What are containers and how do they work?

Containerization is a new approach to application provisioning for many enterprises and requires a fundamental understanding of how containers operate, where they differ and the pros and cons.

Containers offer an attractive alternative to physical servers and VMs, which has prompted many IT organizations to consider them for application provisioning. But what are containers, and how do they interact with the application and underlying infrastructure?

A basic physical application installation needs server, storage, network equipment and other physical hardware on which an OS is installed. A software stack -- an application server, a database and more -- enables the application to run. An organization must either provision resources for its maximum workload and potential outages and suffer significant waste outside those times or, if provisioned resources are set for average workload, expect traffic peaks to lead to performance issues.

VMs get around some of these problems. A VM creates a logical system that sits atop the physical platform (see Figure 1). A Type 1 hypervisor, such as VMware ESXi or Microsoft Hyper-V, provides each VM with virtual hardware. The VM runs a guest OS, and the application software stack interprets everything below it the same as a physical stack. Virtualization utilizes resources better than physical setups, but the separate OS for each VM creates significant redundancy in base functionality.

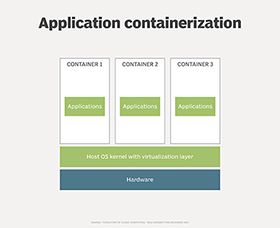

Containers provide greater flexibility than virtual and physical hardware stacks. A basic application container environment, as seen in Figure 2, runs on physical -- or virtual and physical -- hardware, a host OS and a container virtualization layer directly on the OS. Containers share the OS and its functions instead of running individual OS instances. This greatly reduces the resources required per application. Docker, Rkt (a CoreOS container runtime acquired by Red Hat), Linux Containers and Windows Server Containers operate generally in a similar manner.

The benefits have downsides

OS sharing led to problems in early containers. Code that required raised privilege at the OS level opened businesses to the potential of malicious entities able to gain access to, and attack, the underlying platform to bring down all the containers in the environment. Some organizations ran containers within VMs to combat the issue, but others argued that doing so destroyed the point of containers. Modern container environments mitigate these security issues, but many organizations still host containers in VMs for security or management reasons.

The fact that all container applications must use the same underlying OS is a strength, as well as a weakness, of containerized applications. Every application container sharing a Linux OS, for example, must not only be based on Linux, but also on the same version and often patch level of that Linux distribution. That isn't always manageable in reality, as some applications have specific OS requirements.

Containerize the system

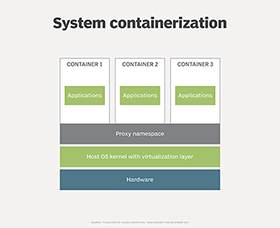

System containerization, demonstrated in Figure 3, resolves this tangle. System containers use the shared capabilities of the underlying OS. Where the application needs a certain patch level or functional library that the underlying platform lacks, a proxy namespace captures the call from the application and redirects it to the necessary code or library held within the container itself.

System containerization is available from Virtuozzo. Microsoft also offers a similar approach to isolation via its Hyper-V containers.

What are containers enabling?

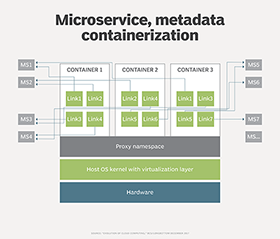

Applications have evolved through physical hardware to VMs to containerized environments. In turn, containerization is ushering in microservices architecture.

Microservices create single-function entities that offer services to a calling environment. For example, functions such as calendars, email and financial clearing systems can live in individual containers available in the cloud for any system that needs them, in contrast to a collection of disparate systems that each contain internal versions of these capabilities.

Performance benefits from hosting such functions in the cloud. Sharing the underlying physical resources elastically with other functions minimizes the likelihood of hitting resource limits.

Microservices also offer flexible, process-based methods to handle business needs in an application architecture. Rather than code that tries to guess at the business process and ends up constraining it, microservices create a composite application of dynamic functions pulled together in real time that enables a business to respond to market forces more rapidly than monolithic applications can.

As shown in Figure 4, the container doesn't carry around physical code within it, but rather a list of required functions that it pulls together as required. The container manages areas such as technical contracts and process audits.

IT professionals can soon expect to see how containers will evolve from here. Containers exist in a highly dynamic and changing world. They optimize resource utilization and provide much needed flexibility better than their predecessors, so enterprise IT organizations should prepare to use them.