Generative AI tools are here, but who's using them?

Generative AI has much promise. But the road between here and delivering on those promises looks to be a lot longer than when ChatGPT first dropped in November 2022.

Much of the positive noise around generative AI tools is made by tech vendors. When their hopes and dreams are reality-checked with actual customers and analysts, that's all they seem to be: hopes and dreams.

Tech companies rewrote product roadmaps overnight early last year to include GenAI. Now those products are rolling out, the bills are coming due for all that dev work and all those AI tokens spent since OpenAI released ChatGPT in November 2022. Nothing comes for free.

Microsoft will discontinue its free GPT Builder in Copilot Pro on July 10-14, removing customers' existing GPTs and deleting the data from them. Goodbye. Published reports say that as Microsoft considers how to recoup its massive investment in OpenAI, there might be an AI-laden Microsoft Office "E7" license to come later this year to go with enterprise E3 and more feature-rich E5 licenses.

Yet few customers are paying for generative AI, according to empirical evidence shared by analysts and customers. It's one thing to evaluate free generative AI tools, assemble a cross-functional team to evaluate its potential and pilot the technology during a trial period. It's quite another thing to pay for it.

IT leaders worry about surprise AI consumption bills, along the lines of U.S. patients worrying about surprise medical bills. End users don't necessarily see the benefits of AI writing tools when results are far enough off that they must rewrite, for example, an AI-generated email for their job.

Deep Analysis founder Alan Pelz-Sharpe said that 15 integrators with whom he discussed generative AI last week told him that few of their customers are using or buying generative AI.

"While lots of people are fiddling around with it, nobody -- like, nobody -- is using it [in production]" outside of some bold early-adopters, Pelz-Sharpe said.

Deployment still a work in process

Part of the reason people find it hard to use generative AI tools is trust. Fair or not, they think the technology is coming after their jobs. Real anxiety exists among the people who are supposed to use it.

In a research report published earlier this year, Valoir found that workaday office users don't even like the word "copilot," because it sounds like a peer. People like "AI assistant" a lot better, because that sounds a lot less intimidating -- and competitive.

Another reason people don't trust generative AI, Valoir founder Rebecca Wettemann said, is that OpenAI's first releases of ChatGPT had a number of issues, such as inaccuracies and hallucinations. While the world helped train OpenAI's first public large language models on a massive scale -- and things improved quickly – early users had a bad experience.

"ChatGPT was iffy in the beginning," Wettemann said. "Some people kicked the tires on early versions of it [and associated Microsoft products] and said, 'Boy, I would never trust this.'"

Today, generative AI tools have matured but still have room for improvement. Take the example of Siri, whose natural language processing can only manage a few chunks of sentences without context. Apple Intelligence, the new generative AI the company has begun to embed in its systems including Siri, promises to improve the quality of its output.

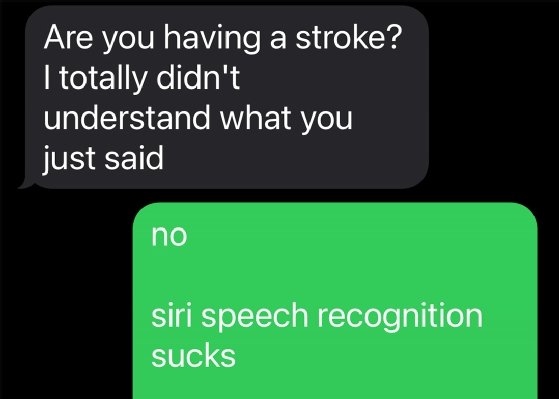

Right now, Siri users must be her human in the loop. I recently was reminded what happens when you don't check Siri's output before hitting "send." I was texting a friend who is a speech pathologist, and Siri said such gibberish that it alarmed her. She asked if I was having a stroke. Think about that: An actual speech pathologist, whose job it is to consider how humans communicate, graded Siri's speech-to-text as a "possible stroke." Yeesh.

Image recognition also seems to be a problem. In discussing this strain of generative AI with a content manager for a famous brand of ice cream found in most U.S. grocery stores, she told me it's not ready for prime time. They can't train the tools they've evaluated to get even close to auto-populating images with the specific metadata the company's designers must manually enter for every graphics file they create. The company, she said, will probably try again in a few years.

This is where we are with generative AI today. Tomorrow will be better as the technology improves, the AI gets smarter and we get used to using it.

Don't write off generative AI just yet

A longtime AI developer and skeptic is Pegasystems CEO Alan Trefler. In a quiet interview moment prior to the pandemic, Trefler, who started working on AI since the 1970s at Dartmouth College, confessed that "AI" as it was then constructed is a mere marketing term we as an industry had informally agreed to call machine learning, analytics and natural language processing in aggregate. It sounds good. But it's not actual AI.

At the time, Trefler went on to say that he wouldn't consider a technology as AI until it's sentient. Then he stopped, knowing he'd worsen the flogging he'd earned from his public-relations and marketing staff by saying what he already had.

I revisited that question last month while discussing Blueprint and other PegaWorld Inspire generative AI releases. While mum on the "sentient" part, Trefler said he sees generative AI as perhaps the biggest leap forward ever in so-called "AI." His first encounter with OpenAI's ChatGPT was on a YouTube video demo. Then he got his hands on it.

"When I saw the video, my original reaction was, 'Is this real?'" Trefler said. "I very quickly got access to it. My second reaction was, 'This is so much better than I would have imagined possible three years ago.'"

Pegasystems will build its AI systems assuming there will always be humans in the loop to guide them, Trefler said. He and other tech leaders have staked huge financial bets that generative AI will eventually be widely adopted. So, while it's not quite happening yet, many tech vendors believe the time will come.

His peers working on autonomous Artificial General AI systems, Trefler believes, are building something "disastrous," especially for companies whose users are in regulated industries.

But deployed in the right way, generative AI has a bright future, regardless of current adoption numbers.

"I've always believed that people had some special magic -- tied to our humanity and our ability to use language -- that the machines could never recreate," Trefler said. "Maybe it turns out that all you need is 1.7 trillion connections. Maybe it turns out machines could do it. It's very sobering. It has very interesting ramifications because when you play with [generative AI] enough -- and we play with it all the time -- yeah, it's wrong sometimes, and it has problems. But what it does is actually magical -- more than I would have ever expected."

Don Fluckinger is a senior news writer for TechTarget Editorial. He covers customer experience, digital experience management and end-user computing. Got a tip? Email him.