Getty Images/iStockphoto

Ransomware: Has the U.S. reached a tipping point?

The ransomware problem has grown more severe in recent years due to a growing number of attacks against large organizations and the standardization of double-extortion tactics.

Between the constantly increasing severity of ransomware attacks and the new government attention placed on it, it's clear that the United States has reached a critical juncture in the fight against ransomware.

Just a few years ago, the malware format primarily targeted individuals and demanded sums of a few hundred dollars, and ransomware, for the most part, simply encrypted a victim's files. Now, ransomware regularly targets large enterprises and critical infrastructure, demands typically reach six- and seven-figure sums and ransomware gangs threaten organizations through double-extortion techniques.

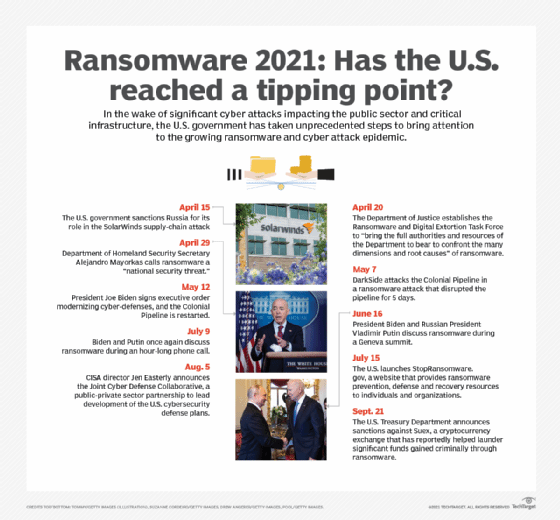

The U.S. government has taken note. Beginning primarily this spring but especially after May's devastating Colonial Pipeline attack, large portions of the federal government have taken action to raise awareness of ransomware, take action against threat actors and ready homeland cyberdefenses.

Matt Hartman, CISA's deputy executive assistant director for cybersecurity, told SearchSecurity that the worsening attacks have pushed the situation to the brink.

"Ransomware is not a new phenomenon, but it has reached a critical tipping point where we have seen it lead directly to real-world consequences," Hartman said. "Ransomware attacks have surged among state, local, tribal and territorial governments, and small and medium businesses. This includes cities, police, hospitals, schools, manufacturing and critical infrastructure targets. And it will continue as long as the business model works for the criminals."

These two occurrences -- the dire state of ransomware and the powers that be seeing it as a national security threat -- raise the question of whether ransomware's moment is a turning point leading to a brighter future or merely the beginning of more dire times.

A worsening situation

In 2020, Emsisoft found that the average ransom demand was $84,000. In another report published in late April, the vendor said that the average ransom payment in 2021 was just over $154,000. One-third of victims paid in 2020, and 27% had paid in 2021 as of April.

Six-figure ransom demands are significant, but recent attacks have seen demands reach sums higher than $50 million. For example, the ransomware gang REvil appeared to demand $50 million from Acer in March; in July, the gang demanded $70 million in its supply-chain ransomware attacks against Kaseya and its customers.

The Sophos 2021 Threat Report released last November noted two reasons for the significant increase of ransomware payments over the years: the rise of "ransomware heavyweights" like REvil attacking enterprise networks, and the now-standard practice of double-extortion tactics. Most threat actors, especially in attacks impacting large organizations, will not just encrypt data but steal and threaten to leak it too.

Other reasons why ransomware has continued to get worse include ransomware as a service and the continuing payment of ransoms -- in part fueled by cyber insurance.

Ransomware as a service (RaaS) refers to the practice of ransomware gangs selling access to tools -- often on a subscription basis -- that allow less-technically-competent threat actors to conduct cyber attacks. Upon the successful receipt of a ransom payment, the gang affiliate receives a portion of the extorted funds. DarkSide and REvil are two high-profile examples of RaaS operations, but there are many others.

Depending on the tools and ransomware service used, RaaS can be utilized for cyber attacks against individuals or networks that require lateral movement.

Param Singh, vice president of Falcon OverWatch at CrowdStrike, said that RaaS is a key reason ransomware is getting worse, as it "brought down the threshold to get into the ransomware business."

"Ransomware is nothing new, but now it has been turned into a business where somebody is providing you access into an environment and the tools to abuse that environment, move laterally, and do all that stuff," he said. "The need for programming capabilities and other things that are required to stitch things together is being brought down lower and lower every year, every month."

As for ransomware payments, U.S. federal government agencies like the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) advise against paying the ransom, as do many security vendors. There are several reasons for this; there's no guarantee that data will be recovered or that a decryption key will work, the victim is funding and emboldening further cybercrime, and downtime will still likely be lengthy and expensive for anyone who is attacked -- whether the ransom is paid or not.

Some ransomware victims utilize cyber insurance policies in order to pay ransoms without as significant a cost. There are signs of this practice slowly changing, however.

Due to the nature of attacks getting worse, and perhaps spurred by recent major attacks, the U.S. has begun to take more direct and indirect action against ransomware.

Government response

On the evening of May 7, the Colonial oil pipeline was disrupted when a ransomware attack credited to DarkSide caused the pipeline to shut down for several days.

A 5,500-mile-long network running from Texas to New Jersey, it supplies approximately half of the East Coast's fuel. The hack created fuel shortages in parts of the United States, as well as significant national attention on the ransomware threat.

That isn't to say ransomware wasn't taken seriously previously; the Department of Justice established the Ransomware and Digital Extortion Task Force a few weeks earlier, and CISA has paid significant attention to the ransomware issue since its establishment in 2018. The Colonial Pipeline situation did, however, appear to signal a ramping up of the government's cyberdefense and ransomware response efforts.

On May 12, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to modernize the country's cyberdefenses.

In June and July, Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin discussed ransomware at length in two separate conversations; the second followed the Kaseya supply-chain ransomware attacks conducted by REvil, which, like DarkSide, has been traced back to Eastern Europe. Russia also has a questionable past in its relationships with ransomware gangs, though the nation denies any involvement in cyber attacks against the United States.

July also saw the launch of StopRansomware.gov, a CISA site providing ransomware-related resources to individuals and organizations.

Most recently, the U.S. Treasury Department last week announced sanctions against the cryptocurrency exchange Suex, which has been accused of laundering significant illicit ransomware funds.

Hartman said the ransomware threat "remains persistent," though he did not provide specifics regarding how much immediate impact recent government activity has had.

"The administration -- from the president on down -- takes this issue very seriously, and we are bringing all our tools to bear," he said. "That being said, the threat of ransomware remains persistent. Malicious actors continue to adjust and evolve their ransomware tactics over time, and we must remain vigilant in maintaining awareness of ransomware attacks and associated tactics, techniques and procedures across the country and around the world."

Ciaran Martin, professor of practice at the University of Oxford's Blavatnik School of Government as well as the first CEO of the U.K.'s National Cyber Security Centre, said that there's no definitive evidence that governments (such as the U.S.) and law enforcement cracking down has had any effect yet, but added that there are potential signs of criminals being more careful.

"There are hints that perhaps some people are being a bit more careful, or at least laying low for a while," he said. "But I don't think there's any evidence yet that systemically we've moved the dial on ransomware. I don't think you can say that yet."

David O'Brien, assistant research director for privacy and security at Harvard University's Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, said that he too has noticed a "pulling back" from some threat actors, though he hasn't seen enough to point to any trend.

"One of these that really stands out to me was at the beginning of the pandemic. I think a couple of groups, a couple of the ransomware gangs, came out and said that they weren't going to target hospitals," O'Brien said. "And then of course, where are we now? We see lots of hospitals being targeted. And even despite the government's ragged rhetoric, which they clearly do at times, it seems like [threat actors] pull back for a little bit and then come right back at it."

Long-term impacts

Two immediate impacts of recent large-scale attacks were the apparent disbanding of DarkSide and the two-month disappearance of REvil. In the former case, any disbanding should be taken with a grain of salt as ransomware gangs commonly disappear and then get rebranded as different gangs soon after; REvil came back earlier this month.

Short-term impacts aside, it's unclear how much recent efforts will curb ransomware activity, if at all. Asked about the primary goal in CISA's fight against ransomware, Hartman put it directly: Stop ransomware attacks impacting U.S. critical infrastructure.

"CISA's top priority, which aligns to that of the Biden-Harris administration, is to put an end to ransomware attacks affecting our nation's critical infrastructure," he said. "As the lead federal cybersecurity agency, CISA can assess and identify malicious cyberactivity by nation-states or criminals. We collect, enrich and share information from the intelligence community, industry and international partners across the broad cybersecurity ecosystem. But we need businesses and other organizations to do their part too. This includes the basics -- keeping systems up to date and installing patches, requiring the use of multifactor authentication and maintaining offline backups of your data."

Martin said that while there's been notable progress in the ransomware fight, it's difficult to say whether the situation will improve before it gets worse.

"It's a pivotal moment, but it's not clear in which direction we will pivot," Martin said. "I think that if you'd asked me, even nine months ago, whether I expected to see ransomware at the top of a U.S./Russia presidential summit agenda, I would have laughed. But the political attention is clearly there. It's not because the problem has gotten worse, although it has, but the consequences of ransomware have become much more visible because they've been much more socially disruptive and much more dangerous."

Martin pointed to attacks on energy grids and hospitals as two examples.

O'Brien agreed that the situation has reached a critical point, in large part because of the vast amounts of money threat actors have made through such attacks.

"It's definitely a pivotal moment. It's the kind of problem that continues to get worse, as I see it. The trajectory has really played out over the last 10 years or so," he said. "What's happened over time is that the cybercriminal networks have become more organized and more sophisticated, and they realize there's actually quite a bit of money to be made in terms of the targets that they focus on. And so now, of course, they're targeting large organizations, they're targeting city governments, they're targeting universities."

Where things are going

Martin saw two possibilities for the coming years.

The first possibility is that ransomware stays at its current level, or slightly less problematic; he compared it to 2019 levels of ransomware where "every so often a wealthy Western corporate executive has a very difficult decision, but pays X million dollars on the quiet and nobody ever hears about it again."

The second possibility is that things get substantially worse before they get better.

"I think there is a chance ransomware has gone from being a largely silent financial harm to being very socially disruptive and potentially very harmful, where it's really disrupting Western healthcare to the point where it's quite obvious people are dying or getting sicker as a result of ransomware," Martin said. "I don't think that's inevitable."

While he acknowledged that the two possibilities may sound alarmist, he said that there's a lining of optimism in option one. If there is stability in ransomware's severity, individuals and organizations can reduce the potency of ransomware attacks by utilizing effective backup strategies, building cyber resilience and learning to cope with threats of publication. That, combined with effective government action and fewer ransoms being paid, could significantly improve the ransomware problem organizations face today.

A French cybersecurity professional and vulnerability researcher who goes by the name x0rz said he expects to see more large targets and more targeted attacks.

"We'll probably see more and more 'mature' targets being hit," he said. "We can already observe some actors moving from an opportunistic approach to a more targeted approach, something we witnessed with the tax companies being specifically targeted in 2021, for instance."

In order to decrease the problem ransomware poses, x0rz argued for a multilayered defense starting at the individual level.

"In three words: Defense in depth. [Utilize] better 'IT hygiene' (good and secure system administration is hard) and patch everything before it's too late," he said. "Also and most importantly: Never pay the ransom. Paying is just fueling ransom operations; it doesn't recover everything and won't prevent the next attack."

Hartman said that where the fight against ransomware goes depends on everyone -- not just the government.

"Where we are in one year or three years is going to depend in large part on how seriously we -- and 'we' includes not just government but businesses and other organizations -- take the threat," he said. "This is a numbers game. The federal government can provide resources and assistance, but every business should recognize the attacks of the last few months as a call to action to strengthen their own cybersecurity defenses and posture and to report incidents to the U.S. government. If we don't strengthen incident reporting and information sharing, the same actors will be able to reuse the same infrastructure and TTPs [tactics, techniques and procedures] to cause significant harm."

In short, the continuing fight against ransomware requires teamwork between the public and private sectors.

"As more organizations report incidents, the more we can do to protect other organizations and other sectors. Collective defense requires all of us," Hartman said. "It requires partnership. And at times, it requires selflessness and a commitment to a more secure cyber-ecosystem."

Alexander Culafi is a writer, journalist and podcaster based in Boston.