freshidea - Fotolia

Election security threats loom as presidential campaigns begin

Fragile electronic voting systems and the weaponization of social media continue to menace U.S. election systems as presidential candidates ramp up their 2020 campaigns.

Never has it been more important to have a mechanism to audit U.S. voting results, but experts say election security risks combined with the weaponization of social media make the task more difficult than ever.

The electronic voting systems used in a number of states are a concern for security experts who have seen serious flaws in these systems. If the 2020 U.S. election results are disputed by a candidate, there must be a clear way to show voting results are accurate to ensure a peaceful transition of government, said Avi Rubin a computer science professor at Johns Hopkins University, during an RSA Conference 2019 session on election hacking.

Lessons learned in election security

In 2000, a very close election and a confusing voting ballot in Florida led to a drawn out, contested presidential election. Afterward, congress appropriated $4 billion for states to implement electronic voting equipment, and technology vendors were eager to provide those systems.

Rubin became involved in election security in 2003 when he reviewed the Diebold e-voting machine source code. Diebold's voting machine was based on a Windows platform, with a "pretty interface" that allowed voters to use a touchscreen to select candidates, but it "wasn't developed with rigorous software engineering processes," according to Rubin.

In 2003, Rubin was alerted to the fact that Diebold Election System's source code had been accidentally put on an open FTP site. He published a report about the unavoidable security flaws that undermine the election process, just as states such as Maryland were promoting their new, multimillion-dollar electronic voting machines.

"All hell kind of broke loose in Maryland," Rubin said during the RSA conference session. "The problems we found were things like, they were using encryption functions that were already obsolete, they were using them incorrectly and for things they shouldn't have been using them for."

One example is the use of encryption code on contents within the voting machines. "How are you supposed to perform a security analysis of a system if there is encrypted stuff on there?" he said. "They should have been using message authentication codes if they wanted to protect the integrity of things."

Rubin and his research partners also criticized the use of the smartcards that stored all the voting data for each terminal; there was no authentication of smartcards to voting terminals, and the devices weren't encrypted. What's more -- trusted election judges used administration cards to void or alter ballots filed in error by using an easily hackable PIN code, he said.

"We found that the PIN for the administrator that was hard-coded into the software was 1234," Rubin said.

He later became an election judge in Maryland -- without background checks or vetting, according to Rubin -- and learned how simple it would be for a judge to swap out voter cards and shift election results.

"In my hand I had five [smartcards] ... which corresponded to all the votes cast in that precinct," he said. "Because the source code for the Diebold systems had been available online, I knew the format for those ballots. I could have come in with five cards and swapped the ones we actually used with ones in my pocket, and those would have been the results of the election in my precinct."

Basic security for complex problems

There are simple ways individuals and organizations can guard against malicious content. Social media users must authenticate their personal accounts, enable two-factor authentication for all logins, and change passwords at least twice each year. Simple commonsense actions like connecting only with known people and avoiding content from unknown and untrusted sources will also go a long way in keeping fake news from infesting social feeds.

Organizations must take similar steps to protect their social media accounts, with authentication and strong password policies.

Most states, including Maryland, have moved back to paper ballots, which are manually placed into scanners to tally votes. The scanners may have bugs, and manual audits are necessary -- though Rubin said audits aren't performed nearly enough. Without random audits, the scanners may cause problems -- but the method still appears to be a more secure way to conduct voting than with e-voting machines, according to Rubin.

"We are so much better off now because we do have those ballots," he said. "In contested races, we are able to go back and make recounts."

Ronald Rivest, a professor in MIT's Cryptography and Information Security research group, said during a separate session at RSA Conference that "keeping it simple with low-tech paper ballots" is the lesson learned over the past decade. We still need to know that the tabulation of those ballots is accurate, via audits, and states like Colorado and Rhode Island are piloting new risk-limiting audit systems, Rivest said.

However, voting methods vary by state and some states, including battleground states like Pennsylvania, continue to use direct recording electronic systems that produce no paper trails.

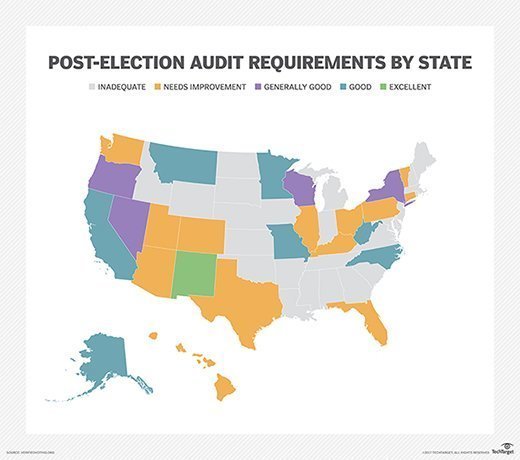

In March 2018, Congress allotted $380 million to help states tighten election security. The funding is to help states acquire more secure voting machines, conduct post-election audits and improve election cybersecurity training.

Weaponization of social media

As critical as it is to ensure voting tallies are accurate, a more insidious election security problem is the amount of misinformation on social platforms that's generated by foreign adversaries to influence the voting public before they ever punch a ballot.

"Forget whether the machine does the right thing; if [the voters] have already been hacked, then [adversaries] have already won the election," Rubin said.

In 2016, 83% of Americans were active on social media and many engaged in politics on social platforms, stating their views on candidates or even their voting plans, said James Foster, CEO of ZeroFox, a social media and digital security company.

More than half of the people in an elective base will engage digitally around a candidate, and that boost in online engagement translates into an increase in vulnerability, he said. Social media has been weaponized, and published reports show over 10,000 Department of Defense (DoD) employees were targeted with Tweets carrying malicious links by nation-state threat actors overseas; once DoD employees clicked on the links, malware was downloaded to their devices, which gave threat actors control of their phones, PCs and social media accounts.

As widespread as disinformation efforts were in 2016, the use of text and images to spread political propaganda were rudimentary compared to the next wave, according to Foster.

"The real scary stuff comes when you start hacking the minds of individuals [with fake news], and that's the stuff that's difficult to put your arms around," Foster said.

Social media took a lot of the blame for the spread of misinformation in 2016, and Facebook and Twitter have been working to improve authenticity, security and reduce misinformation.

But no social platform has determined how to eradicate fake news completely. Meanwhile, the next generation of misinformation isn't merely text or images -- its artificial intelligence-based deepfake videos that make it even more difficult to identify malicious content, Foster said.

"It's going to be very difficult to identify those kinds of fake videos out there, at scale. We know this because it's been very hard to identify [malicious activity] in technology that's much less rich," he said.

Text content -- the simplest kind of media to analyze -- still has a high false positive and negative rate. It's more difficult when OCR has to be used to pull data out of images. Video analysis is even more complex, and exponentially more expensive, Foster explained.

"We will see much bigger issues in 2020," Foster said.