apinan - Fotolia

Ransomware 'businesses': Does acting legitimate pay off?

Ransomware gangs such as Maze have portrayed themselves almost like penetration testing firms and referred to victims as 'clients.' What's behind this approach?

While ransomware is an act of extortion aimed at separating users and enterprises from their money, some operators -- at least publicly -- appear to look at the relationship between cybercriminal and victim as a kind of business partnership.

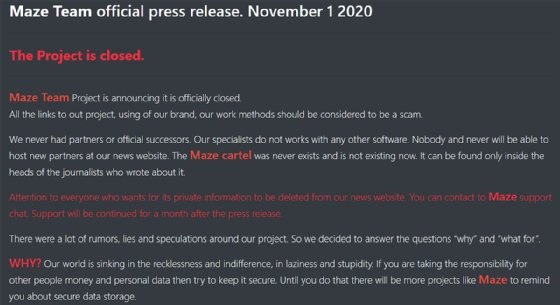

The most prominent example of this can be found with Maze, the recently defunct ransomware gang that pioneered the now-common tactic of not just encrypting data, but also stealing said data and threatening to release it to publicly shame their victims.

One of Maze's signature operating strategies was to portray itself as a kind of infosec services company. Maze would refer to its victims as "partners," its ransomware as a "product," its gang as a "team," and its communications with victims as a kind of "support." The operators published what they called "press releases" that provided updates on its latest attacks and data leaks.

In addition, Maze's communications to victims featured an almost comforting tone as opposed to threats. For example, one ransomware note featured in a McAfee report on Maze earlier this year said "We understand your stress and worry" and "If you have any problems our friendly support team is always here to assist you in a live chat!"

Maze is not the only ransomware operation to conduct business this way; Emsisoft threat analyst Brett Callow pointed to Pysa as an operator doing something similar, and Kaspersky Lab researcher Fedor Sinitsyn cited SunCrypt, MountLocker and Avaddon as those that use wording like "client" to describe victims.

Adam Meyers, senior vice president of intelligence at CrowdStrike, said that the idea of treating ransomware like a business has been present as long as ransomware has. "This has been going on for a long time, ransomware operators going back to even the earliest ransomware in 1989 portray themselves as providing a service. Modern ransomware in many respects emerged from the fake antivirus schemes in the early 2000s continuing this theme of operating a legitimate business," Meyers said.

Sinitsyn agreed, saying that pretending cybercrime is something more legitimate goes back further than Maze.

"Ransomware actors sometimes state in ransom notes that it was not an attack and the files are not held for ransom, but just 'protected' from 'unauthorized third-party access.' Of course, it has nothing to do with reality. Such malware samples had been observed before Maze started using this rhetoric, which makes us believe they are not its 'inventors.' Nowadays, several other ransomware groups stick to this wording," he said.

Ransomware 'clients'

It's unclear why some ransomware gangs have chosen to portray themselves more like penetration testing companies. SearchSecurity reached out to Maze ransomware operators, but they did not respond.

SearchSecurity also reached out to numerous ransomware experts to find out why this tactic was being utilized. No two experts had the same answer.

Meyers called the strategy a tactic to reassure victims of their security, among other things.

"Today, big game hunting adversaries will present the methods they used to get in as a service that helps make victims more secure after they pay the ransom. This is likely part of the complex identity these actors have created for themselves where they try to identify as businesspeople versus criminals; recently one actor even started making charitable contribution in an attempt to create a Robin Hood-type story for themselves," he said.

Callow, meanwhile, said that he suspects it to be a kind of inside joke among a threat actor group, though in this case he referred to Pysa specifically.

"I suspect that certain threat actors refer to their victims as 'clients,' 'customers' or 'partners' simply because they consider it to be humorous. For example, in a leak related to a medical imaging company, the Pysa operators stated, 'If your mom went to examine her mammary glands to our good partners, then we already know everything about her and about many others who used the services of this company.' The terminology obviously isn't intended to make the relationship less adversarial or to convey a sense of professionalism: It's just snark."

Brian Hussey, vice president of cyber threat response at SentinelOne, offered the perspective that the practice of running a crime operation like something more noble comes down to human psychology over anything else.

"Nobody wants to be the 'bad guy' in the story of their lives. In reality, these gangs are stealing hundreds of millions of dollars from their victims, but this is not the story they want portrayed to the world or to their own psyche. Just as Robin Hood was a glorified thief and Ned Kelly was an idolized murderer, these criminal gangs want to build their reputation as securing the digital world through extreme measures, and maybe lining their pockets a bit in the process. They wish to make themselves the hero of the story," Hussey told SearchSecurity. "Of course, the truth is that they are criminals, nothing they do should be perceived as positive in any way. Often, they target hospitals or industrial control systems that could result in significant loss of life. They are heartless and evil in their own right, but that is not their perspective or the story they want the global public to hear."

Karen Sprenger, COO and chief ransomware negotiator at LMG Security in Missoula, Mont., said she's seen ransomware gangs shift toward more professional-looking aspects like customer support portals, references to "clients" rather than victims, and even offering after-breach reports that describe the vulnerabilities and weaknesses used in the attack. But Sprenger said this approach is not an act; many attackers do see their ransomware operations as a business that offers services similar to penetration testing or red teaming. "They take their business models very seriously," she said. "I do think some of these so-called employees of these ransomware gangs believe they are doing a job and that they're helping [victims]."

Sprenger also said the professional approach of threat actors doesn't really improve the likelihood that they'll get paid. "I don't think most people who are infected are aware of that change in approach," she said, because in most cases victims don't have direct contact with the threat actors or "customer support" services. "When the attacker says, "Pay up or we're going to post your data publicly," I think that's one of the reasons we're seeing more and more companies say "Hmmm, I think we might need to pay."

While it's difficult to understand the inner workings of these cybercriminal groups, the reasons offered are not necessarily mutually exclusive. A gang could see themselves as an actual business while operating like one, seeing themselves as heroes in their own story and viewing it as reassurance tactic for victims. There could also be a bit of dark humor on top. Alternatively, it could be any of those aforementioned reasons and none of the others.

Regardless of what the true reasoning may be for viewing ransomware operations as a business, the very real damage caused by ransomware gangs remains. Ransomware payments continue to go up, and ransomware attacks against healthcare organizations doubled between the second and third quarters of 2020.

Security news editor Rob Wright contributed to this report.