Maksim Kabakou - Fotolia

Congressional websites need to work on TLS

Congressional websites may not always have the best security, according to Joshua Franklin. Although, senators may be better at website security than House representatives.

Joshua Franklin and his father created an election website security research tool, called Election Buster, to study common security failures among congressional websites, as well as fake sites designed to confuse voters.

After investigating election website security in 50 states, five territories and Washington, D.C., Franklin discovered malicious activity and poor website security practices. He discovered that dealing with fake websites may not be very easy, and some members of Congress are not taking advantage of the security measures available to them.

This is part two of a discussion with Joshua Franklin, which took place at DEF CON 26 in Las Vegas last month.

Editor's note: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the most frustrating part of your research into the security of congressional websites?

Joshua Franklin: That was a very interesting, long-drawn-out process. It was very difficult to get in contact with the state election official using your own personal Gmail address and contacting them via email addresses that you have found on their own website -- if they even had email addresses on the website. They might just want you to fill out an [email] form.

I don't want to fill out a form. I want to make sure someone is getting my information. We also found one state that had malware activity inside of their state election website. That was definitely an issue.

Once you find a security issue or fake congressional website, how hard is it to get them fixed or taken down?

Franklin: It does appear to be difficult. You need to work with both your ISP [internet service provider] and the FBI. From our discussion with candidates, that seems to be the most direct way to address that issue. There's not an easy website you can go to.

I believe it would be a fairly long process. When we found the democraticnationalcommittee.org site, I would say it probably took a month to get down. I have no idea if it was a really important issue or not. We don't have a lot of great data on that, unfortunately.

It's very difficult to contact folks to let them know there's some egregious issue on their website or their voter registration system.

If you can't contact these candidates directly about a website issue, is there a way to go through a regional office for the Republican National Committee or Democratic National Committee?

Franklin: Yeah, we've recently made good contacts with the actual parties. And so that is how we are trying to get this addressed, because it's so many people. But that's the best way that we can see to move forward.

Because you already have the contacts, if somebody else finds a flaw in a congressional website, could they contact you?

Franklin: Sure, feel free. You know, we've been working to make the elections secure since 2012, but we can't do everything. That's a small piece of the puzzle.

Have you been focused on congressional website security alone, or have you looked into social media, as well?

Franklin: We have not looked into social media dis- or misinformation. It is something that we've got on the horizon, possibly for 2020.

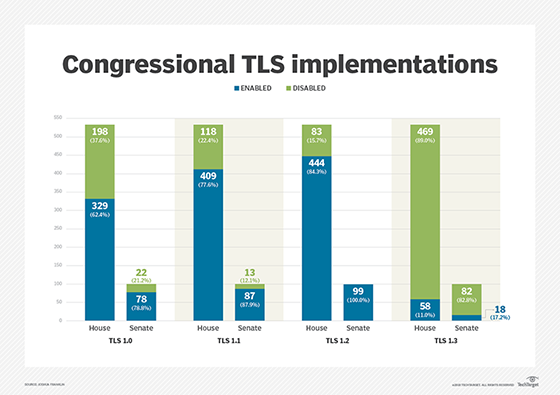

We really wanted to get these measurable stats out on how secure stuff is right now from a TLS [Transport Layer Security] or SSL perspective. Because if something has a really bad TLS implementation, it's an indicator there are probably future issues behind the curtains. So, I wanted to see if we can raise the bar for everyone in that regard.

What else do you plan for the future?

Franklin: We really want to make sure that we are comparing Election Buster information against open source threat intelligence information. [We want to] see if we can get IP addresses that are hosting some of these sites [and] see if they're listed inside some of these threat intelligence feeds as dangerous domains or dangerous IPs. I think that's a really easy thing that could potentially make a difference.

With congressional website security, what should people look out for? What's the aim of threat actors?

Franklin: We think that it's actually the campaigns typosquatting on each other, or two opposing candidates typosquatting on each other. [It's] just purchasing thiscandidatesucks.com, redirecting it to a really bad YouTube video about the other, doing something snarky or funny. But, also, folks tend to take common misspellings of someone's name that is redirected to your site, instead. There [are] a whole host of issues, but those are the primary ones.

There's also another thing that we started looking at are things called homographs, where there's a physical Latin character set that we all use for English, and then there's a Cyrillic character set. There [are] a whole bunch of other character sets, but sometimes characters look very similar. We were really concerned that folks were registering domains like that to confuse voters, but we saw no indication of that.

Other than that, we saw a lot of the states have turned two-letter dot-gov domains -- pa.gov, ga.gov -- they weren't necessarily homographs, even though they showed up in the homograph tool. Because Election Buster wasn't originally looking for this, we hadn't really thought about it, but they were registering pa-gov.com, ga-gov.com.

About half of the states that have voter registration systems have their voter registration system posted not on the dot-gov domain. They actually switch from a dot-gov [top-level domain] to a dot-us or dot-org. We're not exactly sure why. They already have a dot-gov in place, [so] they should use the dot-gov. It is very difficult to get a dot-gov domain, and it really goes a long way to preventing both typosquats and homographs. lt's definitely one of the big recommendations that we have for folks.

I don't get it. There's just going to be some weird configuration issue where someone wasn't able to get a system approved to work in the dot-gov domain or something like that. I know it is difficult to get a dot-gov, but it's worth it; it keeps everyone safe.

We've got some recommendations for campaigns and states to see if we can help make things better. The states that we have gotten in contact with seem to be really concerned about election security; it's definitely not a completely terrible picture that we're painting here about them. Around 20% of those folks need to take a look at their websites.

But those are nowhere near as important as the voter registration systems. If a voter registration system was hacked, it can have a very lasting and bad outcome on the overall election.