4 types of access control

Access management is the gatekeeper, making sure a device or person can gain entry only to the systems or applications to which they have been granted permission.

A sound identity and access management strategy requires the right mix of policies, procedures and technologies. These IAM ingredients are especially important when an organization wants to be successful with zero-trust cybersecurity principles.

A zero-trust architecture takes the opposite approach to legacy perimeter-based security, which essentially trusts every entity once it has been granted access to the network. With zero trust, devices and individuals are continually authenticated, authorized and validated. The goal is to be sure that access to systems and data is limited to only those who need it to perform their specific duties.

Given the distance organizations have moved from walled-off infrastructures to more dynamic and distributed environments, cybersecurity teams face significant risks managing identities.

At the center of effective IAM practices are access control policies.

Types of access control

Organizations have several ways to provide access control. Each has its own advantages and drawbacks.

Popular access control types include the following:

- Role-based access control (RBAC).

- Discretionary access control (DAC).

- Attribute-based access control (ABAC).

- Mandatory access control (MAC).

Each variation handles access control in its own ways. Consider the options carefully before committing or switching to one.

Role-based access control

With RBAC, organizations assign access permissions in accordance with a staff member's job responsibilities. An HR staffer, for example, needs to access records from specific systems and applications that a colleague on the sales team does not require. That employee in sales, meanwhile, needs client information that the HR worker does not.

RBAC aligns the clearly defined job functions of a staff member with the work they do. Permissions are assigned accordingly. Access to adjacent resources is restricted, protecting contiguous systems and applications from access creep.

RBAC is simple to configure and edit. Because the process is easy to automate, the risk of manual administrative errors is lowered. RBAC also scales well, so it is effective for both large and small organizations.

There are clear downsides to RBAC. Staff responsibilities continuously change, which means access rights can be dynamic. Changes in the threat environment may require a faster response than RBAC easily enables. Also, RBAC lacks granularity about which specific data an entity can access.

Discretionary-based control

DAC puts the security administrative power squarely in the hands of a resource's stakeholder. This highly distributed approach enables individual lines of business to grant or restrict entry to an asset without authorization from more centralized management.

DAC relies on access control lists (ACLs), which categorize users based on permissions or set up groups of users that are allowed entry to specific resources.

DAC is often used to provide a verified source with editing access, as with a shared Google Doc or in a Facebook group.

DAC is a quick way to grant access, but it is not the most secure. Its generalized approach to access provides external actors a faster route to the asset than other types of access control.

Attribute-based access control

Organizations will gravitate toward ABAC if their preference is to apply a policy-based approach. The ABAC method allows access to assets according to user characteristics aligned with functions such as department, professional objectives and security clearance.

ABAC applies Boolean logic to build a rubric to demarcate which assets a user can access and the limitations on that access.

ABAC doesn't just consider the end user's role; it also assesses context. Is the user connecting from a secure device and location? Has any aspect of the user's need to request data changed in such a way that their authorization should be altered? Is the timing of the request in accordance with corporate policy and regulatory requirements?

There are many ways ABAC can be put into play in an organization. A marketing executive may be able to make changes to collateral, but a salesperson does not have that same editing access. A professor's ability to see a student's grades and coursework might be limited to the term in which they are teaching that student. A medical professional is allowed access to a patient's file only if they are treating that person and only from a secure location.

The upside to ABAC is it delivers a level of specificity. An IT organization can set rules based on the characteristics of each system element. Security professionals can adjust access rights based on changing scenarios and evolving regulatory requirements.

The same elements that make ABAC so appealing also create some drawbacks. Its granular nature opens the potential for misconfigurations and performance degradations. Setting and maintaining rules for an ABAC system can be complicated and time-consuming. It can also be difficult to track a specific individual's level of privilege.

Mandatory access control

In organizations where there is a tiered security clearance system, MAC systems are useful. MAC systems are popular with government agencies and organizations in industries that require strict control over confidential and sensitive data, such as finance, engineering and healthcare.

Government agencies can set access rules based on a need-to-know basis via strict classifications. In a private sector setting, MAC makes it possible to limit the number of users who have access to consumer data. These restrictions reduce the risk of a breach.

Of all the access control types, MAC systems deliver the highest level of data protection. Data is classified, and security is administered centrally by one entity. These safeguards reduce the likelihood of a data breach, whether accidental or deliberate.

MAC systems, however, are not easy to implement or manage. When colleagues want to share data, a MAC system could impede that collaboration. Administrators need to continuously update system rules when new files are added or an ACL changes. The rigidity of a MAC system means adjustments are difficult to make.

The future of access control

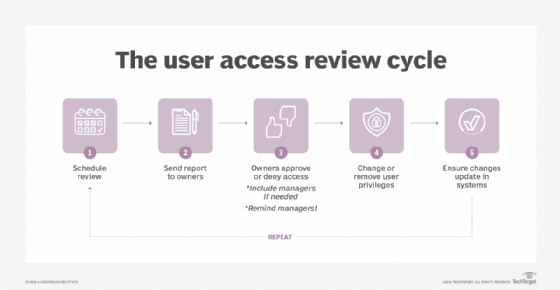

Access management is a continuous process, not just a control over points of entry. On an ongoing basis, organizations need to check the validity of user permissions. This guarantees that staff are in line with things such as the principle of least privilege, which limits access to only what is essential for the individual employee, contractor or device to be productive.

Enterprises need to have controls in place to make policy and permission review an ongoing process -- rather than annually or even less frequently. Staff roles change over time, and rights should be adjusted accordingly. Those adjustments need to be documented -- not just for regulatory compliance purposes, but also for future strategic planning.

Advances in automation help to validate access rights, and they improve overall workflow. Still, organizations need to review these processes, making sure they are an accurate reflection of policy and are executed correctly.

MFA, in which an end-user identity is confirmed through a mobile number, email address or other method, remains an important element in an effective IAM strategy. Even so, it is important for a process to not have too many steps. Security can be a limiting factor to productivity if workers are required to take multiple steps at various stages. Plus, users can find workarounds.

That challenge to balance protection and productivity, along with the lack of flexibility in IAM systems, might be addressed by emerging AI capabilities. AI, for example, could help better separate harmless anomalies from real threats. It could also bring greater context to IAM, helping an organization more dynamically adapt permissions, plan policies and define rules.

Amy Larsen DeCarlo has covered the IT industry for more than 30 years, as a journalist, editor and analyst. As a principal analyst at GlobalData, she covers managed security and cloud services.