Rawpixel - Fotolia

Myth or emerging trend? Cloud repatriation explained

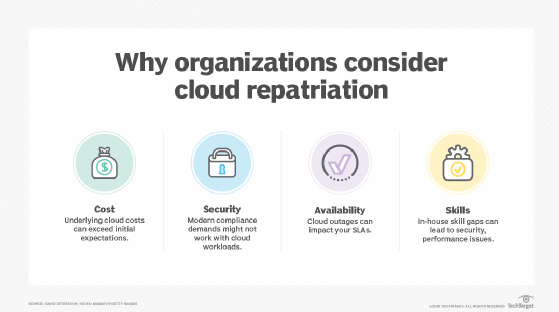

Cloud customers may look to move workloads off the public cloud because of cost, security, availability and staff skill sets. But how common is the move itself?

Cloud repatriation is a tricky topic -- some say it never happens, while others claim it's a rising trend. Both are somewhat true. Many organizations consider repatriating cloud workloads at some point, but few ultimately make the move. Still, cloud repatriation has a role in modern IT, mostly as a contingency plan in your IT playbook.

The idea of computing as a utility has been around since the inception of the internet. In the decades that followed, public cloud computing emerged to fulfill the basic promises of utility computing -- ready access to vast computing and storage resources, plus a bevy of powerful services, all of which are available on-demand under a consumption-based pricing model.

And the public cloud has become enormously successful. Organizations of all sizes strategically deploy workloads and store data within a provider's vast global infrastructure, minimizing the capital investment and overhead associated with traditional data centers. But the public cloud is not perfect.

The idea of cloud repatriation has some validity. The successful adoption of utility computing is far more complicated than inserting a plug into a receptacle. Not all workloads can, or even should, be migrated to a public cloud. And when results fall short of expectations, the business faces the troublesome prospect of what we call repatriating the workload back to the local data center. IDC research from 2019 reveals that 85% of survey respondents considered some form of repatriation, though this doesn't mean they actually made the move.

The realities of cloud repatriation

Although many public cloud users consider cloud repatriation, most organizations will not actually need to do it. Gartner survey results from a 2019 report, titled "Define and understand new cloud terms to succeed in the new cloud era," indicate that roughly 21% of 134 respondents had repatriated workloads, but only about 4% repatriated workloads from a public cloud provider. The remainder had repatriated from colocation, SaaS or other outside services.

"If a workload or project is not delivering desired results, it may make sense to move that workload," said David Mitchell Smith, distinguished VP analyst at Gartner. "Note that this is a workload-by-workload decision, not an overall mega strategy. So it can be realistic for that workload, but it really depends."

An organization typically repatriates due to dissatisfaction with an outside vendor, Smith said. Or it doesn't want to extensively use public cloud or colocation resources for development and test workloads anymore -- workloads that were never really intended to live permanently in the cloud anyway.

Generally, the business may realize that not every workload should exist in the cloud. Still, cloud repatriation is an exception and not the rule, he said.

And repatriating a workload effectively is often far easier said than done.

Repatriation can be relatively quick and painless when cloud providers and customers share common stacks. Pete Sclafani, COO and co-founder of 6connect, a network provisioning and automation company, cites one anecdote where a customer ran VMware locally while using VMware on AWS. If you need to move a workload, it's easy in this case to shift from cloud to local environments.

Conversely, it will be a greater challenge for a business that has fully transitioned to a cloud-native model where IT is mainly about managing service. It may find that the infrastructure -- and skill set -- can't be repatriated effectively.

Newer platforms such as Kubernetes for container orchestration and automation can sometimes help, especially compared to VMs, which have greater dependencies. Thus, if your cloud and local environment both use Kubernetes, you could potentially have an easier migration.

Have repatriation in the IT playbook

Ultimately, cloud repatriation is still a prudent part of contingency planning. Most businesses won't need to repatriate workloads that have been properly architected and optimized for deployment in the public cloud. But you should know how to approach a repatriation and execute such a move if the need arises.

Such contingencies aren't necessarily due to oversights or mistakes upfront, but rather from the incalculable impact of future change as the public cloud industry continues to mature and evolve, Sclafani said.

"Say database writes go up in price and now you need to optimize your application or else your costs skyrocket beyond your budget," Sclafani said. "The challenge is how to architect your workloads in such a way that they can be shifted between a public and private cloud."

Organizations must remember that cloud providers are independent businesses designed to generate revenue for cloud providers. Users must always be ready for that partnership to shift.

Why repatriate cloud workloads

There are four principal factors that drive organizations to consider moving a cloud deployment back to the local data center: cost, security, availability and skills. Organizations should build their contingencies around these issues.

Cost

The basic premise of public cloud is that it's cheaper to use someone else's utility than to build and operate one yourself. With the public cloud, a business can generally forego the capital expenses and ongoing maintenance of owning and operating a data center.

However, in practice, cloud costs for a workload can involve a bewildering number of related resources. This can include server instances, storage volumes, per-use service and other component costs that are not apparent when planning a workload deployment to the public cloud. The cost for complex cloud workloads may exceed expectations, especially if the workload's utilization or underlying service costs change over time.

"Cloud can be expensive and there definitely comes a time when the intersection of cost and performance is in direct conflict with your budget," Sclafani said. "The challenge is that this is heavily dependent on the cloud provider, your application architecture and traffic/usage pattern."

Security

From a technological standpoint, the public cloud is not inherently less secure than a private data center. When data leaks or improper access occurs, the cause is often traced to inadequate configuration and precaution on the part of the cloud user.

Still, some companies realize this too late. And some critical workloads may not work for the cloud, given the nature of remote access, granular access control within the public cloud and the additional security demands of modern corporate and regulatory compliance.

"There are quite a few reporting requirements, and hosting data elsewhere [in the public cloud] just requires many more steps to verify," Sclafani said. "If data is locally stored, even in a public cloud pod, you still end up with a greater level of physical control, which is a paramount element of any security strategy."

Availability

Public clouds are certainly not immune to outages. Though increasingly rare, cloud outages can potentially last for days and impact thousands of customers. In these cases, cloud customers are at the mercy of the provider, which must allocate resources and direct remediation efforts -- sometimes while the businesses' own service-level agreements are affected.

On the other hand, with a local workload, the business has full control over the availability and performance of the application. In-house IT staff that is suited to the workload's requirements can address and correct problems. In some cases, workloads may be run concurrently -- i.e., both in the cloud and locally -- to provide better performance and a measure of resilience that public clouds alone might not accommodate.

Skills

Cloud workloads demand a specific skill set. An organization's staff will need to adjust -- from provisioning cloud infrastructure to reporting on performance. Businesses that embrace the public cloud must equip IT staff with a broad array of cloud architecture and IaaS skills that may not be needed with traditional in-house IT. Skills gaps can lead to security oversights, performance problems and other workload limitations which necessitate the workload's return to the local data center.