phive2015 - stock.adobe.com

Blockchain food supply chain growth depends on clean data

Traceability to ensure freshness, safety and compliance is an obvious benefit of blockchain in the food supply chain, but it won't happen without solving data acquisition issues.

The need to trust food supplies is high on the list of priorities for consumers, food retailers and wholesalers, and nations alike. However, tracking and managing the food supply chain from farm to consumer have grown increasingly complicated in a globalized market. The more complex the trail that food follows, the greater the need for accountability at every step to ensure food freshness, safety, and contractual and regulatory compliance. Using blockchain for food supply chain traceability is often touted as the best path to trustworthy food data, but critics say even a blockchain is only as dependable as its weakest links. One of the biggest links is data that is complete and accurate.

"Organizations must make sure that 'clean' data is being inputted into the blockchain and that no integration points are compromised; otherwise, the entire blockchain ecosystem could be compromised," said Maciej Kranz, vice president of the corporate strategic innovation group at Cisco, in an email interview.

Even with IoT sensors and the necessary integrations in place, maintaining just one part of the blockchain may be beyond the skills of many farmers. This is especially true of workers and farmers who most stand to be exploited -- another issue that using blockchain in food supply chains aims to resolve or at least expose.

Blockchain food supply chain data hard to acquire

"Most of the food products in developing economies, like Africa and China, are produced on very small farms that don't have access to technology or internet connectivity," said Nir Kshetri, a professor at University of North Carolina-Greensboro, via email. "Blockchain systems can also be expensive."

"You're really going to set up small coffee farmers in Brazil with IoT devices and assume they'll do their own troubleshooting when stuff inevitably goes wrong?" wrote Dary Merckens, CTO of Gunner Technology, an AWS partner specializing in JavaScript development.

How blockchain works

A blockchain is a decentralized ledger that enables a shared set of computing systems to agree that a transaction between multiple parties is authentic, according to Kranz. It becomes a single source of truth, he said, by virtue of a permanent record wherein each recorded transaction is a block that is tied to the block before it, thus the term blockchain. The ledger is distributed among all transaction participants, thus existing simultaneously in multiple places. This makes it extremely difficult to manipulate entries or tamper with the data undetected.

There are two types of blockchains: public and private, also known as permissionless and permissioned, respectively. Cryptocurrency blockchains are public and permissionless to enable anonymous, public transactions. The food industry uses private, permissioned blockchains, limiting the nodes -- points of data entry and validation -- to trusted entities that are directly involved with that particular supply chain, namely partners, suppliers, distributors, transporters and buyers.

Despite its challenges, evidence of growing and sustained interest in digitized distributed ledgers, aka blockchains, is readily available. Gartner reported that blockchain has been the top search term on its website since January 2017, and blockchain has already made its way into major food providers' supply chains.

Kshetri provided these examples of high-profile blockchain food supply chain deployments in the food and beverage sector:

- IBM Food Trust is being used by large food companies, such as Nestle, Unilever and Walmart. As of June 2018, the system stored data related to 1 million items in about 50 food categories. By July 2018, there were more than 350,000 food data transactions on the platform. Companies of all sizes in the food industry supply chain can join the network for a subscription fee, which ranges from $100 to $10,000 a month.

- Carrefour signed an agreement with IBM to use the Food Trust. The retailer announced a plan to track its own branded products in France, Spain and Brazil and expand to other countries by 2022.

- Subway and Tyson are reported to be testing blockchain systems developed by FoodLogiQ, a provider of technology for traceability, food safety and supply chain transparency.

- In China, e-commerce companies, such as Alibaba and JD.com, have implemented blockchain, mainly for high-value food items.

- Numerous firms in the beverage industry are using or planning to use blockchain, including Swiss Coffee Alliance, Denver coffee roaster Coda Coffee and Dutch startup Moyee Coffee.

Success stories are becoming more plentiful and being used as proofs of concept in food safety and recall management. Walmart demonstrated the potential for blockchain technology by tracing a package of mangos back to the farm from which it originated in just 2.2 seconds, Kranz said. It previously would have taken nearly seven days using traditional methods.

And yet Gartner cautioned: "For all the hype and possibility of blockchain, the technology barely registers as a priority for CIOs … only 5% of CIOs rated blockchain as a game changer for their organization."

Trading partners working on data integration

According to Alex-Paul Manders, a director at Information Services Group (ISG), a research and advisory firm, participants in the beverage and food supply chain are actively collaborating to define and design data structures, business processes and collaboration methodologies. Supply chain vendors are currently evaluating logging data into distributed ledger applications, he said in emailed comments. Track and trace, which pertains to information required to recall a product in the event of a food safety issue, is a prominent use case being addressed, he said.

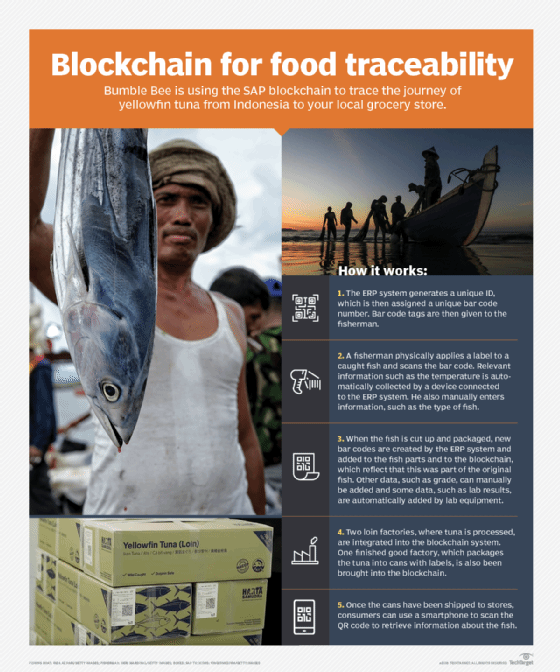

In any blockchain food supply chain use, a unique digital signature is created for each batch of food. The data pertaining to that batch is gathered via RFID, GPS, IoT and related technologies.

"There is always software required between the sensor, human or enterprise ecosystem in front of a blockchain. The data can come from anywhere, but it's likely to be a web interface, [API] or a feed from a system like a manufacturing floor," explained Scott Carlson, head of blockchain security at Kudelski Security, in an email.

"All of these systems need to be integrated into common data formats and be updated to include things like consistent time source or GPS location for measurements. Where no machines or IoT devices are available, it is possible for humans to type in their sample data into a weblike interface and have it stored inside the blockchain," Carlson said.

The collected data can be moved to the blockchain in one of three ways: stored in a database to then be uploaded to the blockchain, moved to the blockchain directly via edge or fog computing devices, or entered directly into the blockchain from the data source.

An example of the latter, Kshetri said, is the Colorado-based Bext360's BextMachine, a Coinstar-like device that employs smart image recognition technology, machine vision, AI, IoT and blockchain to grade and track coffee beans. "It takes a three-dimensional scan of each bean's outer fruit. The information is entered into blockchain," he said.

Standards for blockchain in food supply chain

Ultimately, different blockchain systems have different ways of uploading data since there are no industry standards or firmly established best practices or protocols.

Kshetri cited the example of a blockchain system developed by Chinese e-commerce firm JD.com and Kerchin, a food supplier based in Inner Mongolia. Kerchin collects and stores data in its food supply chain by scanning the barcodes of its products. The information is then entered onto blockchain.

"After that, any changes in data require a digital signature. Both parties are informed if there is any change and modification in the data. JD periodically implements random spot checks at Kerchin's factories to examine the accuracy and validity of information," Kshetri said.

Data siloes typically exist throughout blockchain systems, requiring substantial integration work. Much of the data resides in disparate systems and must be reconciled manually, a tedious process that doesn't address the issues of data consistency and security, according to Kranz.

"Organizations can integrate their private blockchains with IoT devices, ERP systems or other sources of data to automatically record and reconcile this data and share it across enterprises and with their ecosystem of partners and suppliers. Used in this way, a private blockchain can deliver thousands of transactions per second and provide granular management and control on who sees and accesses the transactions," Kranz added.

The goal is to provide an immutable record. But an immutable record does not mean an unchangeable accounting of transactions.

"Just because you write an immutable record that 'carrot 1 is organic' does not mean you cannot write a second transaction that says 'step 4: added chemicals, carrot 1 no longer organic.' You didn't go back and change the first record; you updated the whole chain to gather more information," Carlson said.

While blockchain is regularly touted as providing an immutable record, it does not own that space.

"Blockchains did not invent immutability," said Josh Datko, owner of Cryptotronix, a consultancy in IoT security that frequently works with blockchain companies. "Blockchains are just a data structure, and there are lots of ways to make that immutable. For example, there is this concept of WORM [write once, read many] that existed before blockchains. Skeptics argue that you can get a lot of the same benefits of the blockchain with a WORM database or similar technology," he said.

All of these blockchain problems beg the question of whether the food supply chain really needs blockchain. An international team of researchers who wrote a paper titled "Do you need a blockchain?" found: "In general, using an open or permissioned blockchain only makes sense when multiple mutually mistrusting entities want to interact and change the state of a system and are not willing to agree on an online trusted third party."