lassedesignen - Fotolia

Understanding the evolution of Ethernet

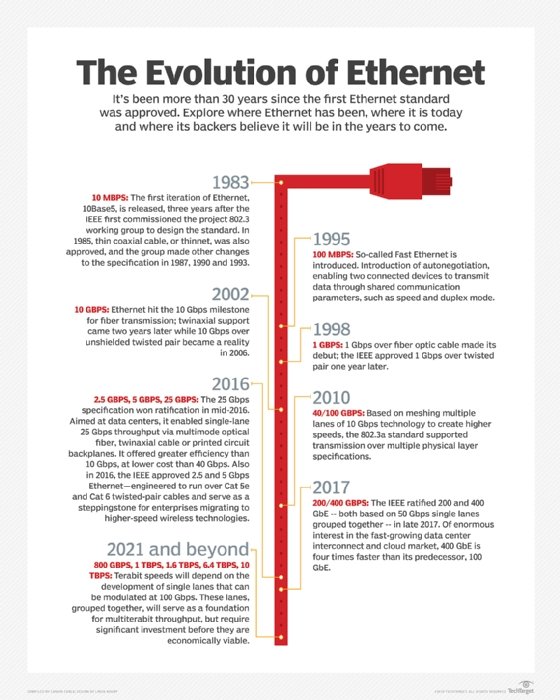

First developed by Xerox PARC in the 1970s and ratified by IEEE as a standard in 1983, the evolution of Ethernet has taken this LAN technology through dozens of specifications.

For hundreds of years, scientists believed a mysterious substance known as ether served as the medium for light to disperse through space. The notion was ultimately dismissed once physicists discovered that photons act as both particles and waves. But the archaic word lives on in the modern term Ethernet -- the technology by which bits of information travel through complex computer networks.

Created at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) in the early 1970s by a team that included Robert Metcalfe and David Boggs and ratified by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) as a standard in 1983, Ethernet has become the dominant LAN technology. Decades after its initial specification, the evolution of Ethernet continues.

Let's take a look at the technology's progress over the past several decades and explore where experts think it could head in the years to come.

Robert Metcalfe invents Ethernet

The evolution of Ethernet officially began in 1973 when engineer Robert Metcalfe introduced the concept in a memo he wrote while working at Xerox PARC. The technology, as Metcalfe described it, linked discrete advanced computing workstations and enabled them to communicate with each other, as well as with devices like high-speed laser printers. Together, these interconnected endpoints became more than the sum of their parts: an environment we now recognize as the world's first high-speed LAN.

Metcalfe based Ethernet on what he learned from the Aloha system -- an earlier networking project that began at the University of Hawaii in 1968. Aloha aimed to connect remote workstations across the Hawaiian Islands to a central computer at the main Oahu campus.

Using the rudimentary Aloha protocol, a station would transmit a frame over a common data channel and then wait for confirmation it had reached its destination successfully. If the station didn't receive confirmation within a given period, it assumed a collision had occurred with another frame that a different node happened to send simultaneously. That station would continue to blindly resend the data until it achieved successful transmission. But, as nodes and transmissions increased, more collisions would occur, and the network became less efficient. An Aloha variation called slotted Aloha sought to minimize network contention problems by precisely coordinating individual transmissions, assigning them designated time slots via beacon signaling.

Metcalfe's Ethernet experiment -- which he initially referred to as the Alto Aloha Network -- included several revolutionary new features that enabled significantly more efficient use of a network channel. Together, this set of rules -- now codified as the Carrier Sense Multiple Access/Collision Detect protocol -- enabled stations to monitor the availability of a shared path and detect collisions when two devices happened to send data at the same time. When frames did collide, the system would discard them, and each station would wait a randomly assigned length of time before reinitiating its transmission -- pausing and repeating as many times as necessary, in a process known as exponential back-off.

By 1973, Metcalfe felt the technology had outgrown its original name, Alto Aloha Network, and rechristened it Ethernet. Four years later, Metcalfe and Boggs -- along with Charles Thacker and Butler Lampson, also of Xerox -- would successfully patent Ethernet technology.

IEEE standardization

Xerox worked with two other vendors -- Digital Equipment Corporation and Intel -- to publish the first 10 Mbps Ethernet specification in 1980. Meanwhile, the Local and Metropolitan Area Networks (LAN/MAN) Standards Committee at the IEEE set out to develop a similar open standard.

The LAN/MAN committee -- which applies the number 802 to all its standards -- formed an Ethernet subcommittee, dubbing it 802.3. In 1983, the IEEE approved the original 802.3 standard for thick Ethernet (10Base-5), with official publication in 1985. Next, it ratified 802.3a (10Base-2), a version of 10 Mbps Ethernet that uses thin coaxial cable, followed by twisted pair (10Base-T) and fiber optic (10Base-FL) standards.

In 1995, 100 Mbps Ethernet -- also known as Fast Ethernet or 100BASE-T -- debuted, introducing autonegotiation. This new feature enabled two network devices to communicate and establish the best shared mode of operation -- i.e., speed and duplex mode.

Three years later, 802.3 hit a new milestone with the introduction of Gigabit Ethernet (1000Base-T) -- first over fiber optic cable and, subsequently, over twisted pair cabling.

The evolution of Ethernet continued with 10 Gbps in 2002 -- first over fiber, then twinaxial and, finally, unshielded twisted pair cables. Eight years later, the IEEE approved 40 GbE and 100 GbE, speeds achieved by aggregating 10 Mbps lanes.

In 2016, driven by demand from hyperscale web companies, the IEEE ratified 25 GbE, which promised to be 2.5 times faster than 10 GbE but more cost-effective than 40 GbE. Because it improves throughput by increasing the capacity of a single lane -- rather than aggregating multiple lower-capacity lanes -- 25 GbE requires less cable and power and has higher port density than 40 GbE. In some cases, an upgrade to 25 GbE lets data center operators extend the life of top-of-rack switches and avoid a full rip-and-replace upgrade of cabling infrastructure.

The following year, in late 2017, the networking industry saw the ratification of 200 GbE and 400 GbE, both based on 50 Gbps single lanes. As the appetite for faster bandwidth skyrockets -- especially among cloud providers and other hyperscale data center operators -- the standards committee now turns its attention to 800 Gbps, 1 Tbps and beyond. The evolution of Ethernet continues.