Getty Images

Managing a multigenerational workforce: Tips from an expert

A recruiting expert with 26 years of experience provides advice on how organizations can keep a multigenerational workforce engaged without compromising the company mission.

Change is inevitable and a constant that HR leaders know well. Ken Schmitt is a recruiting expert with 26 years of experience as well as CEO and founder of recruiting firm TurningPoint, which he started in 2007.

Schmitt presented a session in BrightTALK's recent virtual Editorial Summit, HR Strategies: Future-Proofing Your Workplace, where he discussed how companies can better prepare their workforce to thrive and stay engaged. Following Schmitt's live presentation, we met to delve deeper into some of the topics that he explored in his talk.

Having launched his business during the 2007 financial crisis, Schmitt draws on his lessons learned to handle everything from the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath to different generations in the workplace and beyond. His biggest takeaway: "Don't be afraid to take risks" -- and there's more where that came from. Dive into our discussion covering key workplace trends, including generational assumptions, worker expectations and employee tenure. Plus, access his full presentation on our BrightTALK platform.

Editor's note: The following was edited for length and clarity.

Ten years ago, the median job tenure was 4.6 years, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. How has this changed in 2024? Additionally, is there any relationship between job tenure and career advancement?

Ken Schmitt: That's a good question. I think it's a difference between expectations and the mentality of today's workforce, right? I grew up in the 70's and 80's, and back then, people were still going to work right out of school or even [not going] to college. You work right out of high school, and you work your way up, and you're expected to be at the same company for 30 years. You had a pension. You got the proverbial gold watch at the 30-year mark, and then you retired.

That was the mentality back then. Fast forward to today, and it's more of what we call a "portfolio career," where everybody is expected to have multiple jobs -- not just jobs from different companies but even several careers over their lifetime. The expectation of the candidate on the employee side is, "Hey, I'm going to be here for XYZ years. I'm going to learn everything I possibly can to prepare me for the next step. In some cases, that next step will be a leadership role in my current company. But in most cases, I'll end up going somewhere else. How can I maximize my time here?"

From the employer side, they also realize, "Alright, we're not going to have these people for 30 years. We're going to have them for three to five years. How can we, as the employer, maximize what we get out of them?" [That means] their productivity, their output. But also, how can we prepare them longer term to keep them here? Maybe [we can keep them] a little bit longer if they know that we have their long-term career and best interests at heart as well. I think it's just a shift.

Is the median job tenure today less than 4.6 years?

Schmitt: It's 3.5 years now, so that's a big difference. It's a 25% change from 4.6 to 3.5. That's a pretty big difference, and the question is, is it a bad thing? Is it a good thing? I don't know. I just think it's a change for leaders that have been around for a long time, who grew up in the business world in the 80's and 90's where they expected loyalty. They have to realize now when they're looking at candidate resumes that if somebody's been in a job for only two or three years, that doesn't make them a job hopper. It used to, but not anymore. Now it's someone who's typical, right? If someone's in a job for 20 years, you know that can be a little bit more of a negative than a positive because those folks only know one company, one way of doing things, one dynamic, one set of resources. Can they adapt and change if they change companies?

I don't think it's a good or bad, right or wrong thing. I think it's just a difference that we all have to adjust to.

In a post-COVID-19 world, how can organizations keep employees from leaving?

Schmitt: It's going to sound simple, but it comes down to two things: transparency and communication. Employees, especially Gen Z [employees], expect to know what's happening in their business, how their job impacts the overall business and how the company itself impacts the social fabric of what's going on in the world outside of the company as well. That transparency is important.

I would never have gone above my immediate boss to air any grievances or concerns. It's not the same way for Gen Z. They say, "Hey, I have an issue. I have a challenge, and it's not being addressed; it's not being resolved. I'm going to talk to the person that I know can make a difference whether or not that person is my immediate boss or somebody above that." Transparency is important, but beyond that, it's a matter of general communication.

What is employer branding and where do companies start with it?

Schmitt: It's a simple thing, but I think every company is focused on their brand in terms of their product or service. What do we offer? Who's our customer base? But few companies take the time to think about what their brand is. As an employer, in other words, what is it like to work with that company? Everything [is considered], from the number of hours that you work to whether you work from home or in the office. Are you a pre-IPO company or a company that's looking to be sold to a private equity firm and you're working 60-70 hours a week? Is it more of a company where we value mental health, so our benefits package is good, and we provide extra PTO? None of those are a judgment call. It's just, what is your brand as a place to work?

Where you start is to ask your employees: How would you define us? How would you describe our employer brand? You can get a good sense for whether or not people feel aligned based on whether or not current employees are referring future employees. That's always the best way.

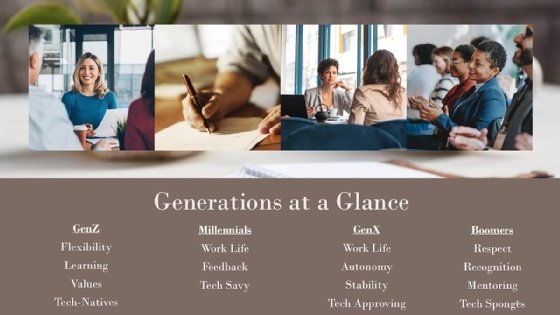

Everyone talks about Gen Z, millennials, and boomers being so different at work. But what's true and what's just a myth?

Schmitt: That's a great question. Everything is going to have different varying degrees of truth or myth, I guess. But one that pops up most often is that people think that boomers can't possibly learn new technology. So don't hire somebody who's more seasoned -- as we say in recruiting -- into a tech-intensive organization because they're going to flounder. That's untrue. I know a lot of older folks that do well with technology, so I think that's a myth for sure.

On the other side of the spectrum, Gen Z, people say there's no work ethic. They don't care about the job; they're going to jump ship. All they care about is social issues. Mental health is such a big deal, and everything is a crisis. They can't even handle a phone conversation.

Again, that's not true or false across the board. It's true for some people, but the majority of Gen Z employees that I know are very, very strong workers. They're dedicated. They have a good work ethic. They want to do well, and they want their employer to do well. They want to make money also, but most Gen Z employees out there are not in a job because they want to get into a corporate leadership role. Some are, but some aren't.

How can organizations foster inclusiveness and diversity of thought in a way that is authentic and meaningful?

Schmitt: The biggest thing is making sure that it's clear to the organization that this is not just a shiny object -- that this is something that is what we call "the tone at the top," meaning that the CEO believes in this long term and it's not going to be just a fad. Because if they don't believe in it, then everybody below the CEO is going to say, "Oh, yeah, this is what we're doing right now. It'll go out the window and be totally unimportant in six months. So why even bother?"

That's the first thing: making sure that it's a tone that's set from the top throughout the organization. Then, the way that you hire people is important: not looking at the same people from the same schools or from the same industry, for example, or the same age group. Looking at people that don't even have a college degree at all. Folks without a college degree have an amazing work ethic. It's all different scenarios out there that create fantastic work ethics that are beyond the traditional background of having a college degree.

Fostering diversity means making sure that it's not just a window dressing saying, "Oh, yeah, we invite all opinions and all ideas," and then dismissing everybody that's not like you. Instead, say, "Alright, we want to acknowledge and reward and applaud ideas coming from everybody. It doesn't matter what your background is. It doesn't matter what your title happens to be or what department you're in." Applaude and encourage those ideas and truly look at those ideas as things that you can implement in the organization. That's where I think the inclusiveness comes into play.

Natasha Carter is the director of partnerships and event content at TechTarget. Prior, she served as the director of audience development at TechTarget. Carter also co-leads diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives across the organization.