The post-pandemic workplace empowers some, not all

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated investments in automation and has sent turnover soaring, a new reality that benefits some employees but is a disadvantage to others.

Sterling National Bank believes chatbot automation is smart enough to reduce the need for customer service representatives. Its implementation is now paying off, especially as the U.S. shifts to a post-pandemic workplace.

Filling customer service rep openings became challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child care responsibilities, stimulus payments and other factors may have held potential applicants back from applying for jobs that required them to work in its on-premises customer service center, said Luis Massiani, chief operating officer and president of the bank, which is based in Pearl River, N.Y.

The pandemic prompted the bank to accelerate its chatbot deployment, which began in 2019. Since the project began, Sterling has reduced its 60 to 65 full-time equivalent (FTE) call center employees, based on seasonal flows, to about 35 to 40 FTEs. It also has calculated an efficiency gain of more than 30%.

For Massiani, the results from investing in job automation may be empowering. Increasing use of automation enables the bank to add new customer offerings "at substantially lower operating costs," he said.

"We are going to continue to reduce the amount of calls that are handled by human beings," he said.

Increasing investment in job automation is a trend emerging from the pandemic, although just how much COVID-19 has influenced that trend is hard to quantify. What is clear is with job vacancies at a high, knowledge workers are using newfound power to seek changes to the workplace that benefit them, while others are facing a different struggle altogether -- a battle for survival.

Hourly workers face challenges

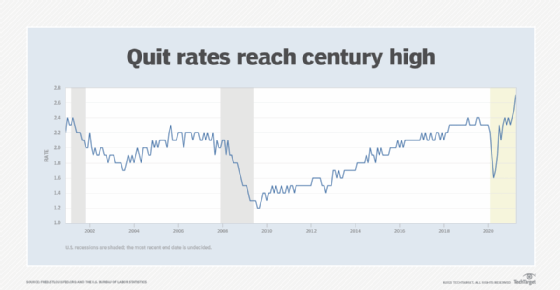

With more than nine million job openings in April, workers are quitting at high rates in search of better opportunities. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded the quit rate at 2.7% -- the highest so far this century.

The industry experiencing the highest percentage of quits per month, at 5.6%, is in the government's "accommodation and food services" category, which covers hotels and restaurants, including fast food, reported the BLS. Some firms may be raising wages as an incentive.

In May, for instance, McDonald's announced a plan to raise wages at corporate-owned restaurants by an average of 10%, with a range of $11 to $17 an hour for a job in the starting crew.

But wage increases like this may be outliers, according to one researcher. Indeed, workers, especially hourly workers, may face the same battles over wage and schedules that they did before the pandemic.

"We've seen a handful of companies announce wage increases, but they remain the distinct minority of firms," said Daniel Schneider, a professor of public policy at Harvard.

Schneider studies issues affecting hourly workers through the Shift Project, which gathers data from workers at large service sector firms in retail, food services, hospitality and other industries to assess working conditions. The "vast majority of service-sector workers experience instability in their weekly work schedules," according to this group. The pandemic, so far, hasn't changed scheduling practices, Schneider said.

"We are still working on this, but it doesn't seem like there's been any real movement toward greater work schedule stability and predictability," Schneider said.

Erratic schedules increase turnover, which is costly not only to firms but to workers, he said. "Rather than moving on to better jobs, we find that workers who leave experience downward wage mobility," he said.

Hourly workers are less likely to be provided benefits and more likely to experience "on-call scheduling," where workers are called in only if needed, keeping hours and pay unpredictable, said Carlos Moreno, the state director of the Working Families Party in Connecticut, which is part of a group that was working to make Connecticut the second state, after Oregon, to adopt a fair workweek law.

On-call shifts put employees in "difficult positions where they have to scramble to find last minute childcare to accommodate an employer's needs," Moreno said.

Fair workweek laws face opposition

The Connecticut bill mandated that employers offer new hours to existing employees before hiring externally, which gives part-time workers access to more hours and potentially enough to qualify for benefits. It required advance notice of schedule changes and pay for canceled shifts.

"All those kinds of things that would have really added a little bit more stability" to employees, Moreno said.

The legislation faced opposition from business groups, including the Connecticut Restaurant Association. In its hearing testimony, it described on-call scheduling as "an essential aspect of the hospitality industry" and useful for such problems as canceled dinner reservations or closure of outdoor dining areas due to weather.

This bill, which impacted employers of 500 workers or more, passed Connecticut's Senate in May but stalled in the House. Moreno plans to try again next year.

In Congress, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) along with U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) has been trying to get a national predictive scheduling law passed since 2015. Similar to some state laws, it would require a two-week advance notice of work schedules. In April, she renewed her call for the "Schedules that Work Act" at a Senate hearing.

"Employers can change someone's schedule without any prior notice, and this type of disruptive scheduling practice hits low-income workers the hardest," Warren said.

While stalled on the federal level, predictive scheduling laws are gaining ground in some cities. New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Philadelphia and Chicago are among the cities that have adopted some version of it.

Predictive scheduling software

As a result of these laws, scheduling software vendors advertise that their systems will ensure compliance with fair workweek laws and help employers avoid fines, which can be costly. In April, New York City filed a lawsuit against Chipotle Mexican Grill, reportedly seeking about $150 million in fines for fair workweek violations.

For businesses, mapping variable business demands to employee needs is a hard problem, in part, because labor needs, such as cashiers, can vary frequently during a day, said Richard Tarpey, an assistant professor of management at Middle Tennessee State University with expertise in scheduling systems.

"It's going to be very difficult to marry those two concepts together, a very predictable work week and meet the variable demands of a business," Tarpey said.

More certain is the automation of certain job functions, Tarpey said, pointing to examples such as Amazon Go, a chain of cashierless convenience stores. "I think most companies are going to attempt to automate everything they can automate," he said.

At Sterling National Bank, automation came in the form of Amelia, an IPsoft company and conversational AI developer, for voice and text deployment. The bank, which employed 1,619 as of March, named its chatbot implementation Skye.

Sterling's Massiani said the chatbot deployment is in an ongoing "test and learn" phase. The effort started with relatively simple use cases, such as enabling customers to check balances and reset passwords. As the bank gains more experience with the technology, it is increasing the sophistication of customer questions Skye can address, such as mortgage help.

"We're always going to be in the testing phase," Massiani said, in the sense that "we're going to figure out ways to essentially use the technology for more." But there's no doubt about the effectiveness of the technology for Sterling. "This thing absolutely works," he said.

Some customers, especially longtime consumer banking customers, still want to talk with a human. But each year, the bank's clientele has "a much greater composition of folks who are more comfortable using technology," Massiani said.

Automation in post-pandemic workplace

Increasing investment in automation was a trend noted early in the pandemic by Federal Reserve Bank officials, and new data supports it. In a survey this month, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found that 41% of manufacturing firms it surveyed are now investing or planning to invest "in labor-saving automation strategies at a faster pace than in the past." Labor shortages were driving this investment, according to the survey.

It's not clear how much impact job automation will have on overall employment or how rapidly automation will be adopted. But the Bureau of Labor Statistics is forecasting a decline in customer service representatives by 2% between 2019 and 2029 "as more tasks become automated." This forecast was made before the pandemic prompted more spending on automation.

Brian Kropp, a vice president of research at Gartner, believes the government's estimate of a 2% decline in call workers is conservative because of the technology improvements. But the remaining customer service representatives will earn more, because they will be tasked with handling the most difficult calls that require experience, he said.

The hiring difficulty firms are facing is acting as an accelerant for technology investments, Kropp said. For many, the investments aren't simply focused on job elimination but job augmentation, where the technology enables employees to be more productive.

"It's a talent scarcity problem that's occurring, which is why a lot of these other investments are starting to increase," Kropp said.

HR's self-inflicted turnover problem

The most empowered group of employees in the post-pandemic workplace are knowledge workers in search of better pay and flexibility. But some of the problems that HR is having in reducing turnover may be self-inflicted.

The higher quit rate is "really a workforce in search of higher degrees of flexibility" and wellbeing "and then being rewarded for their work at the same time," said Michael Stephan, U.S. human capital national managing partner at Deloitte.

Some employers aren't offering enough flexibility with their hybrid work models or are leaving employees hanging about their remote and hybrid work policies, Stephan said. The indecision has prompted some employees to find employers with a clearer plan about the post-pandemic workplace, he said.

Pay is also a big part of turnover, Stephan said. "We are absolutely seeing in the market a significant hike in offers, across all industries," he said.

Employers may not be doing enough to listen to employees, according to an 11-country study of 4,000 workers by the Workforce Institute at UKG and Workplace Intelligence. Released in June, the study found that 63% of employees "feel their voice has been ignored in some way by their manager or employer," a situation that can foster turnover.

"Attrition is the worst possible outcome," said Dan Schawbel, managing partner of Workplace Intelligence, an HR consultancy. "You can't grow as a company if you're too busy trying to replace your employees."

Employees today "have more power in this current economy, so you almost have to bend to them," Schawbel said.

The sense of new power in the workplace extends to recent college graduates, said Steven Rothberg, the founder and chief visionary officer of College Recruiter, a job site that focuses on internships and entry-level positions for recent graduates.

"A college student looking for an internship two years ago might have been willing to take an unpaid internship in order to get the experience," Rothberg said. "Today, the thought of taking an unpaid internship would just be incomprehensible."

Patrick Thibodeau covers HCM and ERP technologies. He's worked for more than two decades as an enterprise IT reporter.