What is a botnet?

A botnet is a collection of internet-connected devices -- including PCs, servers, mobile devices and internet of things (IoT) devices -- infected and controlled by a common type of malware, often unbeknownst to their owners.

Infected devices are controlled remotely by threat actors, often cybercriminals, and are used for specific functions, yet the malicious operations stay hidden from the user.

Botnets are commonly used to send spam emails, engage in click fraud campaigns and generate malicious traffic for distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

How do botnets work?

The term botnet is derived from the words robot and network. In this case, a bot is a device infected by malicious code, which becomes part of a network, or net, of infected machines controlled by a single attacker or attack group.

A bot is sometimes called a zombie, and a botnet is sometimes referred to as a zombie army. Conversely, those controlling the botnet are sometimes referred to as bot herders.

The botnet malware typically looks for devices with vulnerable endpoints across the internet, rather than targeting specific individuals, companies or industries. The objective of creating a botnet is to infect as many connected devices as possible and use the large-scale computing power and functionality of those devices for automated tasks that generally remain hidden from their users.

For example, an ad fraud botnet infects a user's PC with malicious software that uses the system's web browsers to divert fraudulent traffic to certain online advertisements. However, to stay concealed, the botnet doesn't completely control the operating system or the web browser, which would alert the user. Instead, it uses a small portion of the browser's processes, often running in the background, to send a barely noticeable amount of traffic from the infected device to the targeted ads.

That fraction of bandwidth from an individual device won't offer much to the cybercriminals running the ad fraud campaign. However, a botnet that combines millions of botnet devices can generate massive amounts of fake traffic for ad fraud.

The architecture of a botnet

Botnet infections are usually spread through malware or spyware. Botnet malware is typically designed to automatically scan systems and devices for common vulnerabilities that haven't been patched in hopes of infecting as many devices as possible. Once the desired number of devices is infected, attackers can control the bots using the following two approaches.

The client-server botnet

The traditional client-server model involves setting up a command-and-control (C&C) server and sending automated commands to infected botnet clients through a communications protocol, such as Internet Relay Chat. The bots are often programmed to remain dormant and await commands from the C&C server before initiating malicious activities or cyberattacks.

The P2P botnet

The other approach to controlling infected bots involves a peer-to-peer (P2P) network. Instead of using C&C servers, a P2P botnet relies on a decentralized approach. Infected devices can be programmed to scan for malicious websites or even for other devices that are part of a botnet. The bots can then share updated commands or the latest malware versions.

The P2P approach is more common today as cybercriminals and hacker groups try to avoid detection by cybersecurity vendors and law enforcement agencies. These agencies have often used C&C communications to locate and disrupt botnet operations.

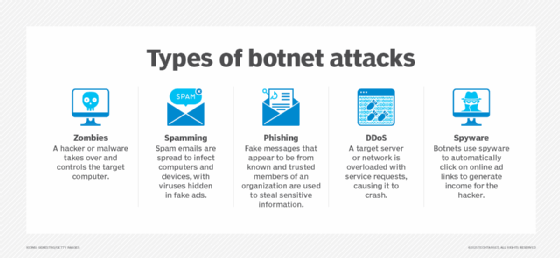

Types of botnet attacks

The different kinds of botnet attacks cover quite a range and include the following:

- Zombies. In this attack, a target computer comes under the control of either a hacker or controlling malware, possibly including an installed Trojan horse. The computer proceeds to execute the processes it's instructed to do.

- Spamming. This attack spreads spam emails to infect other computers and devices, hiding viruses in fake advertisements.

- Phishing. A form of spamming attack, phishing uses fake messages from known and trusted members of an organization to steal sensitive information.

- DDoS. This classic attack overloads a server with a deluge of service requests, causing it to crash.

- Spyware. Botnets that use spyware typically click online advertising links to generate income for the hacker.

Addressing vulnerabilities of IoT devices

The increasing number of connected devices used across modern industries provides an ideal landscape for botnet propagation. Botnets rely on an extensive network of devices to complete their objective, making IoT a prime target with its large attack surface. Today's inexpensive, internet-capable devices are vulnerable to botnet attacks because of their proliferation and because they often have limited security features. In addition, IoT devices are often easier to hack because they can't be managed, accessed or monitored like conventional IT devices. Businesses can work to improve IoT security by putting stricter authentication methods in place.

Disrupting botnet attacks

In the past, botnet attacks were disrupted by focusing on the C&C source. Law enforcement agencies and security vendors traced the bots' communications to wherever the control server was hosted, forcing the hosting or service provider to shut down the server.

However, as botnet malware becomes more sophisticated and communications are decentralized, takedown efforts have shifted away from targeting C&C infrastructures to other approaches. These include identifying and removing botnet malware infections at the source device, identifying and replicating P2P communication methods, and cracking down on monetary transactions rather than technical infrastructure in cases of ad fraud.

How to protect against botnets

There is no one-size-fits-all fix for botnet detection and prevention, but manufacturers and enterprises can start by incorporating the following security controls:

- Implement strong user authentication methods. Develop good security practices such as using two-factor user authentication in addition to complex passwords.

- Secure remote firmware updates. Permit only firmware from the original manufacturer. Hackers can use fake firmware to take control of devices. Put policies in place to ensure that firmware is validated before installation.

- Update software systems regularly. Apply software updates promptly, as they often include security patches and enhancements. Keep antivirus software up to date.

- Be wary of email attachments. Malicious email attachments can often put the hacker just a click away from their target. Only download essential attachments and verify the sender beforehand.

- Monitor the network for unusual activity. By measuring and recording traffic in peripheral networks, abnormal use patterns can be identified, possibly detecting attacks as they begin.

- Investigate failed log-in attempts. Repeated log-in attempts often indicate an attack. Learn to monitor log-in attempts and flag excessive attempts to detect them.

- Use advanced behavioral analysis to detect unusual IoT traffic behavior. By measuring and recording traffic in peripheral networks, abnormal use patterns can be detected, possibly detecting attacks as they begin.

- Automate protective measures in IoT networks. Use machine learning and artificial intelligence to automate protective measures in IoT networks before botnets can cause serious harm.

These measures occur at the manufacturing and enterprise levels, requiring security to be baked into IoT devices from conception and businesses to acknowledge the risks.

From a user perspective, botnet attacks are difficult to detect because devices act normally even when infected. A user might be able to remove the malware, but it's unlikely they will affect the botnet.

Examples of botnet attacks

Bots have been wreaking havoc since the 1990s. One of the first attacks occurred in 1996, when Panix, a NY-based internet service provider (ISP), was knocked offline for several days by a SYN flood attack. This DDoS attack overwhelmed the ISP's servers, preventing them from processing.

Other notable examples of botnet attacks include the following.

Zeus

The Zeus malware, first detected in 2007, is one of the best-known and most widely used malware types in the history of information security. Zeus uses a Trojan horse program to infect vulnerable devices. Variants of this malware have been used for various purposes over the years, including to spread CryptoLocker ransomware.

Initially, Zeus, or Zbot, was used to harvest banking credentials and financial information from users of infected devices. Once the data was collected, attackers used the bots to send out spam and phishing emails that spread the Zeus Trojan to more prospective victims.

In 2009, cybersecurity vendor Damballa estimated Zeus had infected 3.6 million hosts. The following year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) identified a group of Eastern European cybercriminals suspected of being behind the Zeus malware campaign.

The Zeus botnet was repeatedly disrupted in 2010 when two ISPs hosting the C&C servers for Zeus were shut down. However, new versions of the Zeus malware were later discovered.

Cutwail

Cutwail, first detected in 2007, generated 51 million emails per minute -- 45% of the world's total spam at that time. At its zenith, Cutwail penetrated 1.5 million to 2 million computer systems, spewing out 74 billion spam emails per day. It targeted Microsoft Windows systems, using Trojan horse malware that converted infected servers into spambots.

GameOver Zeus

Instead of relying on traditional, centralized C&C servers to control bots, GameOver Zeus, created in 2011, used a P2P network approach, initially making the botnet harder for law enforcement and security vendors to pinpoint and disrupt.

Infected bots communicated using a domain generation algorithm. The GameOver Zeus botnet generated domain names to serve as communication points for infected bots. An infected device randomly selected domains until it reached an active domain that could issue new commands. Security firm Bitdefender found it could issue as many as 10,000 new domains daily.

In 2014, international law enforcement agencies participated in Operation Tovar to temporarily disrupt GameOver Zeus by identifying the domains used by cybercriminals and redirecting bot traffic to government-controlled servers.

The FBI also offered a $3 million reward for Russian hacker Evgeniy Bogachev, who was accused of being the mastermind behind the GameOver Zeus botnet. Bogachev is still at large, and new variants of GameOver Zeus have since emerged.

Methbot

In 2016, cybersecurity services company White Ops revealed an extensive cybercrime operation and ad fraud botnet known as Methbot.

According to security researchers, Methbot generated between $3 million and $5 million in fraudulent ad revenue daily by producing fraudulent clicks for online ads and fake views of video advertisements.

Instead of infecting random devices, the Methbot campaign was run on approximately 800 to 1,200 dedicated servers in data centers in the U.S. and the Netherlands. The campaign's operational infrastructure included 6,000 spoofed domains and more than 850,000 dedicated IP addresses, many of which were falsely registered as belonging to legitimate internet service providers.

The infected servers produced fake clicks and mouse movements and forged Facebook and LinkedIn social media accounts to appear as legitimate users to fool conventional ad fraud detection techniques.

To disrupt Methbot's monetization scheme, White Ops published a list of spoofed domains and fraudulent IP addresses to alert advertisers and enable them to block the addresses.

Mirai

Several powerful, record-setting DDoS attacks were observed in late 2016 and later traced to a brand of malware known as Mirai.

The traffic produced by the DDoS attack came from various connected devices, including wireless routers and closed-circuit television cameras. Mirai malware was designed to scan the internet for unsecured devices while also avoiding IP addresses belonging to major corporations and government agencies. After identifying an unsecured device, the malware attempted to log in using common default passwords. If necessary, the malware resorted to brute-force attacks to guess passwords.

Once a device was compromised, it connected to C&C infrastructure and could divert varying amounts of traffic toward a DDoS target. Devices that were infected often still continued functioning normally, making it challenging to detect Mirai botnet activity.

The Mirai source code was later released to the public, enabling anyone to use the malware to create botnets by targeting poorly protected IoT devices.

Kraken

In 2022, the Kraken botnet achieved one of the highest-ever levels of proliferation, infecting 10% of all Fortune 500 companies with a spyware attack that deployed nearly half a million bots. Each bot could generate 600,000 emails a day. It was also one of the earliest botnets capable of evading detection.

From a user perspective, botnet attacks are challenging to detect because devices act normally even when infected. As botnet and IoT attacks increase in sophistication, IoT security must be addressed at an industry level.

Ransomware, another type of malware, continues to be a major threat to organizations worldwide. Learn what industries and organizations were hit the hardest by ransomware in 2024.