Getty Images/iStockphoto

Integrating Social Determinants of Health into the EHR

Addressing social determinant requires integration of this information into the EHR. Otherwise, providers will not be able to use it for clinical decision-making.

It’s now considered common knowledge that providers need to address a patient’s social determinants of health. These factors such as an individual’s financial situation, ability to get healthy food options, and access to reliable transportation can be more important to an individual’s health outcomes than the actual clinical care he receives.

In fact, commonly cited statistics show that clinical care influences just 10 to 20 percent of a patient’s outcomes, while social determinants of health impact the remainder. If a patient cannot adhere to his hypertension care plan if the medication is too expensive for him to buy every month, then outcomes will suffer. Similarly, outcomes will not improve for an obese patient, if she cannot afford healthy food options or get to a grocery store miles away from home.

But providers are often unaware of this information and some have previously felt it was not their responsibility to address. Only as the evidence has grown have providers felt a push to incorporate these non-traditional risk factors into their clinical decision-making.

“Slowly but surely, the evidence base is showing the benefits of doing social needs screening and social needs interventions. Until recently, there wasn’t an empirically strong evidence base, even though intuitively it’s quite obvious that if you can address the patient’s food insecurity, it’s going to help their diabetes outcomes,” said Rachel Gold, PhD, MPH, senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research and lead research scientist at OCHIN, Inc.

Providers can screen for this information in multiple ways: paper questionnaires before a patient sees the clinician, conversations when discussing treatment options, or publicly available data sets that give context to where a patient lives and works. The last option uses data from sources such as the Census or American Community Survey on neighborhood-level demographic information and links this to the patient’s home address under the assumption that it is reflective of the patient’s experiences.

“Slowly but surely, the evidence base is showing the benefits of doing social needs screening and social needs interventions."

Regardless of the method of collection, this information needs to be incorporated into a patient’s medical record in order for providers to use it for clinical decision-making. Similar to how a doctor can view a patient’s previous medical diagnosis and use that information to inform future care, doctor’s need access to a patient’s social determinants of health if they are to consider it when providing treatment options.

However, interoperability, the physical location of this information in the EHR, and a lack of standard codes for this data challenge a provider’s ability to truly understand a patient’s social determinants of health.

“What we need is some way where we take patient-level screening about social risk factors and apply that information to decisions about medications, referrals, lifestyle recommendations, and other treatment plan components,” emphasized Laura Gottlieb, MD, MPH, associate professor of family and community medicine at University of California, San Francisco.

Incorporating social determinants of health information into the EHR is one of those ways.

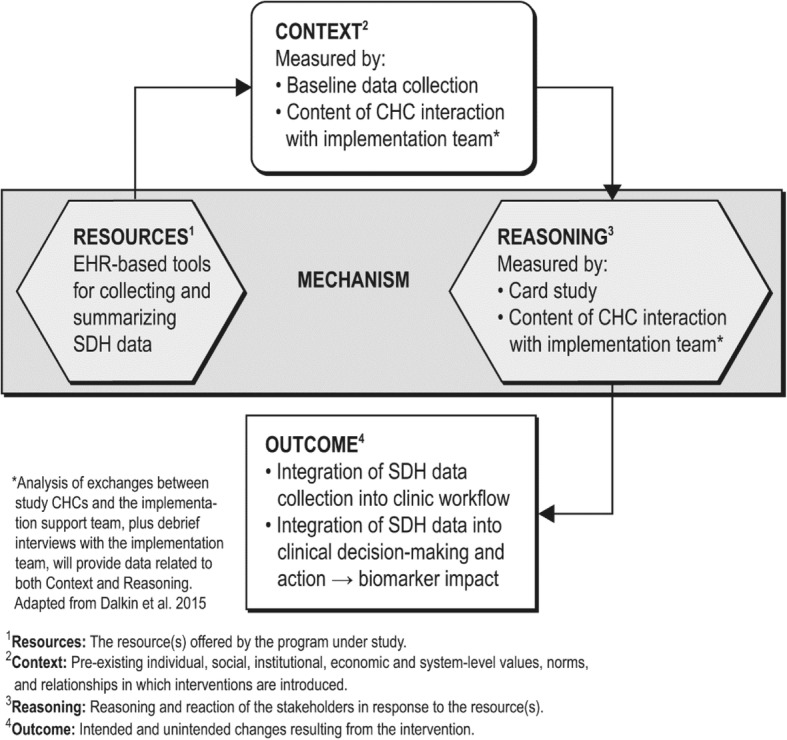

To better incorporate this information into the EHR, providers first must determine how to obtain this information and work it into their clinical workflow. Then they need the technical assistance to support documentation. But all this will be moot if there is not infrastructure further upstream to support these efforts. Coding standards and guidelines will ensure appropriate referral patterns and reimbursement to make addressing social determinants of health sustainable.

Integration into Clinical Workflow

For social determinants of health to be incorporated into the EHR and, therefore, clinical decision-making, providers must first capture this information from patients to understand their individual risks. This requires a large adjustment of clinical workflow.

Providers must first select how they are screening for social determinants of health and which social determinants are addressable.

“What we advise clinics to do is to start small. Maybe pick one social need to screen for,” offered Gold who co-authored a chapter of the National Academies of Science and Engineering and Medicine’s report Integrating Social Care into Medical Care. In the report, Gold and colleagues recommended the first step clinics should take is identifying their goals for screening.

“Why are they doing this screening? What do they want to use this data for,” she asked. “You have to figure out why you’re doing the screening because that will influence what you screen for.”

Once clinics decide on the specific screening tools, they then must consider how they are going to incorporate this information into the patient’s clinical record.

“Some clinics do the screening on paper and then they’ll hand the completed screener to the rooming staff who may enter it then or may enter it later,” Gold explained. “If the data doesn’t get entered in time, it changes whether or not it can be incorporated into the encounter. So, workflow issues are really complicated.”

Streamlining data collection while not over burdening clinic staff is a balance.

“Asking busy staff to collect additional information is burdensome,” said Brian Dixon, PhD, director of public health at Regenstrief Institute and a researcher at the Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health. “If you need to do something rapidly and quick that might not be the best way to do it.”

In light of this challenge, some clinics decide to automatically integrating information on a patient’s social determinants of health into their clinical record using publicly available data.

“We are accessing that information, so we can look at areas of need for our community. When we see patients that live in a certain area, we can assess their needs,” Dixon continued.

Dixon and his team are incorporating information from the Indiana’s Health Information Exchange into patients’ medical records.

“The data are available,” he explained. “They can be fed into the system and trigger responses rather than just asking the frontline staff to collect additional information, which may or may not be of immediate use for that visit.”

But physicians are inundated with pop-up notifications and alerts in their EHR for everything from reminders for medication adherence to screening questionnaires.

“Historically those pop-ups have not been great, so people just ignore them because they’re not accurate or targeted to the patient’s current insurance status,” emphasized Gottlieb.

There is a fine balance between alerting providers to important information and not inundating them with too much information. Figuring out what this looks like for each clinic or hospital requires collaboration between IT and providers in order to understand what will be most useful in the clinical workflow.

IT Support

There is no standard location in the EHR to document social determinants of health. But having a location to document these factors is critical. Providers should have one standard location to understand a patient’s social needs as they have one standard location to look at a patient’s blood pressure.

Without this, providers need to either search through the medical record, losing valuable time with patients, or repeatedly ask patients screening questions. Otherwise, this information cannot be considered in clinical decision-making.

“Social needs must be documented in the EHR. If clinics don’t have a pre-set way to document it, I would at least have them come up with a text shortcut to make documentation easier and somewhat standardize the process,” said Gold.

Building this into an existing EHR infrastructure can be a challenge for many organizations. Those with a rigorous IT department can leverage their internal staff while others might find it beneficial to partner externally with their EHR vendor to build in the capabilities directly.

“If you’re trying to integrate it yourself at an individual clinic level, it’s going to take someone, a dedicated kind of IT resource, to do that. It’s going to be easier to do if you’re a large hospital system and you have a large IT division,” Dixon pointed out.

“Social needs must be documented in the EHR."

So, working closely with the internal or external IT team is critical. Not only will this help set up the infrastructure to document the data, but it will help with external referrals as well.

“There is not a lot of interoperability between clinical organizations and non-healthcare or non-clinical organizations,” Dixon pointed out.

But once social determinants of health are recognized by providers, they want to point their patients to resources to help overcome these challenges.

“One nuance will be how to design interoperable systems across health and social care. How do you seamlessly send patient information to a non-clinical entity and get feedback about whether or not that referral was successful? There are a lot of layers IT needs to fix in order for us to have helpful referral systems,” Gottlieb said.

Building a seamless referral network will be a challenge for providers and payers, requiring standardization and guidelines for referrals and coding.

Upstream Infrastructure: Coding and Standards

While organizations can build a workflow and infrastructure that incorporates patients’ social determinants of health internally, upstream factors in the larger healthcare system must be in place in order for social determinants of health to be sustainably addressed.

One of the biggest factors the industry needs to address is clinical coding. Currently, there are over 1,000 codes to document screening, assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and intervention of social health-related clinical activities. But there is a gap in medical vocabulary and these codes do not encompass every social determinant of health a patient might have.

“The existing medical codes are not that helpful yet. There is no incentive for using them and in many cases. They don’t reflect the social risk screening tools that are in practice right now,” Gottlieb argued.

While many codes exist, they were only used in 2 percent of all inpatient interactions, according to one study.

“Clinicians are not using the codes yet for a complex array of reasons. It boils down to some combination of incentives, availability of interventions, and other roots of behavior change. I don’t think providers are confident yet with asking about how social risks are going to improve care,” furthered Gottlieb.

In order to make coding a more sustainable practice, incentives need to align with the social determinants clinicians are screening for.

“We need to think about incentivizing screening and treatment,” Gottlieb pointed out. “The reimbursement shouldn’t be dependent on whether or not a person is food insecure or we develop a perverse incentive to keep people food insecure. As an example, we now pay health systems for depression screening, not just for patients who have depression.”

Standard reimbursement would promote better screening practices and coding, making addressing social determinants of health more sustainable. Right now, providers are on their own. Each clinic, hospital, or health system is doing things uniquely.

But finding a place for social determinants of health information in the EHR using codes and standards could help providers address some of the most pressing issues for their patients. Enabling providers to easily screen for social determinants of health and use that information at the point of care will make addressing a patient’s food insecurity as streamlined as addressing a patient’s diabetes and place the same importance on a patient’s social determinants of health as their traditional clinical care.