peshkova - Fotolia

RM principles should guide compliance management system development

Regulatory agencies offer broad guidance for compliance management system development, but companies may be best served by referring to widely accepted risk management principles.

An effective compliance management system allows organizations to pinpoint where legal and regulatory risks are greatest. This knowledge helps the institution direct its limited compliance resources to where they will have the most impact and helps make informed decisions regarding which business activities should be expanded, contracted or terminated.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has generated acute awareness of the term compliance management system (CMS) since it started issuing its highly publicized consent orders in 2011. In these orders, the CFPB has invariably cited "significant weaknesses" in the subject party's CMS, along with violations of specific federal consumer financial laws. The CFPB's ubiquitous citing of CMS-related deficiencies against entities engaged in credit card lending, mortgage lending, auto lending, payday lending, check cashing services, payment processing, collections and other financial activities begs the question of whether any business is capable of meeting the CFPB's expectations.

The CFPB's primary guidance regarding CMS expectations is found in its "Supervision and Examination Manual" issued in October 2012. The manual's discussion of CMS is influenced by earlier guidance issued by federal banking agencies and, in many cases, is nearly identical.

Supervisory expectations for CMS are consistent across different agencies and draw upon globally accepted principles for safe and sound risk management (RM). The "Comptroller's Handbook for Compliance Management System," which was published by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in 1996, refers to a CMS as "the method by which the bank manages the entire consumer compliance process." Guidance issued by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in 2006, in turn, spoke of "a sound compliance management system that is integrated into the overall risk management strategy of the institution." Both of these descriptions encompass more than just the compliance business function, which is what first comes to mind when most people hear the term compliance management system. The compliance function is certainly a component of a CMS, which is best described as an overarching risk management structure for ensuring firm-wide compliance with legal and regulatory requirements.

The intersection of compliance and risk

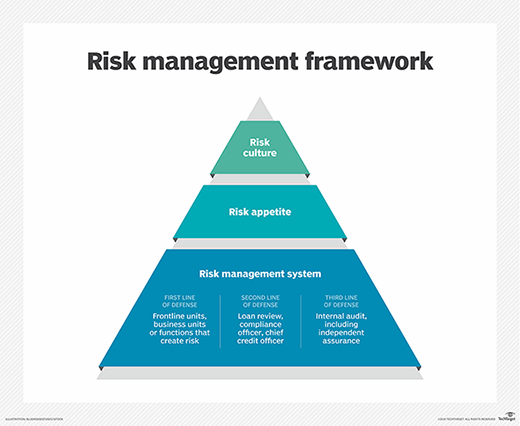

The "Comptroller's Handbook for Corporate and Risk Governance" discusses supervisory expectations for a financial institution's enterprise-wide risk management system and includes the following illustration:

It is a universal principal of sound risk management that the board of directors, or its equivalent in smaller entities, sets the "tone from the top." To this end, the CFPB manual emphasizes the need for the board and senior management to set "clear expectations about compliance, not only within the entity, but also to service providers."

The CFPB manual states that an effective CMS should include:

- Board and management oversight;

- Compliance program;

- Response to consumer complaints; and

- Compliance audit capabilities.

Comparable guidance has been issued by federal banking agencies that refer to an institution's "risk appetite" and its "risk appetite framework." Risk appetite refers to an institution's tolerance for the financial costs resulting from failures to comply with business or regulatory requirements. These concepts are also addressed in guidance issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which has a strong influence on global financial regulators. In particular, Basel guidance recommends adopting a formal statement of risk appetite that takes into account the impacts of potential failures in regards to earnings, capital, liquidity and other financial components.

The CFPB manual and similar agency guidance all make reference to a "three line of defense" risk management system. Under this structure, the responsibility for day-to-day adherence to the institution's operational policies and procedures lies with the organization's front line business units; i.e., the first line of defense. The second line of defense functions, which include the compliance function, are responsible for monitoring and testing to validate the effectiveness that the first line of defense-managed controls have in mitigating applicable risks. Finally, the third line of defense, which typically is filled by internal audit but may be conducted by an external audit firm, performs testing to validate the effectiveness of the first and second lines of defense to maintain compliance.

In all relevant agency guidance, irrespective of the particular agency, the compliance function is expected to be independent from the first line of defense. Typically, this independence is achieved by establishing a separate compliance unit, but the CFPB manual acknowledges that "compliance will likely be managed differently by large banking organizations with complex compliance profiles and a wide range of consumer products, financial products and services at one end of the spectrum, than by entities that may be owned by a single individual." With respect to smaller entities, the manual notes that "a full-time compliance officer may not be needed" and suggests that independence may be achieved through the segregation of duties. Similarly, guidance issued by the FDIC provides that:

[T]he formality of the compliance program is not as important as its effectiveness. This is especially true for small institutions where the program may not be in writing, but an effective monitoring system has been established that ensures overall compliance.

All relevant agency guidance is also in accord with respect to specific expectations for the compliance function. The CFPB manual states a general expectation, which is closely mirrored in other guidance that every supervised party, with the exception of very small parties, will "establish a formal, written compliance program … [which] should be administered by a chief compliance officer."

In addition, the CFPB manual emphasizes the importance of managing consumer complaints, which is described as an essential component of an effective compliance management system. This strong emphasis on complaints management reflects the CFPB's targeted mission to protect consumers from financial harms.

The benefits of incorporating RM principles

Returning to the threshold question of whether any supervised party is capable of meeting the CFPB's expectations for CMS, the short answer is yes. In its summer 2013 "Supervisory Highlights," which included a section devoted to expectations for CMS, the CFPB noted that the "majority of banks examined by the CFPB have generally had an adequate compliance management system structure; however, several institutions lacked one or more of the components of an effective CMS." In the case of nonbanks, however, the same discussion noted that some entities had no CMS structure, while others attempted to embed compliance within the business line, which the CFPB noted can lead to problems. In sum, for any entity that is subject to CFPB oversight, irrespective of size, knowledge of generally accepted risk management principles can prove invaluable in avoiding and, if necessary, successfully remediating CMS-related deficiencies.

Lastly, the reason why CMS-related deficiencies appear in nearly every CFPB consent order, including those levied against banks, can be explained by reviewing the following statement from the CFPB manual: "A well planned, implemented, and maintained compliance program will prevent or reduce regulatory violations, protect consumers from non-compliance and associated harms, and help align business strategies with outcomes." Logically, if laws and regulations were violated enough to cause substantial financial harm to a significant numbers of consumers, the supervised party's CMS must have failed in some respect.

If weaknesses in a supervised party's compliance management system are found by CFPB examiners, that party will be called upon to explain why:

- isolated deficiencies in its CMS did not contribute to violations of law (i.e., CMS-related deficiencies are typically only cited if violations of law occurred); and

- its overall CMS should be considered appropriately structured and well managed.

Based on CFPB consent orders issued to date, the chances that the first explanation will be accepted are exceedingly slim. However, the second explanation should prove successful if the supervised party's CMS reflects accepted risk management principles.

About the author

Mark T. Dabertin is special counsel in the Financial Services Practice Group of Pepper Hamilton LLP. He has over 25 years of broad-based experience in financial services law and consumer and regulatory compliance.