Getty Images/iStockphoto

Experts: AI digital humans come with benefits -- and risks

Businesses using AI digital humans in sales and marketing can cut costs through efficiency. However, experts warn of the legal risks and public distrust of the technology.

Listen to this article. This audio was generated by AI.

In the not-so-distant future, the online sales associate or customer service representative who greets you with a warm smile will look human in every way, yet exist only in the digital realm.

Businesses are testing digital humans in websites and business applications for marketing, employee training, and answering questions about products and services. Models trained on only data specific to the task prevent the AI avatars from responding outside the subject matter.

Digital humans offer several business benefits, experts said. They're less expensive than hiring staff to perform the same tasks, they can interact with far more people at once than a single human, and they are particularly suited to meet the needs of B2B customers.

Three-quarters of B2B clients prefer skipping a time-consuming meeting with a sales rep to order supplies, schedule maintenance or discuss product comparisons -- all tasks easily handled by AI avatars, according to Gartner research.

"Part of the drivers around digital humans is not necessarily the technology," said Marty Resnick, an emerging technology expert at the analyst firm. "It's hearing that people want a rep-free experience."

As a result, the analyst firm predicts the percentage of B2B buyers interacting with a digital human during the purchasing process will rise from less than 5% this year to 50% by 2028.

Nevertheless, the use of digital humans does present legal risks, experts said. And companies could face public anger if they hide the use of customer-facing avatars, fail to maintain accuracy in the information they provide and feed the perception that digital humans will replace workers.

In 2023, Mitre, a nonprofit that performs research on behalf of the federal government, found that only 39% of the 2,063 U.S. adults surveyed believed AI technologies were safe and secure, down 9 points from 2022. Fear of losing jobs and media reports of deepfake photos and videos of celebrities contributed to the decline in trust.

Despite the public concern, companies continue to experiment with the technology. Synthesia, one of several startups with online platforms for creating and deploying digital humans, claims 15,000 businesses have generated 4.5 million videos featuring its AI avatars. The company's success has driven its valuation to $1 billion.

"We think that over time, custom avatars will become the norm," said Alexandru Voica, head of corporate affairs and policy at Synthesia.

Other startups competing in the market include Hour One, Touchcast and UneeQ.

Customers of Touchcast's platform for building AI avatars include Australia-based Macquarie Bank, consulting firm Accenture and professors at Imperial College London. The latter uses AI clones to answer student questions anytime during the day or night.

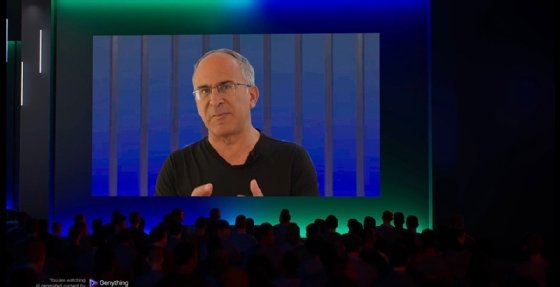

To demonstrate the platform's capabilities, Touchcast CEO Edo Segal had company developers create a digital twin of himself to pitch potential investors and answer their questions. The virtual replica's knowledge base includes product documentation, answers to questions typically asked by potential investors, and a brief overview of the company's business plan, products, services and growth potential.

"It's literally part of our fundraising playbook," Segal said of his digital clone.

Legal considerations

Whether pursuing the cutting edge, like Segal, or more modest uses of AI avatars, companies must consider their legal responsibilities, corporate lawyers said.

Courts are unlikely to treat digital humans differently than other forms of communication between companies, customers and partners. Enterprises are responsible for everything the avatar says, so they should establish strict guidelines for the use of the technology.

"You have a lot of companies kicking and screaming and scratching to make money and make profits and have very aggressive salespeople," said Chanley T. Howell, a partner at law firm Foley & Lardner LLP. "With aggressive sales tactics, you could certainly have some misleading statements and use cases."

Foley & Lardner advises clients to require AI suppliers to cooperate in a lawsuit, investigation or enforcement action by a regulator. A court might require the maker of a company's digital human to cooperate. Still, the process is much faster and easier with a contractual obligation.

However, getting an AI vendor to agree to such a stipulation might prove difficult, Howell said.

"The bigger the deal, the more likely the AI vendor will say, 'OK, we don't like this, but we'll do it to get the deal done,'" he said. "But the initial reaction is a hard no."

The legal challenges have led some Foley clients to skip AI cloning, even if it's only an executive's voice, Howell said. In one case, a Foley client dropped plans to clone the voices of the CEO and other executives for messages sent to employees.

"Even if they trusted the vendor, the risks of that getting out or something going wrong outweighed the benefits," Howell said.

People's fears, concerns with AI clones

The digital humans used in business today lack sophistication in look and movement to fool most people into believing they're real. However, AI startups hope to change that to make their fake humans more effective in interacting with people.

"It's going to take a few years before we get to 100% realistic avatars that can do everything a human can do on command," said Steffen Tjerrild, COO and CFO at Synthesia. "But this is the path we're going down for sure."

That pursuit of realism will increase the likelihood of raising people's fear of AI cloning, according to research. Participants in a study conducted by scientists from the University of British Columbia and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology expressed concerns that digital replicas of people threatened personal identity and could become a substitute for human interaction.

"They speculated that AI clones could turn individuals into transactional products for someone else's profit and pleasure, overstepping moral boundaries of identity," the study said.

Participants were skeptical that there would be mechanisms in place to guarantee an individual's consent and control.

Participants in the empirical study -- a research method that collects data through direct observation or interviews -- were 20 adults ranging from ages 19 to 70-plus. Their occupations included research technicians, students, entrepreneurs, realtors, teachers, software engineers, landscapers and retirees.

Segal's digital clone has been well received by people who have interacted with it, the Touchcast CEO said. However, he acknowledged that AI digital clones indistinguishable from humans could one day lead to unforeseen problems.

"We have this new medium of communication that we need to grapple with and wrap our minds around, and figure out how to do it responsibly," Segal said.

In the meantime, businesses experimenting with digital humans today should monitor carefully for public acceptance, a critical component to achieving a return on investment, according to Gartner.

"As long as digital humans are transforming humanity for the better and [there's] trusted transparency, it should be successful," Resnick said.

Antone Gonsalves is an editor at large for TechTarget Editorial, reporting on industry trends critical to enterprise tech buyers. He has worked in tech journalism for 25 years and is based in San Francisco. Have a news tip? Please drop him an email.