Sergey Nivens - Fotolia

How to build a world-class customer experience system, part 2

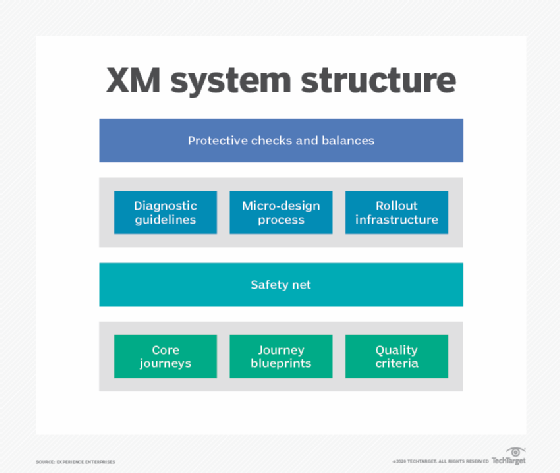

Building off the previously discussed foundation, Megan Burns explains what's needed to complete an XM system: diagnostic guidelines, micro-design process and rollout infrastructure.

A few weeks ago, I explained why organizations need to a system to manage customer experience and the four building blocks that make up its foundation. In case you need a reminder, they were:

- A list of five to seven customer journeys that you will manage with the most care.

- A set of blueprints showing how each of those journeys should

- A list of criteria that define experience quality for you so people know what matters.

- A safety net -- the follow-up and recovery process that sparks someone to reach out to customers who had a bad experience and try to make things right.

Here, I'll explain the components of an XM system that will sit atop this foundation. The experience management system exists to stem the flow of problematic experiences so there is less for your safety net to catch.

The best apology is changed behavior

Reacting to problems after the fact is not management -- it's damage control. As Albert Einstein said, "A clever person solves a problem. A wise person prevents it." How do you prevent customer experience problems? One way is to see where those problems were introduced into the process and update the source so the same thing doesn't happen to anyone else. Components 5, 6 and 7 of the XM System -- diagnostic guidelines, a micro-design process and a rollout infrastructure -- define how you'll do it.

Diagnostic guidelines: Make sure you're solving the right problem

Doctors go to school for years to learn the diagnostic process because the body is a complex system. Most symptoms have hundreds of potential causes. Treating the wrong illness is at best a waste of time and money. Worst-case scenario, it's deadly. Experience ecosystems aren't as complicated, but they aren't simple, either. I've seen millions of dollars wasted on "fixes" that don't end up fixing anything.

Good XM systems mitigate this risk with diagnostic tools. The simplest version of this is a checklist of "things to think about" before you start changing journeys. Here are a few of my favorites:

- Do you really need to change the design or just help people execute the current design more consistently?

- Does this happen because of something you can't control or is it a self-inflicted wound (e.g., you put key info in a place your customers would never look)?

- If this journey involves multiple teams, what's the handoff process? Do people understand what has to happen before and after they step in to make the whole thing work?

Questions like these make people think beyond their surface-level understanding of any issue to second- and third-order causes. The only hard and fast rule I give people when it comes to diagnosing experience issues is this -- never, never say the cause of an issue is the customer. If someone argues that "the customer misunderstood," push them one step further. If a customer misunderstands it's because the company wasn't clear enough.

Micro-design: Everything is better when you involve customers

The path from problem to solution lies in the design process, but most companies only use a formal design process for big projects like a new product or website redesign. That's a problem because big projects are few and far between. The only way to avoid chipping away at the integrity of the end-to-end experience is with a micro-design process. What's that? It's a lightweight version of your full design process that anyone can use to validate or correct their proposal for smaller changes before moving on to implementation.

Micro-design should enable best practices like co-creation, prototyping and iterative testing, just on a smaller, faster scale. Rather than convene a big study for every project, for example, many companies are establishing a community or customer advisory board. That gives employees access to a steady stream of customers who can provide feedback and test concepts any time. One of my clients went even further, creating a design toolkit for non-designers. It gave associates access to a simple version of the tools the design team used to do things like storyboard, mock up interfaces or collect remote feedback. They weren't trying to make everyone a design expert, just help them do whatever job they already have in a design-literate way.

Rollout: Don't just tell people, help them remember

You've got a new design. Great! Now what? Ideally, you aren't answering this question from scratch every time. A Master Rollout Plan captures in advance the list of channels and strategies people can use to launch an experience change at scale. It describes best practices for when, where and how to teach employees what they need to know and do given the kind of change you are making. It also spells out how to reinforce new routines over and over until they become habit. People need to hear and do new things many, many times before they sink in, but project teams often want to send a few emails and run a training class and be done. The rollout plan makes it clear that this isn't an option.

Thankfully, reinforcement doesn't have to be expensive or formal. I tell leaders I work with to ask questions about a change in every meeting they go to for at least a month. I'm not saying give people pop quizzes; they should be curiosity-driven questions like: "What are you hearing from customers about the new policy?" or "How does the approach you're suggesting fit in with the new process for x, y and z?" To answer these questions, people will need to bring details of the new design to the front of their mind. The more often we recall information consciously the more quickly and deeply it replaces old data in long-term memory.

Build a force field to block unintended consequences

Everything we've talked about so far assumes you are intentionally trying to boost CX. Often, though, experience quality is driven by side effects from non-CX work like cost-cutting programs and regulatory compliance. People who lead those projects rarely see themselves as CX designers so they aren't in the habit of thinking through the ripple effect their decisions will have on customer journeys. The final piece of the customer experience management system -- a layer of protective checks and balances -- exists to build that habit and avoid the damage that's so often done because we don't know what we don't know.

This layer of XM governance trips many people up because it's hard to draw a box around. It is a set of checks and balances embedded into every business process in every corner of the organization. If you have a CX team, they aren't in charge of these activities. They rely on people who run existing budget planning, risk management and IT governance flows to make sure CX has a (conceptual) seat at every table. For example, the quarterly planning process should check to see which projects on the docket might impact the same journey so they can be coordinated. Risk assessments should include the risks an action (or inaction) may pose to CX or loyalty. Governance processes in groups like IT and HR should provide a framework for thinking through how a back-end decision will ripple through to customers. This doesn't mean you say no to any decision that customers may not like. It just means you make those decisions fully aware of and prepared for the impact they will have on customer interactions. In the end, intentional decision-making is what the whole process of experience management is all about.

About the author

Megan Burns is an experience strategist, keynote speaker and thought leader who helps Fortune 500 companies use customer experience as a path to profitable growth. Most people know Megan from her decade at Forrester Research where she built the Customer Experience Maturity Model and The Customer Experience Index 2.0 along with over 70 reports on leadership, culture and governance. Megan is a trusted advisor to customer-centric executives around the world, including more than half of the Fortune 500 companies. When she's not working, Megan loves reading, watching documentaries and exploring historic places in Greater Boston where she lives.