanisms. Successful exploitation of the CVE via BlackLotus could allow attackers to take control of an affected system and to maintain persistence in the system.

Real-world attacks on UEFI have been detected recently. One such attack, dubbed TrickBot, surfaced in December 2020. TrickBot malware works by attempting to spy on device firmware, which could permit malicious actors to subvert the boot process and gain access to the OS.

The TrickBot episode came on the heels of 2018 findings by ESET Research, a Slovak outlet for the information security community, which claimed to have discovered a rootkit in the wild that potentially enabled hackers to surveil UEFI firmware and install malicious code.

Aside from security issues, organizations switching to UEFI may incur a cost related to booting from flash. While flash booting is faster than booting from hard disk drives, older systems may require a retrofit, namely a larger flash die on the motherboard to switch to UEFI booting.

Another potential drawback of UEFI is its reliance on the FAT file format, which is maintained by the OS. Larger drive partitions can add too much system overhead, thus defeating some of the performance advantages of UEFI. In this scenario, BIOS can be a more useful option, especially for a computer running an older OS version and smaller boot disks.

How to determine and access UEFI/BIOS settings

To determine whether a computer boots from BIOS or UEFI, press the Windows and R keys on the keyboard to launch the Run configuration box. Type MSInfo32 in the dialog box and hit the Enter key. A system summary screen appears. Look for the entry entitled BIOS Mode, and make note of the corresponding value. If the value says Legacy, the system has BIOS. Otherwise, UEFI will appear in the value field.

Windows users can access UEFI via the PC Settings option in the search bar. The path is PC Settings > Update & Security > Recovery > Advanced Startup, and select the Restart Now option. From the menu, select Troubleshoot > Advanced Options > UEFI Firmware Settings, and restart again.

Linux machines with UEFI installed will show it in the sys/firmware/efi directory. This will also be reflected in the Linux Grand Unified Bootloader boot manager as grub-efi, rather than grub-pc for BIOS.

Coreboot and UEFI

Like UEFI, open source coreboot is another option vying to replace legacy BIOS. Formerly known as LinuxBIOS, coreboot is a flexible firmware for modern computers and embedded systems. The firmware performs a minimal amount of hardware initialization before executing a payload (Linux kernel, FILO, SeaBIOS, etc.). Coreboot can be faster than BIOS and UEFI, with additional benefits of high performance, stability, enhanced security and easier maintenance. Since coreboot is open source, any improvements are shared with all users.

The coreboot project kicked off in 1999. Since then, many people have contributed to its code and it remains a community-based development project, with numerous supporters. Some of its key supporters include Libreboot (blob-free coreboot distribution), Skulls (simple coreboot images for IBM ThinkPad laptops) and MrChromebox (custom coreboot firmware and utilities for Chromebook devices).

Windows 11, now 2 years old, recently added Microsoft Copilot.

Explore the differences between Windows 11 vs. Windows 10 and how to extend Windows 10 support as it approaches end of life. Find out if it's worthwhile to upgrade to Windows 11 right now and how to plan a Windows 11 upgrade project.