Getty Images

Enterprises reluctant to report cyber attacks to authorities

Despite some successful law enforcement operations, including the seizure of a ransom payment, infosec experts say many enterprises are still unlikely to report cyber attacks.

While there has been a recent string of raids, arrests and ransom seizures, they may not be enough to motivate enterprises to work with law enforcement following a cyber attack.

Over the last year, operations involving Europol, the FBI and local authorities across the globe have led to the arrests of a significant number of cybercriminals and an increase in indictments of state-sponsored threat actors.

Earlier this month, the Cyber Police of Ukraine arrested five suspected ransomware affiliates, accused of extorting more than $1 million out of victims in Europe and the U.S. In November, affiliates of REvil ransomware, the variant behind several notable hacks like the supply chain attack against Kaseya, were arrested in an international takedown. One month prior, Europol announced that two suspected members of an unnamed ransomware gang were arrested in Ukraine.

Along with arrests, law enforcement successfully seized a portion of the ransom paid by the Colonial Pipeline Co. following an attack in May. After DarkSide ransomware actors extorted the critical infrastructure company out of $4.4 million, the FBI used a private key to recapture approximately $2.3 million. During a Senate hearing in June, Colonial Pipeline CEO Joseph Blount attributed the swift restoration of pipeline operations to the help of federal authorities.

The increase in law enforcement involvement aligns with the uptick in cyber attacks, many of which go unreported. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) launched a site called "Stop Ransomware" dedicated to reporting attacks that stated, "every ransomware incident should be reported to the U.S. government."

New U.S. government guidelines highlight the increased pressure put on enterprises to disclose attacks, particularly when it comes to paying a ransom, which are primarily paid in cryptocurrency.

To that end, the Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued its first sanctions last year against a virtual currency exchange, Suex. Now, companies that pay may risk breaking the law.

Roger Grimes, data-driven defense evangelist at KnowBe4, told SearchSecurity that it's a challenging point in the history of fighting cybercrime, but he believes CISA is on the right track. Both CISA and the Treasury Department have made it clear they believe it is beneficial to every organization to get authorities involved.

"They have even said that getting any of those entities (CISA, FBI, Secret Service) involved could actually result in reduced liability, because they help you steer clear of OFAC violations, at the very least and offer helpful advice," he said in an email to SearchSecurity.

Why work with law enforcement?

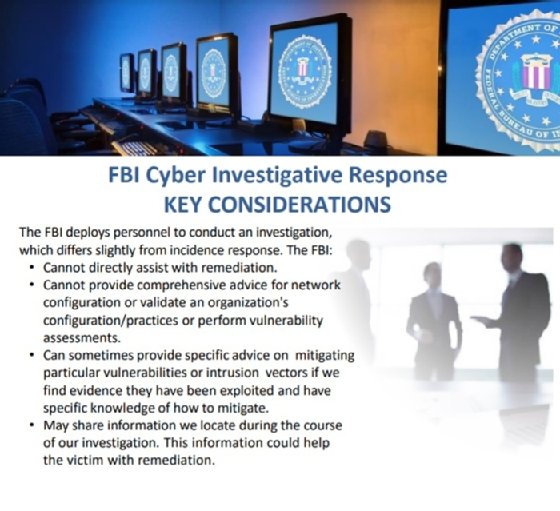

Law enforcement in the Western world is trying to take a more proactive stance in the aftermath of serious cyber attacks, according to Stefano De Blasi, cyberthreat analyst at Digital Shadows. Being included in the incident response process is crucial for law enforcement, he said, in order to gather data on the tactics, techniques and procedures of threat actors, as well as their motivations.

While many incident response plans include notifying law enforcement, infosec experts say the recent successes likely won't factor into the decision whether to work with authorities.

Grimes said that while law enforcement involvement is usually a positive, it does carry the risk that they will take charge of the situation. Organizations never want decisions that impact the company and its stakeholders placed into outside hands, he said, but that is what inviting law enforcement into a scenario can do.

Because involving law enforcement agencies does not usually result in an arrest or retrieval of money, Grimes does not believe senior management or their legal advisors will go out of their way to include them. The decision on involving authorities should not be made by IT, he added.

"Many knowledgeable computer security experts are loath to get law enforcement involved unless it is beneficial or necessary," Grimes said.

A difference in priorities is another deterrent to working with authorities. Stephen Reynolds, a partner at Baker McKenzie who participates in clients' incident response discussions, said that when most companies have a ransomware attack, they just want to get back to business. Questions he's observed during discussions include whether the threat actor will provide a decryptor; if files will be published to data leak sites; if there will be regulatory consequences to making a payment; and company policy and ethics in connection with whether to pay or not.

While many companies are happy to assist law enforcement, Reynolds said their number one priority isn't to catch the bad guy.

"They want to report to law enforcement, but ransomware attacks are very, very crippling on a company and organization. They're really just trying to get their systems back and get back to functioning properly. I think they aren't as motivated to catch the bad guy; that's really law enforcement's bigger priority," Reynolds said.

Another difficulty Reynolds observed is the increased interest in ransomware by multiple U.S. law enforcement entities and other regulatory entities, which can complicate the reporting process and knowing who to report to. One example he cited was from a hearing in November by the House Committee on Oversight and Reform titled, "Cracking Down on Ransomware: Strategies for Disrupting Criminal Hackers and Building Resilience Against Cyber Threat."

During the hearing, Bryan Vorndran, assistant director of the FBI's cyber division, said ransomware incidents often are never reported to the public or law enforcement. According to the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), in 2020 statistics showed a 20% increase in reported ransomware incidents and a 225% increase in reported ransom amounts. Vorndran said that unfortunately, what is reported is only a fraction of the incidents out there.

"Because of the nature of U.S. laws and network infrastructure, we will never know about most malicious activity if it not reported to us by the private sector," Vorndran said during the hearing.

Motivating factors

When it comes down to it, Reynolds said victims reporting typical crimes is pretty normal. However, in the case of cyber attacks it appears additional motivation is needed.

The federal government's recent actions seizing ransom payments offer tangible motivation for many companies, said Beth George, partner in Wilson Sonsini's privacy and cybersecurity practice.

"Frequently, companies wonder if the cost of engaging with law enforcement outweighs the benefits that law enforcement agencies can bring to the table," George said in an email to SearchSecurity.

Companies that are prepared for a ransomware attack, she said, are most likely to engage with law enforcement over those who are caught off guard and scrambling to make last-minute decisions. Enterprises may have developed relationships with the right agencies before an incident even happens, according to George.

Another motivating factor involves the regulatory risks of making a ransom payment to a sanctioned entity such as Suex.

"The OFAC guidance says if you're paying a ransom, one of the mitigating factors is whether you did full cooperation with law enforcement," Reynolds said.

In cases that are not a ransomware attack, communicating with law enforcement is still important, De Blasi said. One example he cited was a cyberespionage campaign. In that case, it would be relevant and useful to involve law enforcement in order to improve understanding of the attack aftermath. It's especially important because companies can suffer multiple attacks.

Cybereason published research last year that showed 80% of victims who paid ransoms were hit again. One example was Toll Group, which was hit twice in three months in 2020. Working with law enforcement on the broader attack surface could potentially help strengthen companies' security posture to be prepared for potential future attacks.

"It's like a cycle. Everything informs the other," De Blasi said.