What is a rootkit?

A rootkit is a program or a collection of malicious software tools that give a threat actor remote access to and control over a computer or other system. Although this type of software has some legitimate uses, such as providing remote end-user support, most rootkits open a backdoor on victims' systems to introduce malicious software -- including computer viruses, ransomware, keylogger programs or other types of malware -- or to use the system for further network security attacks.

Rootkits often attempt to prevent the detection of malicious software by deactivating endpoint antimalware and antivirus software. They can be purchased on the dark web and installed during phishing attacks or used as a social engineering tactic to trick users into giving them permission to install them on their systems. This often gives remote cybercriminals administrator access to the system.

Once installed, a rootkit gives the remote actor access to and control over almost every aspect of the operating system (OS). Older antivirus programs often struggled to detect rootkits, but today, most antimalware programs can scan for and remove rootkits hiding within a system.

How rootkits work

Since rootkits can't spread by themselves, they depend on clandestine methods to infect computers. When unsuspecting users give rootkit installer programs permission to be installed on their systems, the rootkits install and conceal themselves until hackers activate them. Rootkits contain malicious tools, including banking credential stealers, password stealers, keyloggers, antivirus disablers and bots for distributed denial-of-service attacks.

Rootkits are installed through the same common vectors as any malicious software, including email phishing campaigns, executable malicious files, crafted malicious PDF files and Microsoft Word documents. They are also connected to compromised shared drives or downloaded software infected with the rootkit from risky websites.

What can be compromised during a rootkit attack?

A rootkit attack can have the following consequences:

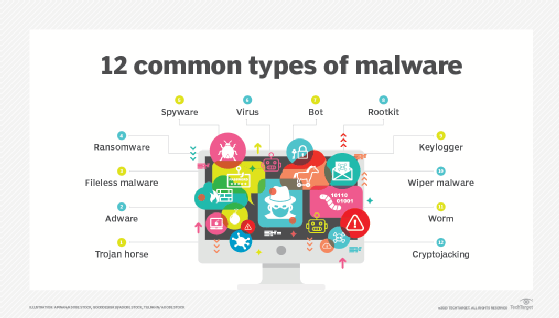

- Causes a malware infection. A rootkit can install malicious software on a computer, system or network that contains viruses, Trojan horses, worms, ransomware, spyware, adware and other deleterious software that compromise system or device performance or the privacy of its information.

- Removes files. Rootkits install themselves through a backdoor into a system, network or device. This can happen during login or result from a security or OS software vulnerability. Once in, the rootkit can automatically execute software that steals or deletes files.

- Intercepts personal information. Payload rootkits often use keyloggers, which capture keystrokes without a user's consent. In other cases, these rootkits issue spam emails that install the rootkits when users open the emails. In both cases, the rootkit steals personal information, such as credit card numbers and online banking data, that is passed on to cybercriminals.

- Steals sensitive data. By entering systems, networks and computers, rootkits can install malware that seeks sensitive proprietary information, usually with the goal of monetizing that data or passing it on to unauthorized sources. Keyloggers, screen scrapers, spyware, adware, backdoors and bots are all methods that rootkits use to steal sensitive data.

- Changes system configurations. Once inside a system, network or computer, a rootkit can modify system configurations. It can establish a stealth mode that makes detection by standard security software difficult. Rootkits can also create a persistent state of presence that makes it difficult or impossible to shut them down, even with a system reboot. A rootkit can provide an attacker with ongoing access or change security authorization privileges to facilitate access.

Symptoms of rootkit infection

A primary goal of a rootkit is to avoid detection to remain installed and accessible on the victim's system. Although rootkit developers aim to keep their malware undetectable, and there aren't many easily identifiable symptoms that flag a rootkit infection, the following are four indicators that a system has been compromised:

- Antimalware stops running. An antimalware application that stops running for no apparent reason might indicate an active rootkit infection.

- Windows settings change by themselves. If Windows settings change without any apparent action by the user, the cause might be a rootkit infection. Other unusual behaviors, such as background images changing or disappearing in the lock screen or pinned items changing on the taskbar, could also indicate a rootkit infection.

- Performance issues. Unusually slow performance, high central processing unit usage and browser redirects might also indicate a rootkit infection.

- Computer lockups. These occur when users can't access their computer or the computer fails to respond to input from a mouse or keyboard.

Types of rootkits

Rootkits are classified based on how they infect, operate or persist on the target system:

- Kernel mode rootkit. This type of rootkit is designed to change the functionality of an OS. The rootkit typically adds its own code -- and, sometimes, its own data structures -- to parts of the OS core, known as the kernel. Many kernel mode rootkits exploit the fact that OSes allow device drivers or loadable modules to execute with the same system privileges as the OS kernel, so the rootkits are packaged as device drivers or modules to avoid detection by antivirus software.

- User mode rootkit. Also known as an application rootkit, a user mode rootkit executes in the same way as an ordinary user program. User mode rootkits can be initialized like other ordinary programs during system startup or injected into the system by a dropper. The method depends on the OS. For example, a Windows rootkit typically focuses on manipulating the basic functionality of Windows dynamic link library files, but in a Unix system, the rootkit might replace an entire application.

- Bootkit or bootloader rootkit. This type of rootkit infects the Master Boot Record of a hard drive or other storage device connected to the target system. Bootkits can subvert the boot process and maintain control over the system after booting. As a result, they have been used successfully to attack systems that use full disk encryption.

- Firmware rootkit. This takes advantage of software embedded in system firmware and installs itself in firmware images used by network cards, basic input/output systems, routers, or other peripherals or devices.

- Memory rootkit. Most rootkit infections can persist in systems for long periods because they install themselves on permanent system storage devices, but memory rootkits load themselves into computer memory or RAM. Memory rootkits persist only until the system RAM is cleared, usually after the computer is restarted.

- Virtualized rootkit. These rootkits are malware that executes as a hypervisor controlling one or many virtual machines (VMs). Rootkits operate differently in a hypervisor-VM environment than on a physical machine. In a VM environment, the VMs controlled by the primary hypervisor machine appear to function normally without noticeable degradation to service or performance on the VMs linked to the hypervisor. This enables the rootkit to do its malicious work with less chance of being detected since all VMs linked to the hypervisor appear to function normally.

Tips for preventing a rootkit attack

Although it's difficult to detect a rootkit attack, an organization can build its defense strategy in the following ways:

- Use strong antivirus and antimalware software. Typically, rootkit detection requires specific add-ons to antimalware packages or special-purpose anti-rootkit scanner software.

- Keep software up to date. Rootkit users continually probe OSes and other systems for security vulnerabilities. OS and system software vendors are aware of this, so whenever they discover vulnerabilities in their products, they immediately issue a security update to eliminate them. As a best practice, IT should immediately update software whenever a new release is issued.

- Monitor the network. Network monitoring and observability software can alert IT immediately if there is an unusually high level of activity at any point along the network, if network nodes suddenly start going offline or if there is any other sign of network activity that can be construed as an anomaly.

- Analyze behavior. Companies that develop strong security permission policies and continually monitor for compliance can reduce the threat of rootkits. For example, if a user who normally accesses a system during the daytime in San Jose, Calif., shows up suddenly as an active user in Europe during nighttime hours, a threat alert could be sent to IT for investigation.

- Enable secure boot. The secure boot features, enabled in BIOS/UEFI settings, can prevent unauthorized operating systems or modified bootleggers from loading.

- Add kernel and hardware rootkit protection. Kernel integrity checks can be implemented to foil a hacker's prediction of the location of kernel code; KASLR (Kernel Address Space Layout Randomization) is an example. Hardware tools such as the Trusted Platform Module (Intel) and Secure Processor (AMD) are detection options that make it harder for rootkits to hide.

- Implement cybersecurity training. Training employees and users in best security practices is always wise but is essential in the case of rootkits, which are often spread through malicious attachments or social engineering attacks.

Rootkit detection and removal

Once a rootkit compromises a system, the potential for malicious activity is high, but organizations can take steps to remediate a compromised system.

Rootkit removal can be difficult, especially for rootkits incorporated into OS kernels, firmware or storage device boot sectors. While some anti-rootkit software can detect and remove some rootkits, this type of malware can be difficult to remove entirely.

One approach to rootkit removal is to reinstall the OS, which, in many cases, eliminates the infection. Removing bootloader rootkits might require accessing the infected storage device using a clean system running a secure OS.

Rebooting a system infected with a memory rootkit removes the infection, but further work might be required to eliminate the source of the infection, which could be linked to command-and-control servers with a presence in the local network or on the public internet.

It's important to remind employees and users to notify IT whenever any laptop, tablet or other device is rootkit-infected.

Examples of rootkit attacks

The following illustrates several notable rootkit attacks:

Gamer attacks targeting Microsoft digital signature. In 2023, a China-based hacking team initiated a campaign that targeted gamers in that country using a rootkit with a valid Microsoft digital signature. The attack allowed it to load into game devices without being blocked and to download unsigned kernel mode drivers directly into memory. The rootkit was able to shut down Windows Defender in target systems.

Spicy Hot Pot attack. In 2020, an incident involving Zirconium, a Chinese advanced persistent threat group that developed a set of rootkit-like functions to infiltrate and compromise targeted systems via social engineering and spear phishing. The group, associated with the Chinese government, employed its custom malware to gain unauthorized access to networks in pursuit of sensitive information.

The Sony BMG copy protection scandal. Perhaps the best-known rootkit incident happened in 2005 when it was discovered that Sony BMG had secretly deployed rootkits on over 25 million CDs that installed digital rights management software on consumer devices to modify their OSes to interfere with CD copying. This also created vulnerabilities to other forms of malware. One program spied on users' private listening habits. The resulting public outcry triggered government investigations, class-action lawsuits and a large recall of the affected CDs.

Wiperware is a newer threat with far worse consequences than phishing and ransomware combined. Learn how to protect your organization from this malicious cybersecurity threat.