Federal Cloud Computing

In this excerpt from chapter three of Federal Cloud Computing, author Matthew Metheny discusses open source software and its use in the U.S. federal government.

The following is an excerpt from Federal Cloud Computing by author Matthew Metheny and published by Syngress. This section from chapter three explores open source software in the federal government.

Open source software (OSS) and cloud computing are distinctly different concepts that have independently grown in use, both in the public and private sectors, but have each faced adoption challenges by federal agencies. Both OSS and cloud computing individually offer potential benefits for federal agencies to improve their efficiency, agility, and innovation, by enabling them to be more responsive to new or changing requirements in their missions and business operations. OSS improves the way the federal government develops and also distributes software and provides an opportunity to reduce costs through the reuse of existing source code, whereas cloud computing improves the utilization of resources and enables a faster service delivery.

In this chapter, issues faced by OSS in the federal government will be discussed, in addition to the relationship of the federal government's adoption of cloud computing technologies. However, this chapter does not present a differentiation of OSS from proprietary software, rather focuses on highlighting the importance of the federal government's experience with OSS in the adoption of cloud computing.

Over the years, the private sector has encouraged the federal government to consider OSS by making a case that it offers an acceptable alternative to proprietary commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software. Regardless of the potential cost-saving benefits of OSS, federal agencies have historically approached it with cautious interest. Although, there are other potential issues in transitioning from an existing proprietary software, beyond cost. These issues include, a limited in-house skillset for OSS developers within the federal workforce, a lack of knowledge regarding procurement or licensing, and the misinterpretation of acquisition and security policies and guidance. Although some of the challenges and concerns have limited or slowed a broader-scale adoption of OSS, federal agencies have become more familiar with OSS and the marketplace expansion of available products and services, having made considerations for OSS as a viable alternative to enterprise-wide COTS software. This renewed shift to move toward OSS is also being driven by initiatives such as the 18F and the US Digital Service, and the publication of the guidance such as the Digital Services Playbook, which urges federal agencies to "consider using open source, cloud based, and commodity solutions across the technology stack".

Note

Example cases where OSS was identified as a viable option to support federal government programs:

- In May 2011, the US Department of Veterans Affair (VA) CIO stated to avoid costs, and to find a way to involve the private sector in modernizing Veterans Integrated System Technology Architecture (VistA; electronic medical records system), the VA turned to open source. In response, the VA launched the Open Source Electronic Health Record Alliance (OSEHRA) in August 2012 "as a central governing body of a new open source Electronic Health Record (EHR) community".

- In January 2012, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched a new website, the NASA Open Government Initiative, to expand the agency's OSS development. The NASA Open Government co-lead stated: "We believe tomorrow's space and science systems will be built in the open, and that code.nasa.gov will play a big part in getting us there".

Interoperability, portability, and security standards have already been identified as critical barriers for cloud adoption within the federal government. OSS facilitates overcoming standards obstacles through the development and implementation of open standards. OSS communities support standards development through the "shared" development and industry implementation of open standards. In some instances, the federal government's experience with standards development has enabled the acceptance and use of open standards-based, open source technologies and platforms.

Tip

OSS also enables agile software development where the federal agencies can more rapidly deploy technologies and capabilities; however, for agile software development to be viable across the government, supporting government-wide agile acquisition guidance needs to be established. The TechFAR Handbook, consistent with the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), was published to guide federal agencies by explicitly encouraging the use of agile software development and procure development services of modern software development techniques used in the private sector through modular contracting practices.

Many modernization projects have identified the use of OSS as a more economical value for the federal government. Through the use of smaller, agile procurements, federal agencies are achieving a higher yield and greater return on investment (ROI) compared to slower, inefficient long-term investments that use traditional procurement methods that tend to be outpaced by private sector innovations due to lengthy development cycles. Additionally, federal agencies are required to consider multiple factors when defining the overall business case for an Information Technology (IT) investment. Some factors that must be considered as part of the IT investment decision-making process includes the total cost of ownership (TCO) and lifecycle maintenance costs, the costs associated with mitigating security risks, and the security and privacy of data. OSS also requires transitioning to a subscription-based model, thereby reducing the burden for federal agencies to invest in upfront costs, which lock them into capital expenses that may be unrecoverable if the requirements change or a program is canceled or rescoped.

Open source software and the federal government

The federal government's use of OSS has its beginning in the 1990s. During this period, OSS was used primarily within the research and scientific community where collaboration and information sharing was a cultural norm. However, it was not until 2000 that federal agencies began to seriously consider the use of OSS as a model for accelerating innovation within the federal government. As illustrated in Fig. 3.1, the federal government has developed a list of OSS-related studies, policies, and guidelines that have formed the basis for the policy framework that has guided the adoption of OSS. This framework tackles critical issues that have inhibited the federal government from attaining the full benefits offered by OSS. Although gaps still exist in specific guidelines relating to the evaluation, contribution, and sharing of OSS, the policy framework serves as a foundation for guiding federal agencies in the use of OSS. In this section, we will explore the policy framework with the objective of describing how the current policy framework has led to the broader use of OSS across the federal government, and more importantly how this framework has enabled the federal government's adoption of cloud computing by overcoming the challenges with acquisition and security that will be discussed in detail in the next section.

The President's Information Technology Advisory Committee (PITAC), which examined OSS, was given the goal of:

- Charting a vision of how the federal government can support developing OSS;

- Defining a policy framework;

- Identifying policy, legal, and administrative barriers to the widespread adoption of OSS; and

- Identifying potential roles for public institutions in OSS economics model.

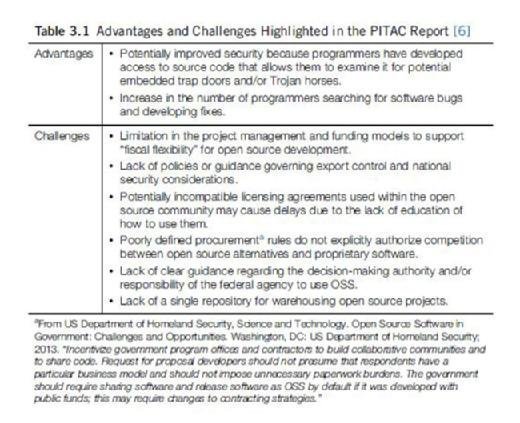

The PITAC published a report concluding that the use of the open source development model (also known as the Bazaar model) was a viable strategy for producing high-quality software through a mixture of public, private, and academic partnerships. In addition, as presented in Table 3.1, the report also highlighted several advantages and challenges. Some of these key issues have been at the forefront of the federal government's adoption of OSS.

Federal Cloud Computing

Author: Matthew Metheny

Learn more about Federal Cloud Computing from publisher Syngress

At checkout, use discount code PBTY25 for 25% off this and other Elsevier titles

Over the years since the PITAC report, the federal government has gained significant experience in both sponsoring and contributing to OSS projects. For example, one of the most widely recognized contributions by the federal government specifically related to security is the Security Enhanced Linux (SELinux) project. The SELinux project focused on improving the Linux kernel through the development of a reference implementation of the Flask security architecture for flexible mandatory access control (MAC). In 2000, the National Security Agency (NSA) made the SELinux available to the Linux community under the terms of the GNU's Not Unix (GNU) General Public License (GPL).

Note

The Open Source Definition (OSD) had its beginning as free software in the early 1980s during the free software movement starting with the GNU project that implemented the GPL. Although the early uses of the terms "open source" and "free software" had been used interchangeably during that period, it was not until 1998 that Netscape Communications Corporation released their Netscape Navigator Web browser source code as Mozilla. At this time, the distinction of the "open source" concept became more mainstream within the broader commercial software industry. The Free Software Foundation and Open Source Initiative (OSI) have similar goals, but there was a notable difference in respect to their philosophies and approved licenses.

Starting in 2001, the MITRE Corporation, for the US Department of Defense (DoD), published a report42 that built a business case for the DoD's use of OSS. The business case discussed both the benefits and risks for considering OSS. In MITRE's conclusion, OSS offered significant benefits to the federal government, such as improved interoperability, increased support for open standards and quality, lower costs, and agility through reduced development time. In addition, MITRE highlighted issues and risks, recommending any consideration of OSS should be carefully reviewed.

Shortly after the MITRE report, the federal government began to establish specific policies and guidance to help clarify issues around OSS. The DoD Chief Information Officer (CIO) published the Department's first official DoD-wide memorandum to reiterate existing policy and to provide clarifying guidance on the acquisition, development, and the use of OSS within the DoD community. Soon after the DoD policy, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) established a memorandum to provide government-wide policy regarding acquisition and licensing issues.

Since 2003, there were multiple misconceptions, specifically within the DoD, regarding the use of OSS. Therefore, in 2007, the US Department of the Navy (DON) CIO released a memorandum that clarified the classification of OSS and directed the Department to identify areas where OSS can be used within the DON's IT portfolio. This was followed by another DoD-wide memorandum in 2009, which provided DoD-wide guidance and clarified the use and development of OSS, including explaining the potential advantages of the DoD reducing the development time for new software, anticipating threats, and response to continual changes in requirements.

In 2009, OMB released the Open Government Directive, which required federal agencies to develop and publish an Open Government Plan on their websites. The Open Government Plan provided a description on how federal agencies would improve transparency and integrate public participation and collaboration. As an example response to the directive support for openness, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), in furtherance of its Open Government Plan, released the "open. NASA" site that was built completely using OSS, such as the LAMP stack and the Wordpress content management system (CMS).

On May 23, 2012, the White House released the Digital Government Strategy that complements other initiatives and established principles for transforming the federal government. More specifically, the strategy outlined the need for a "Shared Platform" approach. In this approach, the federal government would need to leverage "sharing" of resources such as the "use of open source technologies that enable more sharing of data and make content more accessible".

The Second Open Government Action Plan established an action to develop an OSS policy to improve access by federal agencies to custom software to "fuel innovation, lower costs, and benefit the public". In August 2016, the White House published the Federal Source Code Policy, which is consistent with the "Shared Platform" approach in the Digital Government's Strategy, by requiring federal agencies make available custom code as OSS. Further, the policy also made "custom-developed code available for Government-wide reuse and make their code inventories discoverable at https://www.code.gov ('Code.gov')".

Read an excerpt

Download the PDF of chapter 3 in full to learn more!

In this section, we discussed key milestones that have impacted the federal government's cultural acceptance of OSS. It also discussed the current policy framework that has been developed through a series of policies and guidelines to support federal agencies in the adoption of OSS and the establishment of processes and policies to encourage and support the development of OSS. The remainder of this chapter will examine the key issues that have impacted OSS adoption and briefly examine the role of OSS in the adoption of cloud computing within the federal government.

About the author:

Matthew Metheny, PMP, CISSP, CAP, CISA, CSSLP, CRISC, CCSK, is an information security executive and professional with twenty years of experience in the areas of finance management, information technology, information security, risk management, compliance programs, security operations and capabilities, secure software development, security assessment and auditing, security architectures, information security policies/processes, incident response and forensics, and application security and penetration testing. He currently is the Chief Information Security Officer and Director of Cyber Security Operations at the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA), and is responsible for managing CSOSA's enterprise-wide information security and risk management program, and cyber security operations.