Getty Images/iStockphoto

Why Massachusetts' data breach reports are so high

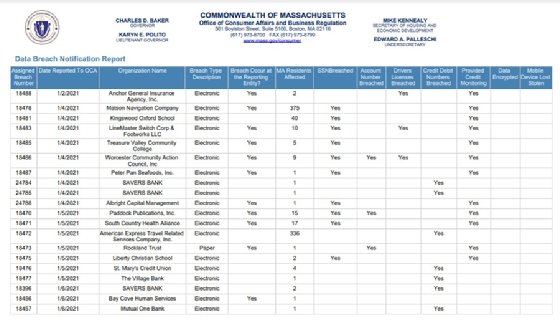

Massachusetts discloses breaches of companies that affect just a single resident, giving the commonwealth a much larger number of 2021 incidents than other states.

In 2021, Massachusetts reported 2,488 data breaches, the most incidents reported to the attorney general in one year since it started recording and disclosing the data in 2007.

Of all the U.S. states that publicly reported their data breach notifications in 2021, that was by far the highest. The next closest state to that mark was New Hampshire, with 1,127 reported data breaches.

That 2,488 figure is not entirely an outlier for Massachusetts, as it has reported over 1,800 annual data breaches in eight of the last nine years, including 2,002 in 2016 and 2,188 in 2020.

There are several explanations as to why these figures seem so high compared to other states. In Massachusetts, every data breach that impacts even one resident of the state must be reported to the director of the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation (OCABR) and the attorney general, while other states set minimum requirements for notifications that the government receives.

California, for example, reported about 300 data security breaches in 2021, but all those breaches listed on the attorney general's website have a minimum required number of California residents that were impacted at 500. About one-third of Massachusetts' breaches impacted just one individual residing in the state.

Another important note about how Massachusetts reports its data breaches is that it includes both electronic and paper breaches, while other states generally report only cyber incidents. Each year, "paper" data breaches account for 150-250 of the incidents that are published by the state.

However, this still leaves a large quantity of electronic breaches that impact the residents of Massachusetts. Overall, the annual number of potential victims of these breaches in Massachusetts is often over 1,000,000, with 2017 getting as high as 3,377,646.

These figures are usually raised by national incidents that impacted many Massachusetts residents, like the 2021 T-Mobile attack (1,044,774 residents) or the 2017 Equifax data breach that exposed the data for 2,982,421 consumers in the state.

While the figures in recent years have been affected by large national breaches and Massachusetts' particular rules on data breach reporting vary from other states' rules, there is a consistent upward trend of reported data breaches impacting the state's residents. But the different regulatory requirements state-to-state present a confusing picture to both consumers and companies impacted by breaches.

Data breach notifications across the country

Overall, the U.S. is at a strange point in terms of how data breaches have to be reported by a company.

All companies must follow the same general practice: If a customer's information is exposed or stolen by an unauthorized individual, the customer must be informed. When they are informed, and who else gets that same notification, however, are entirely up to the state governments of the individual victims.

Heidi Shey, a principal analyst at Forrester Research, told SearchSecurity that while companies may not want to release data breach notifications and may not have to, it can be an important stepping stone in their public reception.

"Breach notifications could really be an opportunity for companies, because oftentimes people just think of it as a legal obligation. They have to do it for compliance, or they're afraid if they don't, they're going to get fined and all of that," Shey said. "But I think if companies sort of take a step back and take a moment to think about understanding do it right, it's really a chance to build customer trust."

However, the cost of data breaches and the notification and reporting process for them can be heavy.

Rita Heimes, general counsel and chief privacy officer for the International Association of Privacy Professionals, said the potential cost of data breach notifications for companies can add up quickly.

"Without question, compliance with different data breach notification laws can be expensive and complicated. It cannot -- should not -- be done without engaging outside counsel," Heimes said. "Many law firms have built relatively efficient systems for evaluating which states' laws are triggered by an information security incident -- including determining whether the incident even qualifies as a breach under a state's particular legal definition. And these systems also help keep up with myriad data breach notification requirements."

Shey also mentioned the support systems that third parties can provide for companies who need to report data breaches but may not be fully prepared to.

"There are service providers that can help do this. Equifax is a breach response service that can do some of this; Kroll is another example; Experian does this as well," Shey said. "These are major service providers that companies would turn to, to help them facilitate that kind of notification. These providers will help stand up a call center for you to field questions. They'll be the ones responsible for doing the actual mailings, the notifications to people as well or set up a website for you. There's different ways to go about it, but services providers come into play."

With large companies that have customer data from multiple states, they may not have to send one state government the same amount of information on a breach that they send another. Depending on the home state of the consumers in question, a company may not have to inform national consumer reporting agencies at all, even if thousands of individuals have potentially had their data stolen.

In Georgia, for example, the only time a company must report a data breach to a national agency or credit bureau is if more than 10,000 Georgians were impacted. If a local bank in Savannah were breached and 9,999 customers had their information stolen, they would be the only ones that the bank would have to tell about it.

On the other side of the data breach notification spectrum are states like Massachusetts, which keep close tabs on data breaches that impact their residents, take note of every reported breach, no matter the scale, and have different qualifications for when national agencies should get involved.

A spokesperson for Massachusetts' OCABR said in a statement to SearchSecurity the office monitors breach submission reports every business day.

"The information on these notification reports is provided by the reporting person or agency when they submit their notice of data breach," the spokesperson said. "Additionally, and pursuant to M.G.L. Chapter 93H, section 3, the Office makes 'available electronic copies of the sample notice sent to consumers on its website and posts such notice within 1 business day upon receipt from the person that experienced a breach of security.'"

Other states similar to Massachusetts, in terms of the number of residents that need to be impacted, are Montana and Maryland, which require all data breaches that impact their residents reported to the state government. Some states, like New York and Maine, require that the attorney general receives all notifications, but there is a minimum requirement to get national consumer reporting agencies involved.

Deadlines and disclosures

When it comes to how soon residents must be notified of a potential information breach, Massachusetts is similar to Georgia, giving the reporting companies a fair amount of leeway. According to Section 3 of Chapter 93H in the Massachusetts state legislature, a company must inform a potential victim "as soon as practicable and without unreasonable delay."

This wording is not unusual; other states like Kansas and Michigan have no set deadline for reporting data breaches, but some states do have set dates and are firm in their stance on it. Vermont, for example, requires a notice to the attorney general within 14 days of discovering a breach and a notice to consumers within 45 days. Texas, Connecticut and Delaware all require a notice within 60 days of discovery, and Florida and Colorado each require it in under 30 days.

No matter the state, residents often aren't informed that they were the victims of a data breach until months after their information was accessed. In one instance in California, seven months passed between the discovery of the breach and the notification to the consumer. Another case in Delaware had a six-month gap between discovery and notification.

Shey saw the delays as a potential result of companies being ill-prepared to notify consumers across states and the differing laws across the U.S.

"They definitely have to plan for [notifying consumers], especially large companies that span across multiple states. So that's why the response after a breach is so important," Shey said. "When you don't plan for this, it's when the event happens that you're scrambling to figure out not just the issue of what was compromised, who might have been affected in terms of your customer base, but then you have to unravel what are your requirements and your obligations to notify, and that can get messy if you haven't done that work beforehand."

The last main difference in how data breach notification laws operate between U.S. states -- and how Massachusetts sticks out -- is what states governments and attorneys general do when they get notices of data breaches.

About one-third of U.S. states disclose each year how many data breaches impacted the residents of their state. Most states provide extensive lists, dating back a few years and outlining the date of the reported attack, which entity was breached and how many residents of the state may have been impacted.

Of the states that provide information on the breaches, just nine (California, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Vermont and Washington) give examples of the notifications sent to victims, providing the public with information about what kind of breach occurred and what companies generally do when these breaches happen.

In Massachusetts, the reports from the attorney general don't present examples of notification letters sent to victims, but the letters are available through OCABR. The attorney general's website promotes that they can be accessed through a public records request, which is not commonly seen across other state websites.

Currently, there is no federal law in place that defines how to report data breaches to consumers or even requires them to be notified at all. It is therefore up to the individual states, which as of Alabama's 2018 vote have all enacted some form of notification requirement when a resident's personal information may be at risk.

While some are more lenient that others, states like California take their citizens' information and security rights very seriously. Under the California Consumer Privacy Act, any resident has the right to know what of their information is being used and how is it being used, and is allowed to ask a company to delete their personal information at any time. Consumers are also told which third-party groups their information is shared with and are allowed to refuse the sale of their information to other companies.

With its laws, California allows its residents to be in control of their own data privacy, be well informed about how their information is being used and be aware of data breaches within the state.

Even though some states are very open about breaches that impact their residents, others allow them to go unnoticed by most of the public.

As long as data breach notification laws stay as varied nationwide as they currently are, U.S. citizens could be under-informed about how their personal data has been impacted as well as the overall rising risk of data breaches in the country.

But a standardized, federal law for data breach notifications and disclosures might not be on the horizon. Shey explained the regulatory environment and public opinion in other regions are much more welcoming to stricter rules than the U.S.

"I think some of this stems from how the U.S. as a whole thinks about privacy and consumer privacy, because compared to a place like Europe, which looks at it as a fundamental right, you have a right to privacy," Shey said. "Whereas I think in the U.S., it's more of this perspective of a trade-off. Because of that, I think there's greater tie into this environment of what is considered a business-friendly type of policy or regulation versus what is about protecting consumers and their privacy."