How to build an effective IAM architecture

Identity and access management is changing and so must strategies for managing it. Read up on IAM architecture approaches and how to select the best for your organization.

Identity and access management, or IAM -- the discipline of ensuring the right individuals have access to the right things at the right times -- sometimes falls into the category of things that are so foundational to enterprise security that we don't stop to think about them. Like many technologies that have reached a high level of maturity, IAM becomes plumbing; it goes unnoticed until there's a problem. That doesn't mean IT decision-makers should stop paying attention.

To devise the best IAM architecture for specific use cases, an organization must be clear about what it hopes to accomplish. Let's examine the key questions and decisions involved.

3 key steps to selecting an IAM architecture

There are important starting points, including knowing who will be authenticated and why, determining which applications users employ and understanding where those users are located.

As these questions are answered, pay particular attention to these areas:

- SaaS applications hosted outside the enterprise environment.

- Identity requirements for nonhuman actors (e.g., machines, applications and containers), including potentially ephemeral identities.

- Usage that presupposes identities not belonging to the organization.

The process for creating an effective IAM architecture can be broken down into three steps.

Step 1

Security teams should make a list of usage that they anticipate users will interact with, including applications, services, components and other elements. Consolidating this into a list helps validate with others in the organization that usage assumptions are correct. It can also be used as input into the product selection process when evaluating if IAM mechanisms provide the needed capabilities. As you do this and as outlined above, factor in nonhuman identities as well as human ones since you'll want to make sure to address both. Taking action to manage these nonhuman identities is becoming one of the major trends in IAM and cybersecurity.

Step 2

Think through how different environments -- for example, cloud SaaS applications and on-premises applications such as domain login -- will be linked together. There are times when different systems might be needed to accommodate different types of applications and usage. Understanding which other systems exist outside enterprise boundaries is useful because these systems might need to federate in specific ways. For example, Cloud Provider A might enable federation via Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML), while Provider B does so via OpenID Connect. Each of these needs to be accounted for.

Step 3

Consider carefully which specific areas of IAM are most important to the business. The following list of questions will help enterprises evaluate potential vendors and systems:

- Is MFA necessary?

- Do customers and employees need to be supported in the same system?

- Are automated provisioning and deprovisioning required?

- Which standards need to be supported?

That said, there are many IAM architectural elements, approaches and design principles to consider when evaluating the best option for your organization's business needs.

The evolving IAM architecture

From an architectural point of view, the design of most IAM implementations is relatively straightforward at first glance. Complexities only arise when the implications are considered and extended to particular use cases.

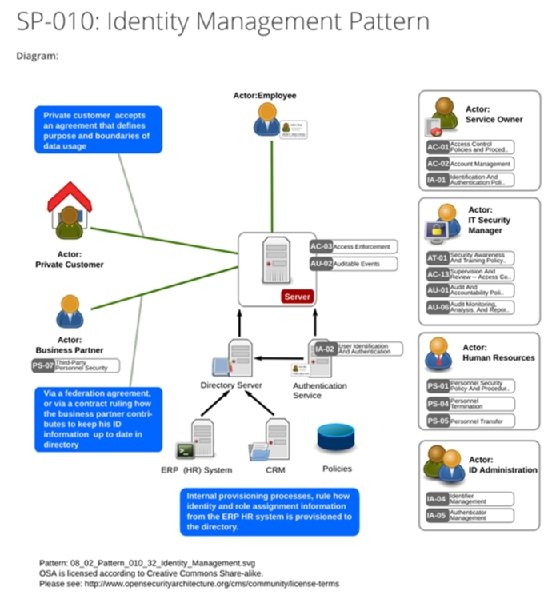

Consider the Open Security Architecture (OSA) design pattern for Identity Management, SP-010 (Figure 1). OSA represents an open, collaborative repository for security architectural design patterns -- i.e., strategies that encapsulate systems in pictorial format for use by the community.

Figure 1 shows the diagram portion of the OSA IAM design pattern. Textual elements, which further explain the conceptual view, description and other salient notes, have been left out for the sake of brevity and because most of these details are implied in the diagram.

A few assumptions are implicit in the diagram. First, it addresses multiple roles that interact with IAM components, as well as systems and services that rely on it. Second, it separates policy enforcement -- in this diagram, enforced at the server/service level -- from policy decisions, which are handled via the combination of the directory and authentication service. Lastly, it is built around the assumption that the organization owns and manages user identity.

This is a traditional design pattern, and it is important to note that some of its underlying assumptions are in transition in a few ways. First, there is the question of federation to external service providers, which can require separate infrastructure to set up and maintain. Then, there is the question of extending identity into the cloud, which, depending on the model employed, can either use state transfer -- for example, SAML or OpenID Connect -- to federate between on-premises and cloud or can use cloud-native identity providers directly.

There is also the question of who is being authenticated and for what purpose. The OSA diagram is clearly targeted at employees. Organizations today must maintain multiple identities beyond their employees, such as customers, application users, system administrative users, machine identities and other types of users. An organization employing a model like this for internal user authentication and access control could very well also have a production application that contains customer user accounts. This might be as sophisticated as a customer IAM platform (CIAM), or depending on the use, it could be as simple as a database table that contains application-specific user credentials.

While descriptive of how IAM has functioned historically, the OSA diagram is likely not particularly descriptive of how most organizations conduct IAM today. This is true because of changes in how IAM is used for employees. Also, it doesn't address customer identities or fully account for technology changes that complicate how IAM operates.

Differences in IAM approaches

If IAM methods are changing and legacy approaches are in a state of transition, how should enterprises select the best approach for their needs? There are a few things to consider:

- What is the organization looking to do?

- What is the scope?

- Where is the source?

It is important to remember that IAM is a huge discipline. It includes several subdisciplines, such as authentication, privileged identity management, authorization and access control, federation, role-based access control (RBAC) and numerous others. There are also multiple different kinds of users, from customers and privileged accounts to service accounts, internal employees, business partners and more.

When selecting IAM architectures, organizations must also consider the intersection points with environments -- and, in particular, sources of identity and identity providers -- that they don't directly control. You'll want to make sure you account for cloud services and third parties, such as business partner environments, identity providers, as-a-service implementations and so on.

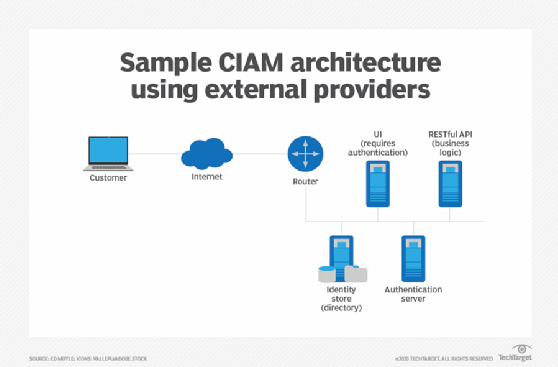

When all this is considered, enterprises might -- and, in fact, very likely will -- end up with a different design than the OSA model presented above. For example, take two completely different models: a CIAM application (i.e., focused on customer identities) versus an internal employee-centric one. The employee-centric one might closely mirror the OSA model. But in a CIAM context, there could be UI components residing at an IaaS provider or implemented in PaaS. There could also be RESTful APIs that implement specific and custom business logic. Within that context, a traditional authentication server and directory (Figure 1) might be employed, or cloud tools, such as an external identity as a service (IDaaS) provider, might be used (Figure 2).

This approach, while using the same logical elements -- directory, policy enforcement points, policy decision points -- as the legacy on-premises model, employs them for a different purpose.

Despite how placid the waters of IAM might seem on the surface though, IAM has become more complicated than it used to be. Consider how innovations affect identity. With cloud transformation, for example, we've seen new IAM strategies emerge, from IDaaS to authentication as a service to native identity systems offered inside cloud environments. Likewise, service-oriented architectures have changed IAM as well, including the creation and rapid adoption of an entirely new authentication state transfer mechanism, OAuth.

Looking ahead, there's more transformation on the horizon. Infrastructure as code is transforming IAM workflows by enabling users to, for example, codify role assignments and IAM policies and permissions. At the same time, Kubernetes is introducing new IAM support structures, such as Kubernetes RBAC and service account management, and requiring adaptation of existing IAM to account for ephemeral instances and other orchestration-specific artifacts. That's just two examples of many; add to the mix continued proliferation of machine identities, passwordless authentication and policy as code, and you have a landscape that is still very much in transition.

Ed Moyle is a technical writer with more than 25 years of experience in information security. He is a partner at SecurityCurve, a consulting, research and education company.