adimas - Fotolia

Timeline of Microsoft Exchange Server attacks raises questions

Multiple security vendors reported that exploitation of the Microsoft Exchange Server zero-days began well before their disclosure, but researchers are at a loss to explain why.

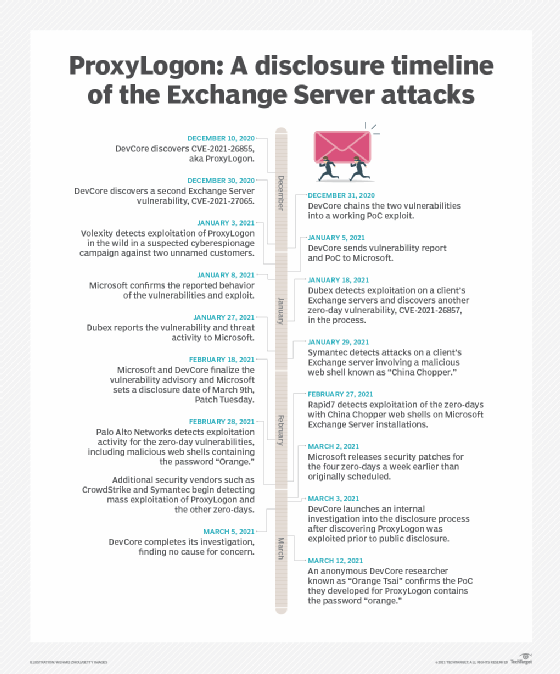

The disclosure timeline of the Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities is stirring questions about potential leaks or breaches that enabled threat actors to exploit the flaws well before Microsoft officially revealed them.

On March 2, the tech giant disclosed that a Chinese nation-state threat group known as Hafnium had exploited four zero-day vulnerabilities to attack on-premises versions of its Exchange Server email software. Microsoft released patches for the four zero-days, but warned that threat actors may have breached organizations prior to the security updates and maintained presence inside their servers through malicious web shells that act as backdoors.

The following day, the Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA) issued an emergency directive urging enterprises to patch because the exploitation "poses an unacceptable risk to Federal Civilian Executive Branch agencies," several news outlets reported that attacks had impacted up to 30,000 U.S. organizations and Microsoft discovered that multiple actors, not just one group like initially thought, were taking advantage of the unpatched systems to attack Exchange servers.

While the vulnerabilities have been patched and Microsoft has released threat detection tools to help mitigate the threat, questions surrounding the disclosure of the vulnerabilities have emerged.

As reports surface that exploitation of the flaws began well before public disclosure, those questions include the possibility of a leak of confidential data that led to a wave of attacks.

Discovery and exploitation

Several researchers and vendors played a role in the disclosure of the major attack on Microsoft's email servers.

The vulnerabilities were first discovered on Dec. 10, 2020, by an anonymous security researcher from Devcore, an infosec consultancy in Taiwan. The researcher, known as Orange Tsai, uncovered the most critical of the four vulnerabilities, CVE-2021-26855, also known as ProxyLogon. The server-side request forgery vulnerability can be used by threat actors to bypass authentication on Exchange servers and impersonate a user.

On Dec. 20, Devcore discovered a second Exchange Server vulnerability, dubbed CVE-2021-27065. Devcore researchers chained the two vulnerabilities into a working proof of concept (PoC) exploit on Dec. 31. While PoC exploits are intended to be used by security teams to demonstrate vulnerabilities and develop mitigations, threat actors can obtain them and use them for attacks. Devcore reported the vulnerabilities and the PoC to Microsoft on Jan. 5, who confirmed receipt the following day.

But earlier this month, after Microsoft had disclosed and patched the flaws, several security vendors reported observing exploitation of the zero-days in January and February. One of those vendors is Volexity, an incident response vendor headquartered in Washington, D.C., that was credited by Microsoft with reporting additional parts of the ProxyLogon attack chain. Initially, Volexity said in a blog post that it observed threat activity in two clients' environments starting on Jan. 6, but later revised the start date to Jan. 3. In an email to SearchSecurity, Matthew Meltzer, security analyst at Volexity, confirmed that the earliest they observed exploitation was on Jan. 3.

"In the initial exploitation, the attackers were very selective with their targeting, with the primary goals being e-mail theft of specific individuals at the targeted organizations," he said.

Dubex, an infosec consultancy based in Denmark, also observed attacks prior to the disclosure date and was similarly credited by Microsoft with helping find additional parts of the attack chain, including CVE-2021-26857, an insecure deserialization vulnerability in Exchange Server's Unified Messaging service (a fourth Exchange Server vulnerability, CVE-2021-26858, was discovered by Microsoft's own Threat Intelligence Center).

In an email to SearchSecurity, Dubex CTO Jacob Herbst said the company saw the first exploitation on a client's Exchange servers on Jan. 18, which led researchers to CVE-2021-26857. "We stopped the attack against our client early, and before any harm was done, but based on the threat actor identified by Microsoft, it was most likely information theft/spying," Herbst said.

Dubex reported the zero-day to Microsoft on Jan. 27. According to Herbst, Dubex believes the attacks were targeted against specific organizations. The exploitation appeared to be limited to a small number of targets.

In mid-February, Microsoft set a disclosure date of March 9, Patch Tuesday, for all four zero-days. However, the date was moved up a week when reports of exploitation began to surge.

Exchange Server exploitation spikes

In late February, other vendors began observing an increase in activity.

Herbst said one possible reason for the increase is that the threat actors most likely found out Microsoft was about to release a fix and then escalated the attacks.

"The reasons could be to cover their tracks by attacking many companies or to ensure persistence to non-hacked organizations that would otherwise be patched. It could also be just to cause chaos," he said. "It could also be state hackers also making money as criminals and ensuring persistence could give them access to deploy crypto miners and ransomware."

Matthieu Faou, malware researcher at ESET, agreed that the news of a patch may have a set a deadline for threat actors. According to Faou, activity increased again just after the patch release -- and expanded beyond Hafnium.

"Attackers were racing against the clock to compromise as many servers as possible before the patches were widely deployed," he said. "Also, at first it appeared that only Hafnium had an exploit for these vulnerabilities. For an unclear reason, multiple other threat groups got access to it at the end of February. It includes well-known APT groups such as Tick, LuckyMouse, Calypso and Winnti Group."

Meltzer also attributed the spike to additional threat groups. "The earlier attacks abused the same vulnerability in Microsoft Exchange, but the mass exploitation that began taking place in late February could very well be the work of different threat actors."

One of the vendors to report on the spike was Rapid7, which on Feb. 27 began to detect a "notable" increase in attacks on Microsoft Exchange Server installations involving a malicious web shell known as "China Chopper," which is popular among Chinese threat actors. China Chopper is often used as a backdoor, meaning that once threat actors place the web shell inside a vulnerable Exchange Server, they can maintain access even after the servers are patched.

"With this foothold, the attacker would then upload and execute tools, often for the purpose of stealing credentials," Rapid7 said in a blog post.

The following day, Palo Alto Networks' Unit 42 threat researchers also detected exploitation activity. The researchers discovered that while most of China Chopper web shells contained alphanumeric passkeys, a few contained the password "Orange."

Unit 42 published its findings in a blog post on March 8. A few days later, Orange Tsai confirmed on Twitter that the PoC they developed for ProxyLogon used a web shell that contained the password "Orange," Devcore's PoC was somehow leaked prior to disclosure and was used in the wild.

As a result, Devcore launched an internal investigation on March 3 into a possible breach or leak that exposed the vulnerabilities and PoC prior to public disclosure. According to Bowen Hsu, Devcore senior project manager, the investigation included all personal computers and devices owned by employees, as well as their internal infrastructure and systems. That investigation concluded on March 5.

"There was no sign that any of those devices and our systems have been hacked. Also, we have investigated our internal systems and found no unusual login attempts or file access," he said in an email to SearchSecurity.

Was there a leak?

Several news outlets, including Bloomberg and the Wall Street Journal, reported that Microsoft launched its own investigation into how the Devcore PoC exploit was leaked prior to the March 2 vulnerability disclosure and patch.

A Microsoft spokesperson confirmed the company is investigating the matter. "We are looking at what might have caused the spike of malicious activity and have not yet drawn any conclusions," the spokesperson said. "We have seen no indications of a leak from Microsoft related to this attack."

Coordinated vulnerability disclosure processes amongst large vendors for widely-used software often involves informing large enterprise and government customers, as well as major technology partners, of critical vulnerabilities prior to their public disclosure in order for those organizations to prepare mitigations.

But partners and customers are typically looped in late in the disclosure process. And while a third party accidentally leaking information about ProxyLogon would explain the Devcore PoC being used in the wild, it wouldn't explain the exploitation of the zero-days in early January.

A blog by ESET also addressed the timeline and pre-disclosure exploitation of the zero-days, noting that in the wild exploitation had started two days before Devcore reported its findings to Microsoft.

"Thus, if these dates are correct, the vulnerabilities were either independently discovered by two different vulnerability research teams or that information about the vulnerabilities was somehow obtained by a malicious entity," the blog post said.

In a blog post on Lawfare, Nicholas Weaver, a security researcher and a professor in the Computer Science department at University of California, Berkeley, suggested that the threat actor had advance knowledge of the vulnerabilities prior to Devcore's discovery.

"Somehow, the threat actor either knew that the exploits would soon become worthless or simply guessed that they would. So, in late February, the attacker changed strategy. Instead of simply exploiting targeted Exchange servers, the attackers stepped up their pace considerably by targeting tens of thousands of servers to install the web shell, an exploit that allows attackers to have remote access to a system," Weaver wrote.

Many questions, few answers

SearchSecurity asked several security vendors about the exploitation of the flaws before the disclosure. One thing they seemingly agreed on: They simply don't know why the attacks started when they did, but it appears to be more than coincidental timing.

"We are not aware of when/why the actors began the attacks," Hsu said, adding that the company is unsure of when its PoC was used in the wild. "However, Devcore found out it is very likely that several zero-day vulnerabilities have been used in the wild in early January 2021."

Similarly, Volexity had no answers about why attacks began in early January following the discovery of ProxyLogon, or why threat activity ramped up as Microsoft prepared to disclose and patch the flaws. "We don't have any direct evidence that explains why exploitation accelerated during the end of February," Meltzer said.

According to Faou, ESET didn't observe anything before Feb. 28 and therefore can't verify other vendors' reports of exploitation in January. "So, we cannot confirm or deny the information. It is likely that the exploit was used in highly targeted attacks at first and not at a large scale, as we've seen in late February and beginning of March."

Satnam Narang, staff research engineer at Tenable, said threat actors typically use zero-days sparingly for targeted attacks so the vulnerabilities aren't widely identified or "burned" before they've had a chance to properly use them and achieve their goals. The increase in ProxyLogon attacks in late February, he said, suggests multiple threat actors had some indication the zero-days were about to be patched.

"It's hard to say for certain, but it's possible the attackers knew the window of opportunity to exploit these zero-days was shortening and this was their last-ditch effort to compromise targets and maintain persistence," Narang said. "This way, they would still have access to organizations' systems even after patches were released and applied."

But the mysteries of why attacks started in early January, and why exploitation suddenly increased in February, remain. Did Hafnium already have these zero-days in its possession, or did the threat group first learn of them from a possible leak in the disclosure process? Could Hafnium have somehow detected that ProxyLogon had been discovered by Devcore researchers? And how did so many other threat groups besides Hafnium learn of the zero-days and begin exploiting them a week before the patches arrived?

For now, experts can only guess. "It is difficult to say definitively just how the threat actors knew their vulnerabilities were burned," Narang said.

News director Rob Wright and news writer Alexander Culafi contributed to this article.