Nabugu - stock.adobe.com

Types of DNS servers and how they work, plus security threats

DNS security is a critical component of system administration. Learn about five types of DNS servers, what each does and the security threats each server faces.

The domain name system -- the database that translates easy-to-read and easy-to-use domain names into complex IP addresses -- plays a crucial role in modern networking. Its security is one of the most critical tasks on an administrator's to-do list. Security professionals must understand DNS servers and their role in the network.

This article explains the use and respective security concerns of the following five types of DNS servers:

- DNS authoritative server.

- DNS recursive resolver server.

- DNS stub resolver server.

- DNS caching server.

- DNS forwarding server.

1. DNS authoritative server

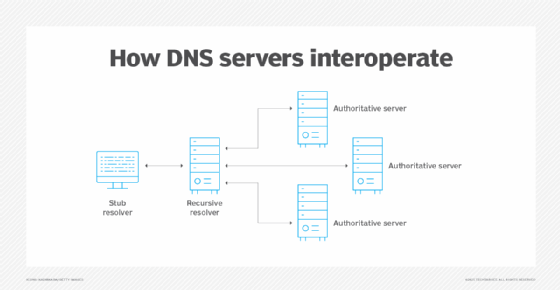

Various DNS servers, including caching and recursive servers, might provide an answer to the name resolution query. Only one DNS server, however, hosts the definitive copy of the resource record containing the name and IP address. This server is the authority on exactly what name relates to what IP address -- hence, the term authoritative server.

Authoritative DNS servers contain the most current and accurate resource records. Some organizations use primary and secondary authoritative servers. Primary DNS servers host read/write copies of resource records, while secondary DNS servers host read-only copies. A single primary DNS server with multiple secondaries increases performance by making several name resolution servers available for queries.

Authoritative DNS servers face availability and authenticity attacks, including the following:

- DDoS attacks that interrupt or delay query responses.

- DNS hijacking that redirects queries to unauthorized DNS servers.

- DNS spoofing that embeds unauthorized information in resource records.

The integrity and security of authoritative DNS servers are of paramount concern to administrators and security professionals.

2. DNS recursive resolver server

Recursive resolver DNS servers provide the intermediate name resolution steps necessary for internet-based DNS services. They handle DNS requests on behalf of client devices, enabling the clients to avoid the heavy burden of resolving names and IP addresses. A single request from a client device could pass through several recursive resolvers before arriving at the authoritative DNS server for a complete answer. This extra work is hidden from the client. ISPs manage most recursive resolvers.

Recursive resolvers face many of the same security challenges as authoritative servers, so their security is equally important. Be aware of the following potential attacks:

- DDoS or similar resource consumption attacks that seek to prevent name resolution.

- DNS spoofing or cache poisoning attacks that seek to inject unauthorized name resolution information.

DNS recursive resolver servers are sometimes called DNS resolvers. Note that they usually cache information, much like DNS caching servers.

3. DNS stub resolver server

DNS stub resolvers are an optional component of a company's name resolution infrastructure, designed to improve name resolution performance. They reside between the clients and dedicated recursive resolvers, simplifying client configuration and enabling performance features, like caching and forwarding.

Stub resolvers offer limited configuration options compared to full DNS recursive resolvers, but these focused settings enable them to fulfill a specific role. They are deployed on servers or other intermediary network appliances.

Typical stub resolver functionality includes the following:

- Forwarding to send queries to the appropriate recursive resolver.

- Caching to temporarily store recent name resolution query results.

- Internal network deployment within large-scale complex networks.

Security threats to stub resolvers typically include misconfiguration, cache poisoning, and availability or resource consumption attacks.

4. DNS caching server

Within types of DNS servers, DNS caching servers reside between authoritative DNS servers and clients to improve name resolution performance. Caching servers check their local caches before sending a lookup to other DNS servers.

These servers don't host the resource records that relate names and IP addresses, however. Rather, they cache or remember the results of name resolution queries that pass through them. Over time, this cache grows, increasing the likelihood that the caching server can satisfy name resolution queries instead of the longer lookup process that queries the authoritative server.

DNS caching server security concerns include ensuring the cache contains accurate information directing clients to legitimate resources -- thus avoiding cache poisoning -- and configuring the servers to query the correct upstream DNS servers. Maintaining short time-to-live values and periodically flushing the cache help secure the server.

5. DNS forwarding server

Forwarding servers typically reside in an organization's DMZ. They receive name resolution queries from the internal DNS servers and forward the queries to external DNS servers on the internet. This configuration avoids internal DNS servers having direct internet connections -- a security risk -- while still ensuring name resolution for websites, email and more. They provide a security benefit and typically enhance network performance.

Note that DNS forwarding servers are also often configured as caching servers to deliver additional performance.

Securing forwarding servers is sometimes more challenging than safeguarding other DNS servers because they connect directly to the internet from the DMZ. Administrators must ensure no connectivity, other than name resolution responses, is possible from the DMZ inward.

DNS client

End-user workstations and non-DNS servers rely on name resolution to let users type easily remembered names and computers to address network packets to IP addresses. These devices have a DNS client integrated into the OS that automatically generates queries and sends them to the configured DNS server.

For example, when a network troubleshooter types the ping www.example.com command to test connectivity, the system's DNS client sends a name resolution request to its configured DNS server, asking for the IP address associated with server42. Once DNS provides the information, the system addresses the ping packets to the provided IP address. The query, however, could pass through stub resolvers and recursive DNS servers and ultimately reach an authoritative server before this information is found.

Note that DNS client software often caches resolved name information, too. View this cache on a Windows computer by opening the terminal and typing ipconfig /displaydns.

Client devices might be vulnerable to cache poisoning attacks, but they typically are merely the victims of attacks against DNS servers aimed at causing the servers to provide inaccurate information.

Learning about name resolution

Understanding the name resolution process enables administrators to secure and troubleshoot DNS issues. It is important to protect all communication paths and servers involved in this process.

Before jumping in, here are a few terms to understand:

- DNS root name server is the first place a recursive server sends a query if it does not have the query answer cached. This server then directs queries to top-level domain (TLD) name servers. Root name servers are indexes of all the servers that have information queried. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers' (ICANN) Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) operates the 13 main DNS root name servers.

- TLDs are the classifiers after the domain name in a URL -- for example, .com in techtarget.com. TLDs help classify and categorize websites based on their purpose or location. Generic TLDs include .com for commerce, .edu for education, .org for organizations and .gov for governments. Country code TLDs include .uk for the United Kingdom and .au for Australia.

- TLD name servers provide DNS recursive resolvers with the IP address for their corresponding domains. ICANN's IANA also manages TLD name servers.

- Resource records are DNS database entries that map a name to an IP address. They are the ultimate targets of the name resolution process, which consists of relating names to IP addresses.

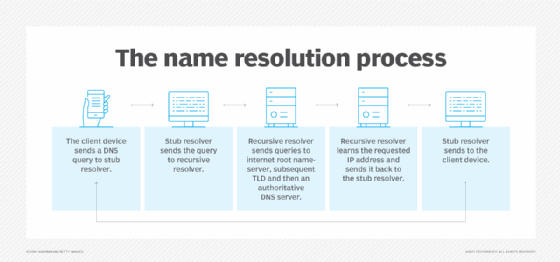

Assuming a query for an internet resource, such as a website, the name resolution process generally looks like this:

- The client device makes a DNS query for an IP address based on a user or application requirement.

- The client device checks its own DNS cache for the information before passing the query to its configured DNS server, which could be a stub resolver.

- The stub resolver sends the query to a recursive resolver, which checks its cache.

- The recursive resolver sends a series of recursive queries to an internet root name server, subsequent TLD and then an authoritative DNS server.

- The recursive resolver learns the requested IP address and passes it back to the stub resolver.

- The stub resolver passes the IP address to the client device.

- The client device uses the IP address to complete the destination IP address field of network packets.

The process can vary if the IP address is already stored in one of the caches or if the resolution is answered earlier in the steps. The above list, however, outlines a general name resolution sequence.

A key capability

Name resolution is one of the most important components of any network deployment, and securing it is critical. That process begins by understanding the various types of DNS servers, their roles and how they fit into the name resolution process. From there, determine which DNS servers reside in your network -- or which you should consider deploying for security and performance. Next, look at the integrity of each server's DNS information, whether cached or stored in the DNS database. Finally, don't forget to examine network connectivity between all DNS components.

Many supplemental DNS security capabilities exist, including DNS Security Extensions, DNS over HTTPS, DNS over TLS, Windows Active Directory-integrated zones and more. Determine whether any of these options can help you secure this critical service.

Use the above information today to start securing your DNS name resolution infrastructure.

Damon Garn owns Cogspinner Coaction and provides freelance IT writing and editing services. He has written multiple CompTIA study guides, including the Linux+, Cloud Essentials+ and Server+ guides, and contributes extensively to Informa TechTarget Editorial, The New Stack and CompTIA Blogs.