Applying lean concepts to software testing

If we're going to use a factory analogy for software development, shouldn't we at least study the techniques modern factories use? In this tip, software quality expert Matt Heusser describes concepts used first for lean manufacturing, which are now being applied to software development and software testing.

The term lean manufacturing was created by two Americans, Daniel Womack and James Jones, who codified the counter-intuitive truths used at Toyota into a set of rules. Among those rules: most people can accomplish most jobs, efficiency is less important than effectiveness, and the customer for any step in the process is the consumer of that step.

For software development, this would mean that developers are the customers of business analysts and testers are the customers of developers. In order to process work quickly, the Japanese empowered those customers to specify how the work was to be handed out.

For us, that means a developer could look at a requirements document and explain what sections aren't offering him value, along with what questions he needs answered in order to proceed. Likewise, a tester could do the same with the processes from which the builds are created and delivered.

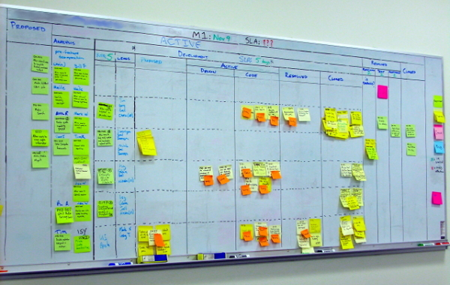

We do this to create something called "flow." If software is flowing, then instead of batching up features for weeks or months and then throwing it at the "next team in the assembly line," we assemble and transfer just one piece at a time. That might be a minimum marketable feature or change. This way everyone has continuous work. We think of excess work in progress inventory as waste, so won't have work "queues" for staff. Instead, staff further down the line pull work forward by asking for it. Some teams visualize this in a sort of kanban board, like the one below setup by consultants at Modus Cooperandi:

Notice with a physical board you can make just as many 'test' boxes as you have testers. When all the boxes are full, the testers can not take on more work. This identifies a bottleneck, but it does more than that: The developer simply can not move more stickies into test. This means the developer can't get his current task off the board; he'll need to either find ways to help the testers, go work on some untracked project, or twiddle his thumbs.

It's that first choice -- finding ways to relieve the bottleneck -- that allows the team to be highly effective.

So there you have it: Lean principles in action. Drive out waste by focusing on value, achieve one-piece flow by the use of pull, and practice continuous improvement. Now let's talk about using it in a software testing, quality or development organization.

"Drive out waste. Great. We can get rid of coffee breaks."

This is certainly a response to the idea of driving out waste, albeit a short-sighted and misguided one. In lean, two groups get to determine what is waste: The customers (waste in product), and the contributors or do-ers, who get to decide what is waste in process.

That might just mean the contributors decide the coffee break is critical to their team morale, but your management-required departmental staff meeting is not. Viewed this way, a fair number of traditional activities, such as a creating status reports, estimates, and process verification steps might be viewed as waste.

In some cases, the process steps may be required by law or an auditor. In that case, we view the work as valuable to someone else; we'll want to do the minimum documentation that could possibly work. In other cases, with things like estimates, we can change the game.

For example, say a team has achieved flow; we break the work down into small chunks and know how long a typical chunk takes to travel through the system. Because we don't have work-in-progress inventory for requirements, management can add a new requirement in the front at any time and expect the result in, say, a week. Because we know about how long it takes to do a 'chunk' and how many 'chunks' we can process in two weeks, management can pick any arbitrary date and we can be sure to deliver something on that date.

It's not that easy to break up a systems integration project. You might have to do some estimating; but even then, flow can help make those estimates meaningful.

Talk to me about testing

Hopefully, some applications of lean testing are clear: Breaking the work down into small features, having testers assigned to one piece at a time, and treating "I'm blocked" as a swear word. You'll also not want to allow staff to "batch" up testing, possibly going so far as to train other disciplines in some of the principles of testing, so they can lend a hand if needed.

Beyond that, let's explore three of the "big" testing jobs: Testing new software as it comes off the build, regression-testing the old features before a new release, and one made much ado about but rarely practiced: Working with the technical staff to ensure the code is of the highest quality before it comes to test.

The first one, testing new features, is familiar. Lean doesn't change the essence of the work, but it changes the emphasis; we get to ask what is slowing us down and how can we eliminate it. For example, if we find the same defects again and again, take a note of it and bring it up at a team retrospective. If you're having a hard time reproducing defects, perhaps it's time to look into a screen recorder like Spectre. If you don't find value in the daily status meeting, bring it up, and suggest a way to fix it. These meetings exist because someone thought they had value; fight for the value for the team.

When we look at regression testing through the lens of lean, we see a "cadence," a standard period of time it takes to put a release into production. The tester's job is to keep that time short without compromising product quality. Perhaps the person paying for the software doesn't care about product quality for certain features. If that's so, we might be able to skip testing of those features.

Or perhaps some features simply never break; they are off in some corner of the application that is never changed. We'd want to start taking a very tough line on these: What are the odds this software will fail? What is the impact if it fails? Can we actually improve by moving away from doing "stable predictable, repeatable" testing into a more risk-managed approach?

(If the answer is no because all kinds of stuff breaks on every build, we need to have a conversation with the whole team and figure out how to fix it, instead of optimizing test at the expense of the whole.)

Over time, it might be possible to actually shrink that regression-test window while adding features. This is not unheard of; in Lean Thinking Womack and Jones cite an American Gasket maker that improved from twenty-one to six-hundred parts created per employee per day using lean methods. You could do it by having the whole team mob on testing, by managing risk, by developing automation, or by finding and eliminating waste in your day-to-day routine.

Where to go for more

The basics of lean are simple: Flow, pull, reduce work in progress and continually improve. Actually doing it is the hard part. If you're hungry to learn more about lean concepts-- to move from "what" to "how"-- Womack and Jones's work The Machine that Changed the World and also Lean Thinking are two great places to start. For a software-directed take on lean, I recommend Mary and Tom Poppendieck's Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit.