Hawthorne effect

What is the Hawthorne effect?

The Hawthorne effect is the modification of behavior by study participants in response to their knowledge that they are being observed or singled out for special treatment. In the simplest terms, the Hawthorne effect is increasing output in response to being watched.

The term Hawthorne effect arose in connection with the Hawthorne studies, which were a groundbreaking series of studies beginning in the 1920s that tested the impact of working-condition variables on employee productivity. Most experts do not believe there was a so-called Hawthorne effect in the Hawthorne studies, but it persists as a widely used term.

Complicating the use of the term the Hawthorne effect is its inconsistent meaning from use to use; it is often used for a number of effects beyond the aforementioned. As for the use of the term the Hawthorne effect in psychological and health studies, many in the scientific community say it should be replaced with more specific terminology pertinent to whatever is being studied.

The Hawthorne studies

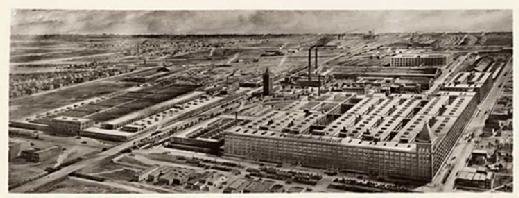

The Hawthorne studies consisted of a series of worker productivity studies, which began around 1924 at the Western Electric plant in Illinois, near Chicago.

Western Electric was the manufacturing unit of the conglomerate the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), which, from its founding in 1876 to its breakup in 1984, had a near monopoly on the telephone industry. Western Electric manufactured telephones, cables, and switching and transmission equipment. And by 1929, upward of 35,000 men and women worked at its main factory, Hawthorne Works.

Given the highly specialized and complex manufacturing of certain equipment, Western Electric was keen to optimize production and applied the principle of scientific management, which held that there was "one best way" to perform any given task, and authority should be held solely by management.

The Hawthorne studies tested such variables as the effect of lighting, work breaks and pay incentives. They also included an extensive interviewing program, where employees could talk about their grievances and concerns.

The Hawthorne studies included several productivity studies and worker groups. When the Hawthorne studies ended in 1932, more than 20,000 employees had participated in some way. Many accounts about the Hawthorne studies focus only on a single group of workers and ignore the absence of support for the so-called Hawthorne effect and the other variables that contributed to productivity gains.

Myth of the Hawthorne effect

The illumination studies sought to prove that artificial lighting improved productivity. The studies were part of a more widespread series of lighting studies in the industrial sector. This widespread series -- as many studies of the time -- depended on collaborations such as those between companies and universities. The illumination studies arose primarily at the campaigning of the electrical industry, which was working to have factories rely more heavily on artificial lighting.

One widely reported definition of the Hawthorne effect rests on the story that no matter what variables were changed -- typically in the illumination studies -- worker productivity increased. In other words, the variables did not matter; the instrumental factor was that study subjects were being observed. This straightforward account of productivity is false, according to a number of sources, including a 2011 study in the journal Human Factors.

More modern analysis by researchers of the Hawthorne lighting studies, including some based on the discovery of original documentation, showed inconsistencies between light levels and productivity, and determined that experiment methodology was seriously flawed, according to Human Factors.

Most publicized accounts of the Hawthorne studies centered on one group of women, five telephone relay assemblers, who had been moved from the big open floor of the relay assembly department to a test room for the purposes of the study.

The supervisors in the test room were friendly and tolerant, unlike the authoritarian foreman in the usual working conditions. The test room was separate, smaller and quieter, with other aspects of more humane working conditions, and the women developed deep friendships.

Many other co-founding factors existed, including the financial incentives of better payment and more individual accountability and the effect of continuous performance feedback. The test-room women were paid an at-the-time seemingly astronomical amount, and earnings was among the top three cited reasons why these women preferred the test room over the usual working conditions, with financial incentives functioning as a clear source of motivation.

In another study, "the mica-splitting test," where another small group of women was moved into a test room, women pointed to the quiet, to the ability to get things they needed quickly and to breaks as powerful reasons for liking the test room, according to the book Management and the Worker.

Western Electric Company Hawthorne Studies Collection © 2007 President and Fellows of Harvard College; all rights reserved. https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/hawthorne/big/wehe_073.html

Source: https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/hawthorne/big/wehe_073.html; Baker Library

In direct opposition to the so-called Hawthorne effect, a small group of male workers was studied in what is typically called the "bank wiring study." Productivity did not improve. Instead, informal but powerful worker norms set what was deemed a fair productivity standard to protect slower workers, and this level was enforced by social pressure.

Hawthorne studies' contribution to modern management

The 1920s were marked by industrialism. Workers -- many of whom were immigrants or first-generation Americans -- faced long, monotonous workdays and were considered to be interchangeable parts of a big industrial "machine." It was an era during which many educated and higher-class Americans considered these factory workers to be intellectually and biologically inferior, ideas found in dystopian works by authors such as Aldous Huxley and George Orwell.

In contrast, the Hawthorne studies pioneered a sea change in the perception of what constituted appropriate treatment of workers and what constituted a more ideal management style. The result was a more humanistic view of workers, what is called often termed the human relations school of management.

Indeed, lead researcher Elton Mayo -- in contrast to the authoritarian view of ideal management -- concluded that job satisfaction increased when workers had the freedom to decide on output standards and their ideal worker conditions and were able to collaborate.

Mayo believed good management was not a matter of solving problems simply with technical efficiency, but instead required skills in human relations. These included what would now be called emotional intelligence and soft skills, such as counseling, motivating and communicating -- a far cry from scientific management's symbol of a man with a clipboard timing workers.

Despite criticisms of the Hawthorne studies, the thinking that emerged shaped its researchers' views and influenced thinking about management at Harvard Business School and other major influencers.