adimas - Fotolia

5 ways bad incident response plans can help threat actors

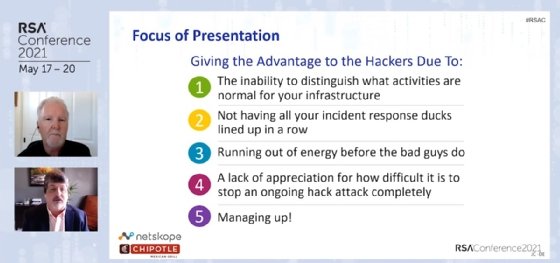

Infosec executives from Netskope and Chipotle Mexican Grill hosted an RSA Conference session about their personal experiences and lessons learned while responding to attacks.

While incident response plans are crucial for enterprises, there are times when they fall short and hinder organizations rather than help.

Real-life attack scenarios were discussed during an RSA Conference 2021 session Monday, where the focus was on mistakes made while executing the plan amid the chaos. James Christiansen, vice president and CSO at Netskope, and David Estlick, CISO at Chipotle Mexican Grill, shared personal stories from incident response (IR) situations they experienced. More importantly, they shared how those experiences revealed what not to do. Some of the lessons learned included keeping a small inner circle during breach response to avoid information leaks, keeping multiple retainers for different IR firms, and having cryptocurrency on hand in case of a ransomware attack.

The session highlighted five main problems overall that contribute to helping the attacker rather than the victim.

The first was the inability to distinguish what activities are normal for your infrastructure. Estlick walked through a real-life scenario that he referred to as "all too common in today's world"-- an organization receives reports of inoperative systems followed by a ransom demand. The problem occurs when systems are taken offline, and the IR team is unable to access them, but payment demands continue to increase.

"We've seen this a lot in news of late," Estlick said during the session.

The solution, according to Estlick, is IR tabletop planning and establishing a clear understanding of assets and a good backup plan that enables recovery if the leadership team decides not to pay the ransom. He emphasized the importance of running through a scenario with the executive team so there is an understanding ahead of time if the organization will pay the ransom or not.

Estlick also recommended running tabletop exercises where the ransom demand is relatively small compared to the business impact so that the executive team can have a meaningful conversation about whether to pay or not, as opposed to dismissing a high, multi-million-dollar ransom that just isn't feasible to pay.

"And if you do pay the ransom, there are some things in preparation -- do you have a Coinbase account? Have you acquired cryptocurrency? These are all things you do not want to be doing under crisis," he said during the session.

Another challenge is determining if the incident worth investigating. Estlick said often times IR teams are virtual and don't have time to track down everything that lands on their desks, so prioritization is crucial.

"Likewise, if they're running down every alert and alarm and you have a high degree of false positives in the system that can lead to complacency," he said. "Make sure you have excess capacity for burst requirements."

Both Estlick and Christiansen said they have multiple companies on retainer because incidents end up coming in groups. "When it hits, it's going to hit hard and there's no way you're going to staff for that type of event. They should know your operating systems and network ahead of time," Christiansen said during the session.

The second problem is not having all your IR ducks in a row. It highlighted another common problem: password security. If there is evidence that admin level passwords have been hacked and the admin password is used on numerous critical systems, then teams need to be prepared to change all admin passwords at a moment's notice.

Estlick shared an anecdote from an incident at a previous employer where he had to reset all credentials at 3 a.m., after several days of an ongoing incident. After going home for a few hours of sleep, he returned to the office expecting the worst professional day of his career. However, he was pleasantly surprised.

"I didn't get anybody coming into my office saying, 'What did you do and why did you do this?' The leadership team was aware the scenario was a possibility and actually shielded me from the pushback in the organization," he said. "Instead, it was if the security deems this necessary, then there is a reason for this. It was all of result of relationships and hard work prior to the incident."

On a related note, the third point in the session was running out of energy before the adversaries do. As Estlick's anecdote captured, incident response teams can be up at all hours of the night. Additionally, timelines for restoration of service and full recovery are unknown. Responding to attacks could take hours, days or weeks.

Christiansen shared an unpleasant experience when one of his own staff was injured on the way home because he fell asleep. "This is learned by experience and making sure you insist on rest," he said during the session. "Key people will want to stay -- they're running on adrenaline."

Estlick said he's seen past examples where critical items such as log data were modified or removed because members of the team were simply exhausted and made mistakes.

The fourth problem they highlighted was a lack of appreciation for how difficult it is to stop an ongoing hack attack completely. Problems can occur when attackers compromise cloud services and the IR teams are not knowledgeable in that area. Thus, it's important to train IR teams to handle the technologies or have expertise on site.

For the final problem, which the speakers called "managing up," Christiansen said executive communication is key. "The reality is, if you're doing a breach analysis, you're going to be delivering a lot of bad news. It's going to be a flow of bad news, so prepare the executive team for this."

Additionally, Christiansen said it's important to show confidence that the situation is under control.

How the IR team is formed is another crucial part to adversary response. Christiansen said it should be made up of key stakeholders, legal, public relations, security team, IT group and customer service who will be part of the notification at the end.

"It's equally important to know what their role isn't -- who isn't going to talk to the press, who's going to talk to executives and internal staff, board members -- it's a key important element," he said. "Getting everyone under attorney-client [privilege] is a way to minimize the impact and stop misinformation from getting out to the public because that can be a huge hit to your branding."

In that regard, Estlick said trying to keep the group as tight as possible is important. In the event that the incident becomes a large-scale, public event, all of those individuals can be deposed. "There's a lot of pressure from people who want to be in the know, but really ask yourself who is critical to be part of that team."