What is the difference between WLAN and Wi-Fi?

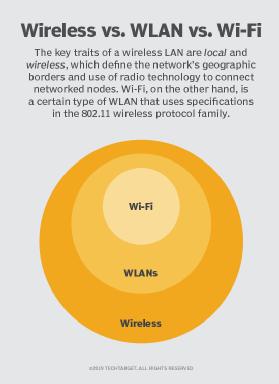

Although the terms WLAN and Wi-Fi are used interchangeably, the two wireless technologies differ. Wireless LAN uses radio technology to connect nodes, while Wi-Fi is a type of WLAN.

The notion of wireless continues to be complicated in business environments. Depending on the specific wireless context or application being discussed, your assumption of what wireless LAN means might differ from mine -- even if we're engaged in the same conversation.

Forget about wireless personal area networks, like Bluetooth, and wireless WANs with their respective network devices. Even without these wireless network topologies, there's enough to keep straight with the topic of WLAN. In particular, let's explore the differences between WLAN vs. Wi-Fi.

What is a WLAN and how does it work?

A WLAN is a local area network that uses radio technology instead of wiring to interconnect networked nodes.

To tackle the generic WLAN construct, we first need to review what local area network means. A LAN is generally a network contained within a building or campus, representing a geographical or functional construct usually connected via cabling of various sorts. Add a W to LAN, and it becomes a wireless LAN. Wireless technology either extends the LAN, replaces parts of it or both.

The terms WLAN and Wi-Fi are often linked and used interchangeably, but problems arise with that habit. A WLAN can be built on various wireless technologies, including Wi-Fi, cellular and Bluetooth, for example.

To illustrate the difference between WLAN and Wi-Fi, I'll share a story. I once consulted on requests for proposals and implementation projects involving lighting control and building alarm systems. Each used WLAN for its wireless connections. Upon hearing the projects involved WLAN, I thought: "Oh, boy, we might not want critical services on Wi-Fi."

But, after digging into the product literature, I learned these WLANs used different radio technologies and had nothing to do with Wi-Fi. In each case, some form of router sat between the LAN and the proprietary wireless transceivers in play.

So, again, a WLAN uses radio technology to connect nodes within a LAN, but it might not necessarily use Wi-Fi.

How do you create a WLAN?

Those who create networks of any sort for a living know network design needs to enable operational goals. When a WLAN presents the right paradigm to achieve specific goals, a qualified network engineer or architect considers which components and technology work best for a given situation. Wireless technology might be part of a wire-intensive topology, or it might be the dominant technology in play.

Creating a WLAN is an exercise in requirements, product and technology selection, and implementation, which can yield a range of final system topologies.

Here are the primary steps to create a WLAN:

- Gather requirements. What problem is being solved? What applications are being enabled?

- Identify which client devices will be used and their operational needs. Building sensors have different power, security and bandwidth requirements than tablet PCs, for example.

- Identify the right WLAN products, and evaluate which underlying LAN connections and wiring the network needs.

- Design the WLAN layout. Ideally, a wireless professional does this.

- Install the WLAN components.

- Verify wireless coverage and performance.

- Verify the design meets operational requirements.

- Identify a system owner responsible for updates, troubleshooting and lifecycle replacements.

What are the benefits of WLAN?

The use of any wireless technology can empower enterprises in many discrete areas. WLAN, specifically, includes the following advantages:

- The reduction of physical wires and associated pathways saves network costs.

- Network engineers can build networks virtually anywhere using the right WLAN technology.

- Client device portability and mobility enable new workflows.

- Network teams can address short-term, temporary networking needs more easily.

- Moves, adds and changes to the system are generally easier than with wired connections.

What are the challenges of WLAN?

Trading one technology for another presents both advantages and disadvantages. Despite WLAN's benefits, network teams have to consider the following realities:

- Proper WLAN design and implementation require specific skills.

- Wireless technologies of every sort are subject to interference on the radio waves in use.

- Many proprietary, nonstandards-based technologies are available that can be challenging to support.

- WLAN network and client devices can have varying feature sets.

What is Wi-Fi and how does it work?

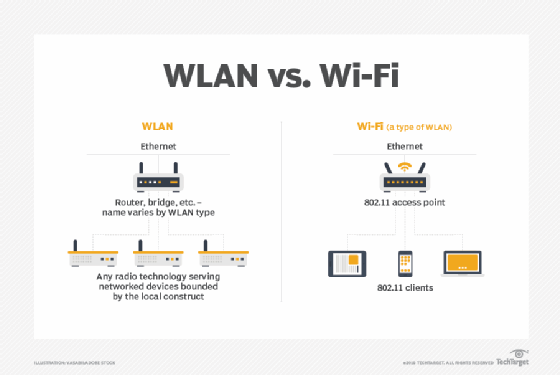

Wi-Fi is the wireless LAN technology that uses the IEEE 802.11 standards and nothing else. Through the years, different evolutions of Wi-Fi have emerged, culminating in the new 802.11ax standard.

Each version of the 802.11 standard is written for compatibility with 802.3 Ethernet -- the most common LAN type -- because Wi-Fi typically extends the edge of a wired network. Peer-to-peer Wi-Fi is also written into the 802.11 standards, and it frequently works in parallel with full-blown WLAN deployments -- wireless printers are one common example.

Wireless access points (WAPs or simply APs) act as Layer 2 bridges between 802.11 and 802.3 standards in enterprise networks. Wireless routers in a home network have an AP built in under the hood. A client device wirelessly connects to the network through an AP.

Is Wi-Fi a wireless LAN?

Wi-Fi networks are absolutely WLANs. But the important nuance is Wi-Fi is not the only type of WLAN.

Consider my aforementioned lighting control project. In this case, the company uses frequencies around 430 MHz to connect switches, light fixtures and controllers to form a WLAN in a given space. While a Wi-Fi AP bridges 802.11 to 802.3, in this case, the system uses its own hub to connect back to the LAN. The alarm system has its own WLAN as well, using its own spectrum.

Wi-Fi is pretty much the only WLAN that services human clients directly, although in-building cellular may qualify as well. Most other WLANs likely service headless client device nodes.

Another consideration is multiple, colocated WLANs and how they might interact. If I turn on my commercial-grade Wi-Fi tools, I won't see the lighting or alarm WLANs because they're both in different frequency ranges. Remember, Wi-Fi is in 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz and now 6 GHz since the advent of Wi-Fi 6E.

But, if I try to run two concurrent WLANs of any one type, I'm asking for trouble. Just like two Wi-Fi networks in the same space can ruin each other's performance, the same is true with two lighting WLANs, two alarm WLANs or two of any other type of WLAN that might use the same frequencies. Any WLAN needs proper design, and it needs to respect other WLANs in the same space.

Which is better: WLAN or Wi-Fi?

On the surface, it might seem silly to ask whether WLAN or Wi-Fi is better, given that Wi-Fi is itself one flavor of WLAN.

But, as ubiquitous as Wi-Fi has become, network teams might find Wi-Fi isn't always the best choice when they need a WLAN. For general-purpose user access, Wi-Fi continues to be the de facto standard. But, where an increasing number of IoT and headless devices are concerned, teams are likely to choose from better WLAN choices.