Windows Distributed File System (DFS) Namespace primer

This excerpt from "The Complete Guide to Windows Server 2008" goes over the basics of Distributed File System Namespace (DFSN). Learn the applications, components and mechanics of DFSN, as well as what's new with Windows Server 2008.

|

This chapter excerpt from The Complete Guide to Windows Server 2008, by John Savill, is printed with permission from Sams Publishing, Copyright 2008. Click here to purchase the book. |

Think about how users normally access data. Normally, you map a letter to a share on a server as part of a logon script or other policy. If users have to access multiple shares on a server, they have multiple mapped drives, until their Explorer interface looks like a can of alphabet soup. This is not usable. Alternatively, the users may know the Universal Naming Convention (UNC) path of a share (for example, \\<server>\<share>) and use it to access less data that are used relatively infrequently. However, this is difficult for the average user. Finally, users can search for shares by browsing the network, clicking a server, and viewing the shares that are available. Now this browsing of shares is made a little easier by publishing shares in Active Directory (AD), but it's still a flat structure of shares. The more shares you have, the harder it is to find the data you want to find.

DFSN enables you to create a hierarchical namespace for the data that users can navigate. Although DFSN gives the impression of being a single share with a number of folders, it is a series of pointers that redirect the users to the location of data without the users' knowledge. With DFS, the user sees a single share to connect to, which has a hierarchical layout that makes navigation of the data available and intuitive. Think of DFSN as a share virtualization service, with all the shares as virtual names within the namespace.

A DFSN Example

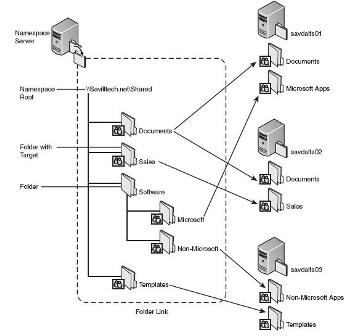

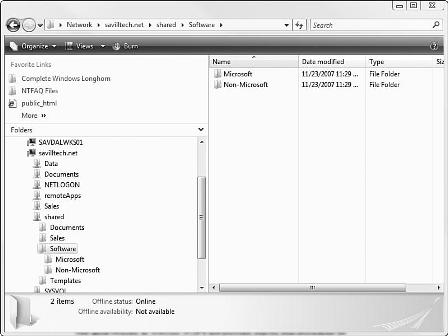

Figure 15-1 shows an example of three file servers with two shares each. Under normal circumstances, users would have six mapped drive letters for each of the shares or a combination of mapped drive letters and the use of UNC paths. Instead, a single share is used, which provides a single view of all the shares that are available but of which the user is unaware. The user thinks she is navigating a single share where all the information resides (see Figure 15-2), which is what the end user sees when viewing a domain-based namespace. The only clue that the user isn't browsing a normal server share is that instead of a server name, there's a domain name (for example, savilltech.net). That is, of course, because the user is viewing a domain-based DFSN. If the user were viewing a stand-alone server namespace, the name of the DFSN server would be used. Notice that the user has no idea where these folders point to; the redirection is all done behind the scenes, unknown to the client.

FIGURE 15-1 An overview of a DFSN. (Click to enlarge)

<<p>FIGURE 15-2 The client view of a DFSN. (Click to enlarge)

It is possible to create multiple namespaces. Doing so may be desirable in environments with different sets of information that are viewed, to avoid showing users large numbers of "folders" that are of no interest to them.

Further Applications of DFSN

This DFSN view simplifies the end user's experience but can also help administrators. Imagine that you want to decommission server savdalfs03 and replace it with savdalfs04. If users are using direct UNC paths to savdalfs03 or mapped drives, after you migrate the data, the users must update any paths containing savdalfs03 to, say, savdafs04, which may include going through many documents that contain embedded links. With DFS, update the folder target to point to savdafs04 instead of savdalfs03, and the end user will never know. Where the information resides does not affect users. The same approach is possible for server consolidation. Let's say you're moving shares that were on three servers down to one server. With DFSN, you just change the folder target; the client never knows.

DFSN Interoperability with NetWare

The preceding section looked at migrating data. You can also use that approach to move data from other OSs, such as NetWare, to Windows. Performing a migration would normally be complex and troublesome. It would involve trying to move the data and update the client paths at the right times. Instead, simply perform the following:

-

- Create a DFSN with folders that have targets on the NetWare OS.

-

- Update all user paths from \\netwareserver\share to the path via DFS. Do this over a period of weeks because the NetWare path and DFS path both work and point to the same location.

-

- When all clients are accessing NetWare via DFS, migrate the contents of a NetWare share to a Windows-based server and update the DFS folder target to point to the Windows server instead of the NetWare server.

With this approach, you don't have to try to make sure all paths that point to NetWare are updated at the time you migrate the actual data. Instead, take your time and update all paths to the DFSN weeks in advance of the actual move. DFS links can point to virtually any file share that the client OS can communicate with. Remember that DFS redirects the user. It does not act as a protocol or communication gateway. DFS has been tested with and used to connect to not only Server Message Block (SMB) shares but also Network File System (NFS) and Distributed Authoring and Versioning (DAV) shares.

DFSN Components and Mechanics

A number of components in DFSN are core to the functionality of DFS. For example, the namespace server is a server with the DFSN service that stores the actual namespace for the DFSN instance. Clients use DFSN servers to navigate and view the logical namespaces. The namespace root is the starting point in a DFSN logical namespace. The actual namespace can be stored in a stand-alone mode, where the namespace is written to the Registry and cached in memory, or in a domain mode, which uses AD to store the namespace, enabling multiple servers to host the namespace, providing greater availability and scalability by spreading the client requests to navigate the namespace across multiple servers.

With DFSN, there are two types of folder: a plain folder and a folder with a target/link. Folder target and folder link are used interchangeably in the OS. Both of these folder types, with or without targets, are created the same way, using the DFS Management MMC snap-in. However, a folder without a target is configured without any links to target shares on other servers and can contain other folders with or without links. You would typically create folders without links for the purpose of adding hierarchy to the namespace—for example, grouping other types of links. The earlier example shows a folder named software that was created with no links, and it contained two subfolders, both with links to Microsoft and non- Microsoft software. A folder with a target has a target share where actual content is stored. You cannot add folders in the DFSN to a folder that has targets. A folder that has targets is considered a boundary point for the DFSN. When a user is redirected to a DFS target, that target share can have a folder hierarchy, but it does not link back to DFS or have other DFS links. It is possible to have folder links pointing to another DFSN. This allows you to create embedded namespaces and large DFS environments.

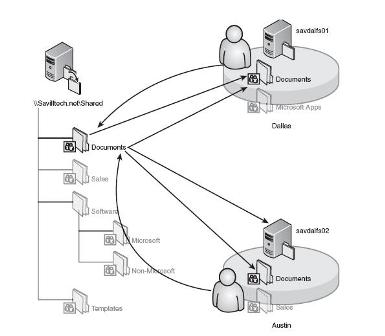

Folder targets can point to any share, and you can point to more than one share for a DFS folder, as is the case with documents in Figure 15-1. Why? Typically, there are two reasons. First, do this to provide redundancy so if one server that hosts the data goes down, clients can be redirected to another folder target that should host the same content. The second reason is to allow regionally distributed environments to host copies of a folder on servers at each location without the clients having to worry about which copy of the data to use. The users are automatically redirected to the folder target that is closest. This is determined by checking the AD site that the client IP address belongs in and the AD sites of the various servers that are folder targets for a specific folder. This process is shown in Figure 15-3. This figure shows the same DFS configuration as Figure 15-1, but now the servers hosting documents are in two different AD sites, and clients in each site are directed to the folder target in their local site. DFS is an AD site-aware application, and this is another reason why getting your AD sites properly defined is vital.

FIGURE 15-3 The site awareness of namespaces. (Click to enlarge)

This single namespace folder that redirects users to a target that is closest to them is useful. Imagine how it could be used in software deployment. Today, when deploying software, you may need to perform checks on where the user is and run a separate script. With DFS, just deploy the software from a DFSN path, and the user automatically downloads and installs the software from the closest folder target.

So what is required for clients to be able to use DFS? Any computer running Windows NT 4.0 with Service Pack 6a or above supports namespaces (with Windows Preinstallation Environment [PE] supporting standalone namespaces only). However, the following OSs also support client failback to a preferred folder target:

-

- Windows Server 2008

-

- Windows Vista Business, Windows Vista Enterprise, Windows Vista Ultimate

-

- Windows Server 2003 Release 2

-

- Windows Storage Server 2003 Release 2

-

- Windows Server 2003 with Service Pack 2, or Service Pack 1 and the Windows Server 2003 client failback hotfix (KB898900)

-

- Windows XP Professional with Service Pack 3 or Service Pack 2 and the Windows XP client failback hotfix (KB898900)

Client failback enables a client who was redirected to another folder target because his preferred target was not available (for example, because the server crashed) to be redirected to the preferred target when the target is available again and the client's referral Time to Live (TTL) has expired, which causes the client to ask the DFS server which folder target it should use.

The configuration of sites is covered in more detail later in this chapter, but for now you at least understand the idea behind DFSN.

Windows Server 2008 DFSN Changes

There are some major differences between the Windows Server 2008 implementation of DFSN and those of previous versions:

-

- Prior to Windows Server 2008, a maximum number of links could exist within a single namespace; this maximum number was 5,000 for a domain-based DFSN and 50,000 for a stand-alone DFSN. Because of this limitation, it was sometimes necessary for companies to chain together multiple namespaces. With Windows Server 2008, there is no limit imposed by DFSN. However, there are still performance issues that may limit the number of links you can have in a namespace, but this will be much higher than the old limits. To avoid the limits, all domain controllers must be running Windows Server 2008 and the domain must be running in Windows Server 2008 mode, which means the new metadata and schema changes must have been propagated into the domain.

-

- In terms of performance, the internal workings of DFS have been improved, providing much better performance than with previous DFS implementations, enabling faster link additions and the DFS server to start faster with large namespaces.

-

- Command-line tools are supplied as part of the DFS role, including dfsutil and dfsdiag, which can be used to completely manage DFS from the command line or scripts.

-

- There is now a single MMC snap-in that manages both DFSN and replication.

-

- Cluster support for stand-alone namespaces now enables a standalone namespace to be made highly available. However, this is possible only on Windows Server 2008 cluster members. For a domainbased namespace, a cluster is not required because the namespace is stored in AD, and high availability is added via multiple DFSN servers configured to read from AD.

These changes do not affect the clients, however, only how you manage the DFS servers.

We have talked about having multiple targets for a DFSN folder. However, there are challenges with this, which is where the second component of DFS—DFSR—comes into play.

| John Savill, BS, MCSE, MS ITP Server Administrator, MS ITP Enterprise Administrator, Clustering MVP, is the Central US manager for EMC's Microsoft technical infrastructure practice and chief Microsoft architect. John has worked in infrastructure solutions for 15 years in different industries and this is his fourth solo book project. John is a speaker at many major technology shows and has spoken at Tech Ed in 2006, 2007, and 2008. |