Getty Images/iStockphoto

Digital twin simulation helps baristas make a perfect espresso

A century-old Italian maker of high-end coffee machines used digital twins to virtually eliminate physical prototypes and set the stage for IoT-connected product as a service.

Coffee shop customers probably don't put much thought into the espresso machine the barista uses to make their morning latte, but chances are it's a highly engineered marvel that blends retro design with the digital leading edge. It may well be a LaCimbali or Faema machine from Gruppo Cimbali, an Italian manufacturer that in late 2020 began using digital twin simulation in its engineering process.

"We translate our machines and all the physics behind a cup of coffee into parameters," said Maurizio Tursini, the company's chief product and technology officer. "Then, playing with all these parameters, we can simulate the performance of our machines."

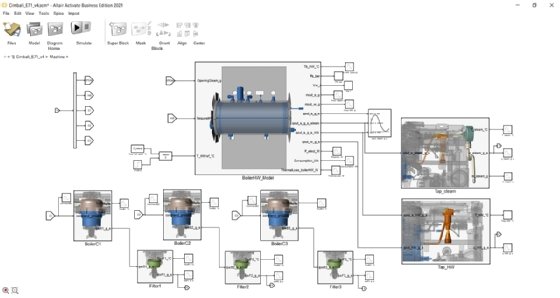

Gruppo Cimbali uses Activate simulation software from Altair, a software vendor based in Troy, Mich., to develop the digital twins. The first was a virtual representation of a baseline coffee machine that has served as the basis for digital twins of specific models, both existing and under development. The software runs on premises under the management of two Gruppo Cimbali employees.

From coal-fired boilers to IoT analytics

Giuseppe Cimbali founded his namesake company in Milan in 1912 to make a variety of copper goods, adding wood- and coal-fired coffee machines with vertical copper boilers in the 1930s. A series of innovations starting in the 1940s and 1950s led to today's highly automated, digitally controlled machines, which require little of the training and experience needed to operate the early units.

First, the introduction of two independent, front-mounted boilers, each with multiple dispensers, improved the ergonomics and production rates because the operator no longer had to move around the espresso machine. Widely available electricity, the invention of the cream-dispensing lever and Gruppo Cimbali's patented hydraulic system brought new levels of automation. The first electronic components arrived in the '80s, and microprocessors came the following decade.

Before adding digital twins, Gruppo Cimbali had long used computer-aided design and product lifecycle management software. There is also machine-to-machine connectivity between what Tursini called "traditional" machines and their attached coffee grinders.

"According to what the grinder is 'understanding,' it is saying to the machine, 'Change this parameter, change the pressure, change the temperature' or vice versa, according to some other parameters in extracting the coffee," he said.

The company claims to be among the first in its industry to add telemetry and data-representation systems to its machines, which are connected to the internet over Wi-Fi. The IoT network collects information about every drink made on a machine and adds it to a database. Analytics on drink quality help users improve their daily management of the machines.

Digital twin simulation virtually eliminates physical tests

As models of physical objects or processes, digital twins don't have to involve simulation to be useful, but digital twin simulation was what Gruppo Cimbali needed.

Christian Kehrer

Christian Kehrer

"They were already using telemetry or IoT and collecting data, but were lacking the simulation part to make it more or less a complete solution," said Christian Kehrer, Altair's business development manager for system modeling. The manufacturer had previously simulated mechanical parts, but not the other important characteristics of an espresso machine, such as heat transfer and water pressure.

"The main focus [of the digital twin simulation] was on evaluating the functional behavior of the multiphysics system, including the thermodynamics, the electrical and the controls," Kehrer said.

Those physics are surprisingly complex. A perfect cup of coffee requires achieving the right balance of water pressure and temperature, which depends on precisely engineering the mechanical parts to help control the thermal exchange between them. The challenge is to do so up to 600 times a day, the capacity of the fully automatic LaCimbali S60, according to Tursini. "The quality must always be the same from cup number one up to cup number 600," he said.

To build the digital twin simulation, Gruppo Cimbali engineers worked closely with Altair's product development engineers and played off each other's strengths. Altair has the engineering expertise, but lacks the domain knowledge about coffee machines that must be encoded in the digital twins, Kehrer said. But its developers could explain the formulas behind the simulations, then ask their counterparts at Gruppo Cimbali to point out what was lacking and fine-tune the models to the company's needs.

The manufacturer was keenly interested in using the digital twin simulation to collect data on energy efficiency, the number of cycles a machine can operate and the temperatures it can achieve.

"That," Kehrer said, "is something that was really new: to be able to evaluate more customer-relevant KPIs in the early stages and to see if I change component A to component B, what is the effect from the customer standpoint? Will it take longer until the machine heats up?" Those parameters translate to how long it takes a customer to get their cup of coffee, which impacts the overall customer experience.

Tursini said that before digital twins, trying out different parameters required a trial-and-error approach. "Using the specification of the model, we defined the parameters, made a prototype and started to optimize. But with a virtual model, we can simulate a lot of configurations so that at the end of the day, the configuration that we decide to use is the optimal one," he said.

As a result, Gruppo Cimbali was able to cut the development time for a new model in its Faema line by 30% to 40%, Tursini said.

Proving the convergence of virtual and physical

Cultural change has been the biggest challenge of implementing digital twins, according to Tursini, who needed to convince engineers accustomed to working with physical prototypes that they could trust a digital twin simulation.

"We made some tests in order to convince them that this was the right approach," he said. "We did physical tests and virtual tests in parallel, and we demonstrated that the results were converging. We demonstrated that this was the right approach [and would also] speed up our time to market."

Tursini said the company would like to implement digital twins in the cloud to make them available to customers by the end of 2022. More accessible digital twins will also help field service technicians analyze information collected on the physical machine against data stored in the cloud. Predictive analytics could help to anticipate service calls and machine failures. The company also plans to eventually offer product as a service, which would take advantage of the IoT connectivity to allow new kinds of services.

Overall, Tursini deems the digital twins a success. "You reduce the time to market, you improve the quality, you have better control over what is happening," he said. "This is something that also helps the engineers do their job better. You have to see this as a support to the engineers' work rather than a substitute."