What is the WannaCry ransomware attack?

WannaCry ransomware is a cyberattack that spread by exploiting vulnerabilities in earlier and unpatched versions of the Windows operating system (OS). At its peak in May 2017, WannaCry became a global threat. Cybercriminals used the ransomware to hold organizations' data hostage and extort money in the form of cryptocurrency.

WannaCry spread using EternalBlue, an exploit leaked from the National Security Agency (NSA). EternalBlue enabled attackers to use a zero-day vulnerability to gain access to a system. It targeted Windows computers that used a legacy version of the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol.

WannaCry is one of the first examples of a worldwide ransomware attack. It began with a cyberattack on May 12, 2017, affecting hundreds of thousands of computers in as many as 150 countries.

WannaCry ransomware was particularly dangerous because it propagated through a worm. This meant it could spread automatically without victim participation, which is necessary with ransomware variants that spread through phishing or other social engineering methods.

What is known about WannaCry?

The EternalBlue exploit, initially developed by the NSA, was stolen and leaked about a month before the WannaCry attack by a hacker group called The Shadow Brokers (TSB).

TSB surfaced in 2016 when it began releasing exploit code from the NSA. In April 2017, TSB released EternalBlue to the public, claiming they stole it and other exploits and cyberweapons from the NSA-linked Equation Group.

Although Microsoft had issued a patch for the vulnerability in March 2017 -- a month before it was disclosed by TSB -- many organizations failed to update their Windows systems, exposing them to the WannaCry cryptoworm.

EternalBlue used a vulnerability found only in SMB version 1, which was superseded by newer and more secure versions. Any Windows system that accepted SMBv1 requests was at risk of the exploit. Only systems with versions of SMB enabled or that blocked SMBv1 packets from public networks resisted infection by WannaCry. For example, beginning with Windows 10 and Windows Server 2019, the SMBv1 client is no longer installed by default.

After WannaCry began to spread across computer networks in May 2017, some experts suggested the worm carrying the ransomware might have been released prematurely due to the lack of a functional system for decrypting victim systems after paying the ransom.

Security researchers tentatively linked the WannaCry ransomware worm to the Lazarus Group, a nation-state advanced persistent threat group with ties to the North Korean government. In December 2017, the White House officially attributed the WannaCry attacks to North Korea.

Due to early reports indicating the threat actors behind the ransomware were not providing decryption keys to victims who paid the ransom, many of those attacked chose not to pay. A day after the attack surfaced, security researcher Marcus Hutchins discovered a kill switch that stopped WannaCry from spreading.

How does WannaCry work?

WannaCry encrypted files on Windows devices' hard drives so that users could not access them. In May 2017, the cryptoworm demanded a ransom payment of between $300 and $600 in bitcoin within three days to decrypt the files. However, even after paying, only a handful of victims received decryption keys.

WannaCry exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft's SMBv1 network resource-sharing protocol. The exploit let an attacker transmit crafted packets to any system that accepted data from the public internet on port 445 -- the port reserved for SMB. SMBv1 is a deprecated network protocol.

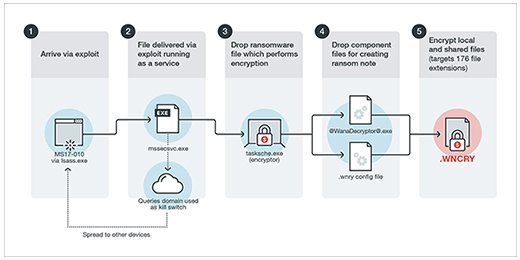

WannaCry appeared on computers as a dropper, a small helper program that delivered and installed malware. The dropper's components included an application for data encryption and decryption, files of encryption keys and a copy of Tor for command-and-control communications.

WannaCry used the EternalBlue exploit to spread. The first step attackers took was to search the target network for devices accepting traffic on TCP port 445, which indicated the system was configured to run SMB. This was generally done by conducting a port scan. Next, attackers initiated an SMBv1 connection to the device. After the connection was made, a buffer overflow was used to take control of the targeted system and install the ransomware component of the attack.

Once a system was affected, the WannaCry worm propagated itself, infecting other unpatched devices -- all without any human interaction.

Even after victims paid the ransom, the ransomware didn't automatically release their computers and decrypt their files, according to security researchers. Rather, victims had to wait and hope that WannaCry's developers would deliver decryption keys for the hostage computers remotely over the internet -- a completely manual process that contained a significant flaw: The hackers didn't have any way to prove who paid the ransom. Since there was only a slight chance the victims would get their files decrypted, the wiser choice was to save their money and rebuild the affected systems, according to security experts.

What was the impact of WannaCry?

WannaCry caused significant financial consequences, as well as extreme inconvenience for businesses across the globe.

The initial May 2017 attack is estimated to have hit more than 230,000 devices. Innumerable devices have fallen victim since. More than 150 countries were affected by the attack, including England, India, Russia, Taiwan and Ukraine. Organizations across many different industries were also infected by the attack, including those in the automotive, emergency, healthcare provider, security and telecom sectors. For example, hospital equipment and ambulances were affected by the attack.

Estimates of the initial WannaCry attack's total financial impact were generally in the hundreds of millions of dollars, though Symantec estimated the total costs at $4 billion. However, what surprised experts about this attack was how little damage it did compared to what it could have done, given its worm functionality.

In the wake of the WannaCry attack, the U.S. Congress introduced the Protecting Our Ability to Counter Hacking Act in May 2017. The act proposed that an independent board review software or hardware vulnerabilities in the government's possession. The act never passed.

WannaCry proved to be a wake-up call for the enterprise cybersecurity world to implement better security programs and renew its focus on the importance of patching. Many security teams have since better educated themselves and their IT departments to protect their organizations against ransomware. According to the Security Intelligence blog run by IBM Security, the chief information security officer role has also seen an upsurge in prominence.

Stopping the spread of WannaCry

Windows released an initial patch well before the initial attack in 2017. Many users, however, did not update their systems in time and were thus vulnerable to the attack.

One day after the initial attack, Microsoft released a security update for its legacy products, including Windows 8, Windows Server 2003 and Windows XP, to fix the vulnerability. Organizations were advised to patch their Windows systems to avoid being hit by the attack.

WannaCry used a kill switch technique to determine whether the malware should encrypt a targeted system. Hardcoded into the malware was a web domain that WannaCry checked for the presence of a live webpage when it first ran. If attempting to access the kill switch and the domain did not result in a live webpage, the malware encrypted the system.

Hutchins discovered he could activate the kill switch by registering a web domain and posting a page on it. Originally, he wanted to track the spread of the ransomware through the domain it was contacting, but he soon found that registering the domain stopped the spread of the infection.

Other security researchers reported the same findings as Hutchins and said new ransomware infections appeared to have slowed since the kill switch was activated.

In August 2017, after a two-year investigation and just months after he stopped the spread of WannaCry and was publicly identified, Hutchins was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He was accused of helping create and spread the Kronos banking Trojan, malware that recorded and exfiltrated user credentials and personally identifiable information from protected computers. In 2019, Hutchins pled guilty to two of the 10 charges he faced but was spared a jail sentence. Instead, he served a one-year supervised release and was allowed to return to the U.K.

Is WannaCry still a threat?

Although the original WannaCry attack is no longer functional, newer variants can exploit the EternalBlue vulnerability, affecting unpatched and unprotected systems. Windows 10's built-in automatic update feature blocks WannaCry, and Windows 11 includes a feature that protects computers from ransomware. Microsoft also made the SMB patch available for Windows XP and older OSes.

With WannaCry also came the concept of the ransomworm and cryptoworm -- code that spreads using remote office services, cloud networks and network endpoints. A ransomworm only needs one entry point to infect an entire network. It then self-propagates to spread to other devices and systems.

Since the initial WannaCry attack, more sophisticated variations of the ransomworm have emerged. These new variants are moving away from traditional ransomware attacks that must have constant communication back to their controllers and replacing them with automated, self-learning methods.

Malware writers have been extremely successful in exploiting Microsoft's SMB protocol. EternalBlue was also a key component of the destructive June 2017 NotPetya ransomware attacks.

The exploit was also used by the Russian-linked Fancy Bear cyberespionage group, also known as Sednit, APT28 or Sofacy, to attack Wi-Fi networks in European hotels in 2017. The exploit has been identified as one of the spreading mechanisms for malicious cryptocurrency miners.

How to defend against WannaCry

Although the initial WannaCry ransomware is no longer functional, it helped inspire the recent surge in ransomware attacks. According to Verizon's "2025 Data Breach Investigations Report," 44% of cybersecurity breaches in 2024 involved ransomware.

Since its release in 1984, SMBv1 has been updated several times; newer versions, such as SMBv2 and SMBv3, operate over port 445, making them potential targets for attackers. If possible, organizations should block external traffic on port 445 using firewalls.

Beyond that, organizations can defend against other ransomware variants by doing the following:

- Setting up secure backup procedures that can be used even if the network is disabled.

- Backing up data regularly using methods like the 3-2-1 backup strategy.

- Educating users on the dangers of phishing, weak passwords and other methods that could lead to ransomware attacks.

- Using antivirus programs with ransomware protection features.

- Keeping software, antimalware and firewall software up to date.

- Using complex passwords and changing them periodically.

- Not clicking on suspicious links or attachments.

- Implementing zero-trust frameworks.

- Improving access management frameworks.

- Implementing incident response strategies.

- Investing in cybersecurity tools that can continually monitor and protect networks from vulnerabilities and attacks.

Ransomware can be removed manually, though this process is not recommended for less skilled users. However, users can remove malware using various tools, including Microsoft Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool and most other antimalware software.

Importance of education against malware attacks

Education plays an important role in defending against malware attacks. It helps organizations and individual employees identify potential threats and suspicious activities, enabling them to avoid putting themselves or their organizations at risk.

Proper training on how to avoid and prevent malware attacks should include how the different types of malware -- such as viruses, ransomware, worms, Trojans, etc. -- work, while also teaching how to recognize attacks based on social engineering and phishing attempts. Relevant parties should also be taught how to properly use anti-malware software and how to adhere to other security procedures.

Even though Hutchins discovered how to stop the initial threat, WannaCry still persisted after the fact. Learn how WannaCry ransomware continued to spread up to two years after the initial infection.