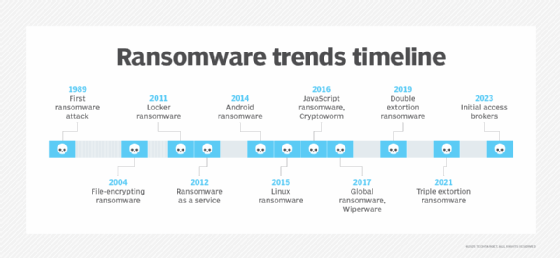

The history and evolution of ransomware attacks

Ransomware creators have become more innovative and savvier as organizations up their defenses.

The headlines are filled with news of the latest ransomware attacks. Individuals and companies continue to fall victim to the crime -- and it's far from a new phenomenon.

From its humble beginnings of malware-laden floppy disks distributed via snail mail, ransomware changed with the tide as the internet and then blockchain and cryptocurrencies took the world by storm.

Cybercriminals' techniques have changed over the years, but the premise remains the same: Attackers target vulnerable victims, block access to something the victims need and demand a ransom to reinstate access.

Let's look at the history and evolution of ransomware to fully understand how it became the ubiquitous cybersecurity threat it is today.

1989: The first ransomware attack

Ransomware has been making its mark for more than 35 years.

Following the World Health Organization's AIDS conference in 1989, Joseph L. Popp, a Harvard-educated biologist, mailed 20,000 floppy disks to event attendees. The packaging suggested the disk contained a questionnaire that could be used to determine the likelihood of someone contracting HIV.

At the time, there was little reason to believe the disks were sent in bad faith. After all, the package came from an accredited researcher -- and no one had ever heard of ransomware before.

After making its way onto victims' systems, the malware, dubbed the AIDS Trojan, used a simple symmetric encryptor to block users from accessing their files. A message appeared on users' screens demanding they mail $189 to a P.O. box in Panama in exchange for access to their files. Due to the simplicity of the virus, IT specialists quickly discovered a decryption key, which enabled victims to regain access without paying the ransom.

Popp probably made little money off the scam -- just consider the cost of shipping 20,000 disks across the globe, along with the hassle of mailing payment to Panama. But his idea eventually developed into a multibillion-dollar industry and caused him to be named the "father of ransomware."

2000-2009: Ransomware returns as the internet booms

Ransomware took a nearly 15-year hiatus after Popp's AIDS Trojan. It reemerged in the early 2000s, as the internet became a household commodity and email became a way of life.

Two of the most notable ransomware attacks at the start of the internet era were GPCode and Archiveus. Unlike much of today's ransomware, cyberthreat actors then focused on quantity over quality, attacking multiple targets and requesting low ransom fees.

2004: GPCode

GPCode infected systems via malicious website links and phishing emails. It used a custom encryption algorithm to encrypt files on Windows systems. The attackers requested as little as $20 for a decryption key. Fortunately for victims, the custom encryption key was fairly straightforward to crack.

2006: Archiveus

Ransomware authors began to understand the importance of strong encryption. Archiveus was the first strain to use an advanced 1,024-bit RSA encryption code. The ransomware authors failed to use different passwords to unlock systems, however. Victims discovered the blunder, and Archiveus fell out of favor.

While GPCode and Archiveus were revolutionary for their time, they are rudimentary by today's standards.

2010-2013: Ransomware goes mainstream

The early 2010s saw the emergence of locker ransomware, stronger encryption algorithms and the newly created concept of cryptocurrencies. This period in the evolution of ransomware was shaped by several variants, including WinLock, Reveton and CryptoLocker.

2011: WinLock -- the first locker ransomware

WinLock was the first locker ransomware, a variant that completely locks victims out of their devices. The nonencrypting malware infected users through malicious websites. Attackers demanded victims send a $10 payment via text message to unlock their PC.

2012: Reveton -- the first RaaS

Reveton was the first ransomware as a service (RaaS) -- a rental service that enables cybercriminals with limited technical skills to purchase ransomware on the dark web. Reveton displayed fraudulent law enforcement messages that accused victims of committing a crime. The attackers threatened victims with jail time if they didn't pay the ransom. Starting with Reveton, the ability to infect victims with ransomware was brought to the masses.

Reveton was also notably one of the first ransomware attacks to demand payment in bitcoin. Cryptocurrencies, which began in 2009, transformed the ransomware game, enabling threat actors and victims to transfer ransom payments easily and anonymously.

2013: CryptoLocker -- ransomware with advanced encryption

The most sophisticated ransomware yet, CryptoLocker was both a locker and crypto variant. It used an advanced 2,048-bit RSA key and propagated as email attachments to seemingly innocuous messages. Also one of the biggest moneymaking variants of its day, the cybercriminals behind CryptoLocker pocketed $27 million in payments within its first two months – clearly in a different league from GPCode's $20 ransom demands.

2014-2016: Ransomware adds platforms

Until the mid-2010s, ransomware predominantly targeted PCs due to Microsoft's popularity and large user base. This changed as threat actors set their sights on mobile, Mac, Linux and JavaScript.

2014: Simplelocker -- the first Android ransomware

Simplelocker became the first ransomware to encrypt files on Android devices. The strain encrypted images, documents and videos on devices' SD cards. This marked a massive shift in the evolution of ransomware because it opened the doors to a new set of victims and attacks.

2015: Linux.Encoder.1 -- the first Linux ransomware

Linux.Encoder.1 was the first ransomware to target Linux devices. The Trojan exploited a flaw in the e-commerce Magento platform and demanded one bitcoin in exchange for the decryption key.

2016: Ransom32 -- the first JavaScript ransomware

Ransom32, a RaaS, was the first variant based entirely on JavaScript. The code's ability to function across all OSes enabled threat actors to cast a wider net.

2016-present: Ransomware goes global as techniques evolve

The past decade of ransomware has brought continued sophistication in attack techniques, as well as the expansion of ransomware attacks to a global level.

2016: Petya -- ransomware targeting MBR and MFT

Petya didn't encrypt individual files, rather it overwrote the master boot record and encrypted the master file table. This locked victims out of their entire hard drives more quickly than other ransomware techniques.

2016: Zcryptor -- the first cryptoworm

Three months later, the world was exposed to Zcryptor, which combined features of ransomware with worms, creating a threat called a cryptoworm or ransomworm. This combination is especially damaging due to its ability to discreetly duplicate itself across an entire system and any networked devices.

2017: WannaCry -- global ransomware

The infamous WannaCry ransomware attack hit hundreds of thousands of machines across more than 150 countries in organizations ranging from banks to healthcare institutions to law enforcement agencies. It is often referred to as the biggest ransomware attack in history. WannaCry -- also a ransomworm strain -- spread via the EternalBlue vulnerability, an exploit leaked from the National Security Agency. To this day, it targets computers using legacy versions of the Server Message Block protocol -- for which Microsoft released a patch in March 2017, two months before the initial WannaCry attack.

2017: Goldeneye -- building new ransomware on old ransomware

This period of ransomware evolution notably ushered in the trend of improving existing ransomware with new variants rather than creating new strains. In 2017, Goldeneye, a variant of Petya and sibling of WannaCry, epitomized this. The authors fixed decryption faults in the ransomware's predecessors to build a stronger, more dangerous strain.

2017: NotPetya -- mainstream wiperware

Petya variant NotPetya emerged in 2017. It encrypted victims' hard drives, like its forerunner, but it also incorporated new wiper features that deleted and destroyed users' files.

2019: Maze -- the introduction of extortion tactics

The Maze RaaS group presented one of the first examples of double extortion ransomware. Attackers encrypted and exfiltrated sensitive data, demanding one ransom for the decryption key and a second ransom for the return of the stolen data.

2021: BlackCat -- the rise of triple extortion ransomware

BlackCat was one of the first high-profile examples of triple extortion ransomware. Along with encryption and data extortion, it used a third technique: adding DDoS components to the attack.

2023: Medusa -- IABs

While active since 2021, Medusa made headlines in 2023 for incorporating the use of initial access brokers. IABs are nefarious actors who sell access to networks and help improve the speed, efficiency and effectiveness of attacks.

The future may be unknown, but what is known is that malicious actors will continue to refine their methods to become more sophisticated, efficient and effective. Malicious hackers' tactics and techniques will mature, and victims will continue to face locked systems, encrypted files and ransom demands. And, as long as attackers continue to make money, attacks will continue to occur.

Sharon Shea is executive editor of Informa TechTarget's SearchSecurity site.

Isabella Harford previously contributed to writing this article.