What is public cloud? A definition and in-depth guide

A public cloud is a third-party managed platform that uses the standard cloud computing model to make resources, applications and services available on demand to remote users around the world. Public cloud resources typically include conventional IT infrastructure elements, such as VMs, containers, serverless instances, applications and storage.

Services can include an array of workloads, including databases, firewalls, load balancers, management tools and other PaaS or SaaS elements. Users then assemble resources and services to build an infrastructure capable of deploying and operating enterprise workloads. Public cloud services can be free or offered through a variety of subscription or on-demand pricing schemes, including pay-per-usage or pay-as-you-go (PAYG) models. Extended-use models can typically qualify for pricing discounts, such as committed-use discounts, reserved instances or savings plans.

Public cloud provides the following primary benefits:

- A reduced need for businesses to invest in and maintain their own on-premises IT resources.

- Scalability to quickly meet workload and user demands.

- Fewer wasted resources, as businesses only pay for what they use.

This comprehensive guide examines all aspects of public cloud, including benefits, challenges, technologies and trends. Readers will also get a big-picture analysis of what businesses must do to comply with proliferating local, national and regional data privacy, protection and sovereignty laws. Hyperlinks presented throughout this page connect to related articles that provide additional insights, new developments and advice from industry experts critical to planning, building, implementing and managing a successful public cloud strategy.

How does public cloud work?

A public cloud -- an omnipresent virtual place for hosting platforms, services and applications -- is an alternative deployment approach to traditional on-premises IT architectures. In the basic public cloud computing model, a third-party provider hosts scalable, on-demand IT resources and delivers them to users over a network connection through the public internet or a dedicated network. Public cloud computing is often viewed as utility computing, in which computing capabilities are delivered to users on demand, just as any other utility, such as water, gas and telecommunications.

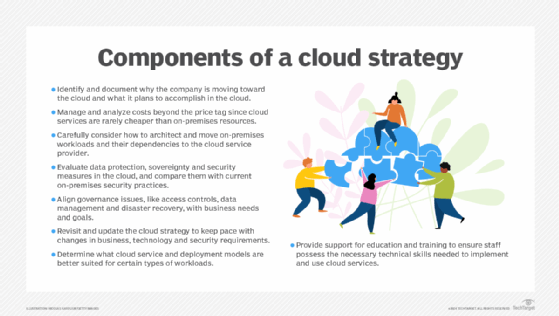

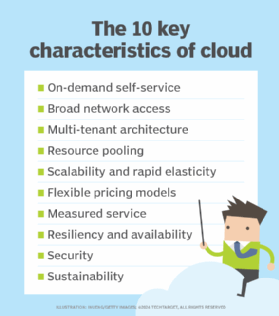

The public cloud model encompasses many different technologies, capabilities and features. At its core, however, a public cloud consists of several key characteristics:

- On-demand computing and self-service provisioning with high levels of automation.

- Multi-tenant architecture.

- Broad network access.

- Scalability and rapid elasticity.

- Resiliency and availability.

- Resource pooling.

- Sustainability.

- Pay-per-use pricing with discounts available.

- Measured service.

- Security using a shared responsibility security paradigm.

The public cloud provider supplies the infrastructure needed to host and deploy workloads in the cloud. It also offers tools and services to help customers manage cloud applications, including data storage, security and various monitoring and reporting capabilities.

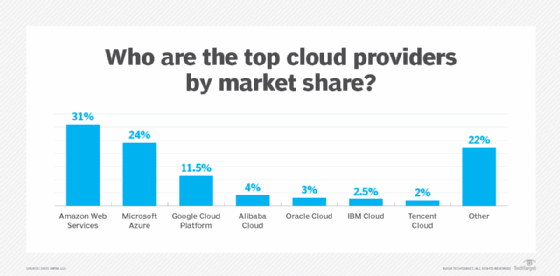

When selecting a cloud service provider (CSP), businesses can opt for a large general-use provider, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud Platform (GCP), or a smaller provider, like Alibaba Cloud, Salesforce, IBM Cloud, Oracle Cloud and Tencent Cloud. General cloud providers offer broad availability and integration options and are desirable for multipurpose cloud tasks. Niche providers offer more customization or focus on specific cloud capabilities.

Migration to public cloud

Myriad factors drive businesses to migrate from on-premises facilities to public cloud. Some businesses, for example, require support for more diverse workload types that data centers can't provide, while other companies might need scalability for tasks like big data analytics that current on-premises IT infrastructure can't handle. Cost considerations, less overhead, lower direct maintenance and readily available redundancy options are other common reasons to vacate the premises and migrate to the cloud.

After choosing a provider, the IT team must select a cloud migration method to move data and workloads into the CSP's cloud. Offline migration requires IT teams to copy local data onto a portable device and physically transport that hardware to the cloud provider. Online data migration occurs via a network connection over the public internet or a CSP's networking service.

When the amount of data to transfer is significant, offline migration is typically faster and less expensive. Online migration is a good fit for organizations that don't move high volumes of data.

Businesses also can onboard existing on-premises applications into the cloud using different approaches, including the following:

- Move the application to the cloud as is without redesign -- a fast approach known as a lift-and-shift that's subject to performance and cost issues.

- Refactor on-premises applications ahead of the migration, which takes IT teams more time and planning but ensures the applications will function effectively in the cloud.

- Redesign and rebuild the software entirely as a cloud-native application.

Regardless of the migration approach selected, a range of cloud-native and third-party migration tools, including AWS Application Migration Service and AWS Migration Evaluator, can help manage the move to a public cloud.

Public cloud architecture

A public cloud is a fully virtualized environment that relies on high-bandwidth network connectivity to access resources and exchange data. CSPs use a multi-tenant architecture that enables users -- or tenants -- to run workloads on shared infrastructure and use the same physical computing resources. Each tenant's data and workloads in a public cloud are logically separated and remain isolated from the data of other tenants through virtualization technologies.

CSPs operate cloud services in logically isolated locations within public cloud regions. These locations, called availability zones, typically consist of two or more connected, highly available physical data centers. Businesses select availability zones based on compliance and proximity to end users. Cloud resources can be replicated across multiple availability zones for redundancy and protection against outages.

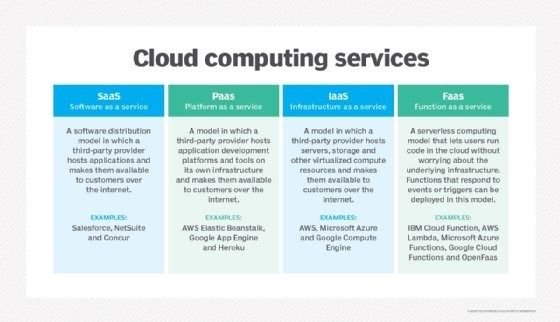

Public cloud architecture can be further categorized by service model. The following are the three most common service models:

- IaaS. A third-party provider hosts infrastructure components, such as servers and storage, as well as a virtualization layer. The IaaS provider offers virtualized computing resources, such as VMs, over the internet or through dedicated connections.

- PaaS. A third-party provider delivers hardware and software tools as a service to its users -- usually needed for application development, including OSes.

- SaaS. A third-party provider hosts applications and makes them available to customers over the internet.

The service model determines the amount of control businesses have over certain aspects of the cloud. In IaaS deployments, for example, cloud customers create VMs, install OSes and manage cloud networking configurations. But in PaaS and SaaS models, the CSP fully manages the cloud networking architecture.

Another service model, function as a service (FaaS), further abstracts cloud infrastructure and resources. It's based on serverless computing, a mechanism that breaks workloads into small, event-driven resource components and runs the code without deliberately creating and managing VMs. Businesses can execute code-based tasks on demand when trigged. The components exist only as long as the assigned task runs. As with all other cloud models, the provider handles the underlying cloud server maintenance.

Businesses also can opt for a storage-as-a-service provider in public cloud. The provider delivers a storage platform with offerings such as bare-metal storage capacity, object storage, file storage, block storage and storage applications like backup and archiving.

Public cloud automation

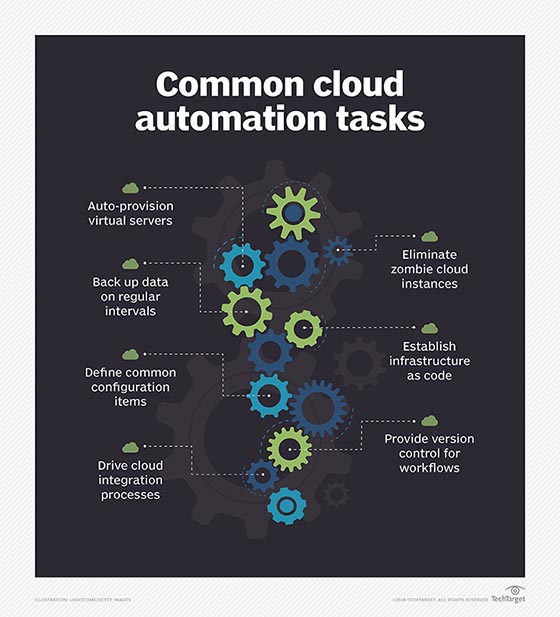

Cloud automation in private, public and hybrid cloud environments embraces processes and tools that reduce or eliminate the manual efforts used to deploy and manage cloud computing workloads and services. IT teams use orchestration and automation tools that run on top of a virtualized environment.

Cloud automation can improve several aspects of business operations, including quality control, efficiency, and performance and cost management. It eliminates functions subject to human error and frees up engineers and developers to focus on innovation instead of repetitive, time-consuming tasks during the deployment and operation of business workloads. Those tasks include cloud deployment procedures; sizing, provisioning and configuring resources, such as VMs; establishing VM clusters and load balancing; creating storage logical unit numbers; invoking virtual networks; and monitoring and managing availability and performance.

Cloud automation provides relief in several key areas of workload deployment and operations:

- Implementation is simpler compared to on-premises deployment and requires less IT intervention.

- Autoscaling the use of compute, memory or networking resources to match demand provides elasticity in resource usage and supports PAYG practices.

- Infrastructure configurations defined through templates and code and implemented automatically increase integration opportunities with associated cloud services.

- Continuous software development relies on automation functions ranging from code scans and version control to testing and deployment.

- Assets can be tagged automatically based on specific criteria, context and conditions of operation.

- Automated security controls in cloud environments enable or restrict access to applications or data and scan for vulnerabilities and unusual performance levels.

- Cloud tools and functions can automatically log all activity involving services and workloads, and monitoring filters can detect anomalies or unexpected events.

- Continuous automatic backup secures data in the event of an unexpected shutdown or cyberattack.

- Smoother, automatic, less error-prone processes contribute to improved IT and corporate governance practices.

Operating in the cloud is subject to several inherent challenges that can affect cloud automation, including the following:

- Public cloud services are only as dependable as the internet connection.

- Access to back-end data is limited and can make maintenance problematic.

- Cloud automation security options can be limited without the ability to customize.

- Vendor lock-in can prove risky when cloud automation depends on one platform.

In recent years, AI and machine learning (ML) techniques have significantly advanced cloud automation by enabling more complex tasks, improving monitoring and maintenance, helping businesses personalize their customers' experience and supporting real-time intelligent decision-making, among other benefits. A significant portion of large enterprises are using their CSP's advanced AI technologies and pretrained ML models for proof-of-concept applications, decision-making analytics and data-driven task automation.

Benefits and challenges of public cloud computing

Enterprises must weigh the advantages and drawbacks of public cloud adoption to determine whether it's the right fit.

Benefits

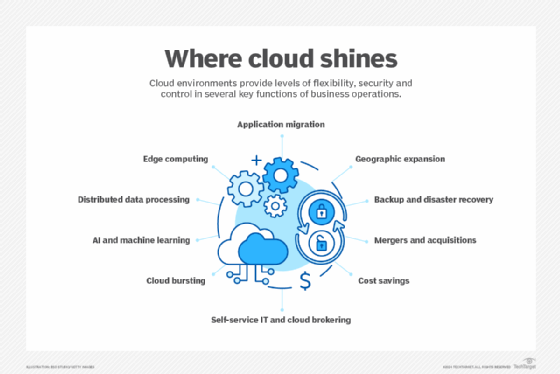

The cloud has many advantages over on-premises IT, including fast technology and application updates, scalability and flexibility, and AI and data analytics democratization.

Access to new technologies. Businesses using large cloud providers get early and instant access to the IT industry's latest technologies, ranging from automatic application updates to complex analytics, AI and ML. Many cloud customers lack the resources -- typically money or in-house expertise -- to develop such capabilities on their own.

Virtually unlimited scalability. Cloud capacity and resources rapidly expand to meet business demands and traffic spikes. Public cloud users also achieve greater redundancy and high availability due to the CSP's various, logically separated cloud locations. In addition to redundancy and availability, businesses achieve faster connectivity between cloud services and end users through their CSP's network interfaces.

Flexibility. The flexible and scalable nature of public cloud resources enables businesses to store high volumes of data and easily access them for computing or retrieval. Many enterprises rely on the cloud for disaster recovery to back up data and applications in case of an emergency or outage. It's tempting to store all data indefinitely, but users should set up a data retention policy that regularly deletes old data from storage to avoid long-term storage costs, maintain privacy and meet appropriate regulatory obligations.

Analytics. Businesses should gather useful metrics on the data they store and resources they use to take full advantage of cloud data analytics. Public cloud services can perform analytics on resource and service usage to determine utilization and cost trends and yield better business insights.

Public cloud benefits also include access to the service provider's reliable infrastructure and a reduction in overhead management tasks, enabling IT staff to focus on functions that are more important to the company, such as writing code for vital business applications.

Challenges

Businesses that use the cloud also face a range of challenges, including pervasive network bandwidth and latency issues as well as internet disruptions.

Runaway costs. Tracking IT spending is becoming increasingly difficult due to complex cloud costs and pricing models. A regular bill from a CSP can consist of thousands of line items that don't correlate to business applications, departments or users. The cloud is often cheaper than on-premises options, but enterprises sometimes exceed their budget because of pricey data egress fees.

Scarce cloud expertise. Companies struggle to hire and retain staff with expertise in building and managing modern cloud applications. IT professionals who hope to fill these roles can better prepare for career opportunities by fine-tuning their cloud skills in areas such as architecture, engineering, operations and coding.

Limited transparency and controls. Public cloud users have limited control over their IT stack since the CSP can decide when and how to manage configurations.

Data separation. The benefits of data separation can be diminished due to multi-tenancy and latency issues for remote users and adherence to industry- and country-specific regulations.

Vendor lock-in. All clouds are not created equal. Although each public cloud offers similar resources and services, the controls and delivery of those assets can vary significantly among CSPs, making it difficult for one data set or application to migrate easily between providers. Vendor dependency can raise costs and limit capabilities for businesses.

Cloud management tools and strategies can help businesses address some of these public cloud challenges and optimize their use of cloud resources and costs.

Public cloud trends to watch

Public cloud is trending in expected and unexpected ways. Developments such as IoT, FinOps and the GDPR that have influenced various aspects of business operations over the past several years will continue to play significant roles in public cloud's future. Then there are the disruptors, including generative AI (GenAI), large language models (LLMs) and edge computing, which could further elevate public cloud's position as the most popular deployment model among enterprises. The key determinant will be whether public clouds can meet the burgeoning demands of power-hungry data centers and data-hungry LLMs.

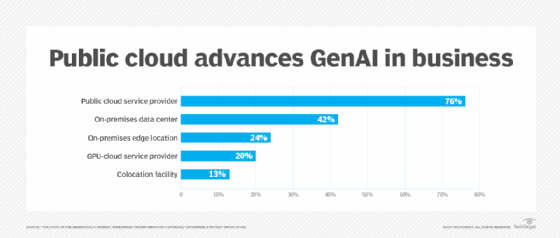

Characterizing 2024 as the year when "adoption and proliferation of cloud-based AI products reached fever pitch," a Forrester Research report on the top 10 cloud trends, released in August, revealed that "AI is entering the mainstream of enterprise cloud consumption." According to a September survey by TechTarget's Enterprise Strategy Group, 76% of organizations worldwide are running their GenAI workloads on public cloud provider platforms, "likely driven by the availability of best-in-class assets and the lower initial cost to experiment."

The public cloud IaaS market reached $140 billion worldwide in 2023, with Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Alibaba and Huawei as the top five CSP beneficiaries, Gartner reported. "Cloud technologies continue to be a major business disruptor, partly due to the focus on hyperscalers looking to support offerings related to sovereignty, ethics, privacy and sustainability," said Gartner analyst Sid Nag in a July press release. "This should continue to drive exponential growth into the future with these offerings being spurred by generative AI investments for 2024 and beyond." While the major CSPs "continue to grow their IaaS offerings in the shadow of GenAI," he added, "we should also see other areas, such as SaaS and PaaS, grow as well. IaaS is the tide that lifts all boats."

Several trends are propelling public cloud computing into the future.

The GenAI effect on infrastructure. To support and capitalize on the integration of AI and GenAI tools into cloud services, CSPs are optimizing their infrastructure and vendors are offering a wider selection of prebuilt and pretrained models, reducing the need for businesses to acquire in-house AI expertise and capabilities. Although cloud vendors stress their LLMs are secure, businesses will need to step up governance and oversight efforts to ensure their AI system components are carefully architected to prevent data leakage. Also, increased integration of AI into cloud management will improve automation, cost optimization, data analysis and IT support.

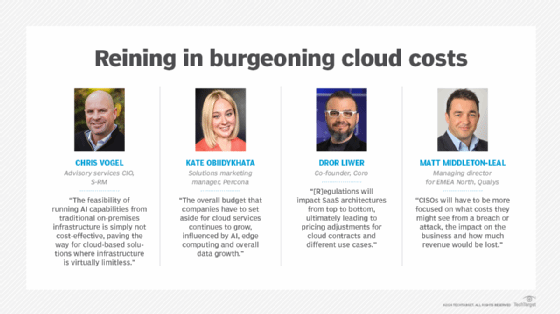

FinOps permeates all aspects of cloud cost management. The scalability and PAYG attributes of cloud services can be quickly offset by unchecked monthly charges, investments in cloud technologies and the need for highly skilled professionals. To manage public cloud costs, FinOps practices can ensure financial accountability among IT, finance and business teams to maximize a cloud's value. FOCUS, the FinOps Open Cost and Usage Specification, will provide CSPs and businesses with consistent cloud cost and usage data sets.

Edge-to-cloud transfer decentralizes centralization. The old approach of transferring IoT data to a centralized location for processing is being replaced by edge computing in distributed cloud environments. As a result, businesses are moving their processing power to the edge of the network and closer to the endpoints for greater efficiency. "The edge-to-cloud play," Forrester reported, "flips the script and positions edge providers as equals to the hyperscalers in the hunt for lucrative enterprise edge business."

WASI-based cloud platforms. Some of the limitations of microservice and serverless approaches will be overcome by using the WebAssembly (Wasm) open standard along with the WebAssembly System Interface (WASI) to run high-performance applications efficiently across cloud platforms and browsers, leading to more modular, portable and scalable development.

New and old sources of energy to feed power-hungry data centers. CSPs and businesses are looking for energy alternatives to power modernized data centers and proliferating GenAI applications. Expect an escalation of conversation around green cloud initiatives, hybrid cloud ecosystems, hyperautomation in those systems and nuclear power.

Governance and compliance pressures mount on cloud management. Stricter enforcement of local, national and regional data privacy laws driven by GenAI's infiltration of business operations are forcing companies to monitor how they use and secure their AI platforms as well as the data feeding AI models. Regulations geared toward data privacy, and AI in particular, are expected to impact SaaS architectures, cloud pricing and use cases.

New and evolving cloud computing skills. Managing operations in the cloud will require new computing skills, including prompt engineering, data center modernization, DevOps, cloud security, risk management, cost management and a better understanding of how a system achieves desired business outcomes.

Differences among public clouds, private clouds and hybrid clouds

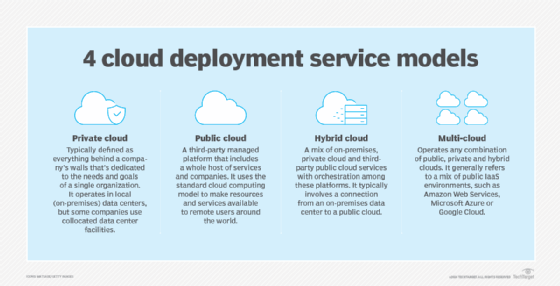

The term public cloud arose to differentiate between the standard cloud computing model and the private cloud model, a proprietary cloud computing architecture dedicated to a single organization. Public and private clouds offer similar services -- compute, storage and networking -- and capabilities such as automation and scalability, but they differ significantly in the way they operate and provide those services.

Public cloud resources run on multi-tenant, shared infrastructure and are available globally to users over the internet. Conversely, private cloud consists of a single-tenant architecture that runs on a company's privately owned on-premises IT infrastructure and is accessible only by the company. It builds on an enterprise's traditional local data center infrastructure by adding layers of virtualization, cloud-type management and services such as resource pooling and on-demand provisioning.

Beyond architectural differences, public and private cloud models differ in price, performance, security and compliance. A private cloud requires a large upfront investment for cloud infrastructure, as opposed to the public cloud's PAYG model. A public cloud can be subject to network bandwidth and connectivity issues, since it largely relies on the public internet. Private cloud can provide more consistent performance and reliability since it's typically a single localized site.

Public and private cloud models can provide extensive security offerings. But private cloud offers more fine-grained control over configurations and physical isolation. It also poses fewer compliance and sovereignty issues, since data doesn't leave the on-premises facility. Organizations with strict compliance needs and cloud aspirations often choose private cloud.

These differences apply to the standard on-premises private cloud. Alternative private cloud models blur the lines between public and private computing. Cloud providers now offer on-premises versions of their public cloud services. AWS Outposts, Azure Stack and Google Anthos, for example, bring physical hardware or bundled software services into an enterprise's physical data center. These distributed deployments act as isolated private clouds, but they're tied to the CSP's cloud and form a type of hybrid cloud implementation.

Hybrid and multi-cloud services

A third model, hybrid cloud, is a combination of public and private cloud services maintained by internal and external providers, with careful orchestration between them. Hybrid cloud enables businesses to tap into the benefits of public cloud for certain workloads but also maintain their own private cloud for sensitive, critical or highly regulated data and applications. Hybrid cloud benefits include flexible deployment options, greater cost control and the ability to move between environments.

A related option is a multi-cloud architecture, in which an enterprise uses more than one cloud. Most often, it refers to the use of multiple public clouds like AWS, Azure and Google. Depending on its needs, a company might use both hybrid and multi-cloud models. But multi-cloud environments are rarely seamless and require careful attention to the unique capabilities and limitations of each cloud provider.

Local computing, public cloud, hybrid cloud and even multi-cloud implementations aren't mutually exclusive. Each infrastructure offers tools that enable a company to host and operate various workloads. It's possible to adopt any mix of infrastructure to meet workload needs and business goals. Yet some alternatives, such as hybrid and multi-cloud options, can be extremely complex and demand high levels of engineering and management expertise.

Public cloud providers and adoption

Estimates of public cloud usage vary widely across different countries, but most market research and analyst firms expect continued growth in worldwide adoption and cloud revenues. Data from Synergy Research Group showed that cloud operator and vendor revenues for the first half of 2024 reached $427 billion, an increase of 23% compared to the first half of 2023.

The big three CSPs, AWS, Microsoft and Google, have captured the lion's share of the public cloud market, with several other providers focusing on specialized smaller segments. CSPs deliver their services over the internet or through dedicated connections, and they use a fundamental pay-per-use approach. Each provider offers a range of products oriented toward different workloads and enterprise needs:

- AWS. The leading public cloud vendor with the largest customer base, AWS was one of the earliest companies to provide scalable PAYG cloud services. The company initially launched its cloud services platform to support the resource demands of Amazon's retail business. It has since expanded to provide cloud services to users worldwide. AWS offers more than 200 products for compute, databases and infrastructure management, as well as more advanced application development services for AI, ML and IoT.

- Microsoft Azure. The second largest public cloud provider, Azure offers the same types of computing services as its main competitor, AWS. Azure has a well-established PaaS portfolio grouped in the Azure App Service.

- Google Cloud Platform. GCP has a less extensive list of cloud offerings than AWS and Azure, but it has a growing user base and continues to add services mainly focused on data analytics, AI and ML tasks.

Similar to the emergence of AWS from Amazon, Alibaba Cloud was created to support the Alibaba e-commerce parent company, which operates in international regions but is primarily focused on domestic Chinese and other Asian markets, offering infrastructure, storage, networking and other application services.

Salesforce, known primarily for its CRM products, offers various types of cloud platforms geared to specific business functions, including sales management, marketing automation, customer service, commercial transactions and data analytics.

IBM Cloud provides IaaS and PaaS offerings. Big Blue acquired open source software company Red Hat in 2019 to provide users with more flexible service options and extended hybrid cloud capabilities.

Oracle, primarily known for its database offerings, provides public cloud services with Oracle Cloud Infrastructure. The IaaS offering targets businesses requiring custom, high-performance computing and specialization.

Tencent Cloud is an IaaS cloud provider based in Shenzhen, China, offering individual products and services within its cloud, ranging from streaming media to compute and container services.

Categories of available public cloud services

Each cloud provider offers tools and services across many categories, including compute, storage, container management and serverless computing. Although these offerings generally work the same, they're not identical, so businesses must be mindful of any unique requirements or dependencies.

Compute. Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) is an IaaS service that provides compute capacity for AWS deployments on virtual servers, known as EC2 instances. There are various EC2 instance types and sizes designed for different user needs, including memory, storage and compute-optimized instances. Microsoft's primary compute service is Azure Virtual Machines, which similarly varies for compute, memory and general use. GCP's IaaS compute service is called Google Compute Engine.

Storage. Each provider offers various storage types, such as block, object and file. The Amazon S3 object storage service is available in storage tiers that vary by access frequency. Other storage offerings on AWS include Amazon Elastic Block Store and Elastic File System. Microsoft storage offerings include Azure Blob Storage for object storage, Files for file storage and Managed Disks for block storage. Google offers Cloud Storage buckets for object storage; Filestore for file storage; and Zonal Persistent Disk, Regional Persistent Disk and Local SSD for block storage.

Containers. AWS has four container management offerings: Amazon Elastic Container Service, Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service, Amazon Elastic Container Registry and AWS Fargate. AWS containers can also be manually deployed on EC2 instances. Microsoft's container management services include Azure Kubernetes Service, Container Registry and Container Instances. GCP containers can run on Google Kubernetes Engine, Cloud Run and Compute Engine.

Serverless. The primary serverless products from the big three providers are AWS Lambda, Azure Functions and Google Cloud Functions.

Database. Public cloud providers routinely provide major back-end enterprise applications as managed services, such as database applications. Examples include Amazon Relational Database Service and DynamoDB, Google Cloud SQL and BigQuery, and Azure SQL and Cosmos DB. Employing a cloud provider's database service alleviates the need for a business to deploy and maintain its own database application in the public cloud.

AI and ML. The rapid growth of AI and ML in business has spawned a range of cloud-based services to support these technologies. Examples include Amazon SageMaker and Amazon Polly, Azure Machine Learning Studio and Google Vertex AI Studio. These services help businesses ingest and process data and provide the ability to build and deploy AI/ML platforms for businesses.

Public cloud providers also offer various tools and services for networking, monitoring, analytics, IoT, big data support and human-machine interaction, such as text-to-speech technology.

Public cloud pricing

Public cloud pricing is typically billed on a pay-per-use or PAYG structure, in which cloud users pay only for the resources they consume. This option can help reduce IT expenses, since a company no longer needs to purchase and maintain physical infrastructure for the parts of its business deployed to a public cloud IaaS. Also, a company can account for public cloud expenditures as operational or variable costs rather than capital or fixed costs. Operational spending decisions typically require less-intensive reviews or budget planning.

These cost benefits can be easily erased because of the difficulty in accurately tracking cloud service usage in the self-service model. Businesses can suffer sticker shock from unexpected charges. Common public cloud cost pitfalls include the following:

- Overprovisioning resources.

- Inability to correlate cloud spend to specific business workloads or departments.

- Cloud sprawl, or failure to decommission idle workloads.

- Unnecessary data egress fees.

In addition, public cloud providers have complex pricing models with rates that vary by region and service. These models can contain hidden costs that drive up the cloud usage bill.

All usage in the cloud is metered. CSPs consider several cost factors when determining how much to charge businesses, including costs for application migration, networking, computing, data transfers, storage, resource consumption, database services, software licensing, security services and the products to manage and maintain the environment.

Ironically, the principal challenge is self-service. Since every cloud user is free to establish public cloud accounts, there's a natural lack of oversight and centralization to organize and track costs. One department, for example, might not know what another department is doing in the cloud, leading to redundancy and waste. Recent initiatives, such as cloud FinOps, are emerging to help enterprises oversee and centralize public cloud use across the business and maximize cloud utilization and benefits.

Cost optimization strategies

To rein in cloud costs, enterprises should consistently monitor their cloud bill and reevaluate deployment models to ensure the most cost-efficient approach.

There are visibility tools and strategies that estimate costs and identify spending patterns. Cloud providers offer pricing calculators and cost monitoring tools, such as AWS Cost Explorer, Azure Pricing Calculator and Google Cloud Cost Management.

CSPs offer various discount programs, such as cheaper alternatives to on-demand resources. AWS and Azure, for example, offer reserved instances at a lower price in exchange for a company's commitment to use a certain amount of capacity within a specified time period.

Autoscaling features can help control costs by adjusting application scale to meet demand and avoid paying for unnecessary capacity. With proper visibility into the cloud environment, IT teams can identify and shut down idle workloads to avoid paying for unused resources and prevent cloud sprawl.

Public cloud security

The ongoing security concern for many businesses is the multi-tenancy inherent in the public cloud model. Since companies host sensitive data and critical workloads in the cloud, protecting their assets in this shared space is a top priority. CSPs offer various security services and technologies, but security in the cloud requires diligence from both the provider and the enterprise.

Shared responsibility

Public cloud security responsibilities are split between the provider and cloud user as outlined in a shared responsibility model. This framework designates the specific aspects of security and accountability shared by the CSP and the enterprise. The specific tasks in a security agreement differ depending on the provider and public cloud model.

Typically, a cloud provider is expected to secure the infrastructure that supports the cloud environment, including the hardware, software, network, storage and on-premises facilities used to run cloud services. The enterprise is responsible for establishing and maintaining security for data and workloads. It's like renting a home, where the landlord maintains the property, while the tenant locks the doors and closes the windows.

Public cloud security challenges

Securing cloud-hosted applications requires protection against external threats, such as malicious attacks and data breaches, and internal security risks, like misconfigured resources and weak access management policies. It's also important to map data flows, ensure traceability, use encryption and understand how data is protected in transit and at rest.

Security tools and practices

CSP security services and technologies include encryption, identity and access management (IAM), and identity governance and administration (IGA) tools. Security monitoring tools scan and observe the services and resources in the cloud environment and generate alerts when a potential security issue arises. Access control is also critical to public cloud security. Strong IAM and IGA policies should allot only the necessary level of permissions, such as zero-trust policies. It's important to consistently update IAM policies and remove access for users that no longer require certain permissions. Multifactor authentication bolsters user verification.

A well-trained IT staff also ensures a safe cloud environment. Many vulnerabilities are the result of resource misconfigurations due to human error. IT staff should monitor and maintain local and cloud configurations and be up to date on security policies.

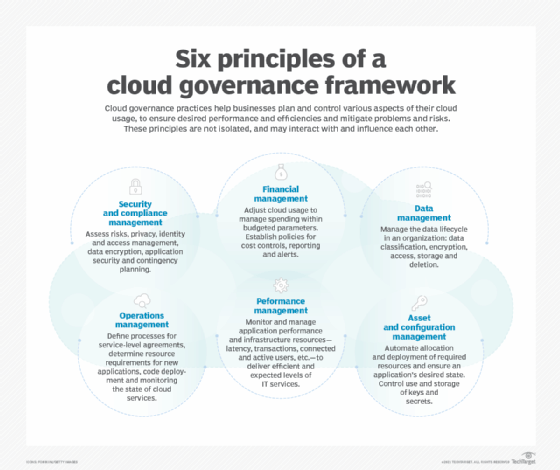

Governance and compliance in public cloud

Businesses operating in the cloud face significant governance and compliance challenges, heightened by the growing use of AI and increasingly strict cloud data privacy regulations. According to a Forrester Research August 2024 trends report, an "exponential increase in third-party risk [is] due to the embrace of black box AI models and mounting pressure to align with regulatory and compliance requirements for localization."

Even more so in the cloud than on-premises, a well-devised governance framework and clear guidelines are essential. On-premises, governance practices are in a somewhat controlled environment. In the cloud and among distributed clouds, data and workloads are constantly in motion or stored in locations not necessarily controlled by the enterprise.

Governance sets policies for cloud usage, outlines enforcement of those policies, and should align with and support business needs. Due to the nature of cloud environments, governance practices can change frequently and directly influence a company's overall cloud strategy.

A governance framework should permeate the entire business and typically includes guidance on data management and protection, security and regulatory compliance, operations and performance management, access to cloud resources and cost optimization. It can also involve the assignment of roles and responsibilities, procedures for backup and disaster recovery, and policies surrounding provisioning, performance monitoring and deprovisioning.

Amid proliferating local, national and regional data privacy regulations as well as data sovereignty issues, a company's compliance policies should set standards for meeting regulatory requirements involving data storage, processing and protection in the cloud.

Cloud providers are increasingly tailoring resources and services to industry sectors that require adherence to specific compliance requirements, such as HIPAA and the GDPR. Businesses without specific industry obligations can also implement cloud usage, data protection, security and business continuance policies that meet general regulatory requirements.

Businesses should be aware that compliance measures for encryption, access control and monitoring that are effective for an on-premises infrastructure might not necessarily translate to the CSP's infrastructure and potentially lead to gaps in security and compliance. Enterprises also must determine whether the CSP's practices can properly support the company's security and compliance needs.

Public cloud providers offer compliance frameworks that can detect anomalies in real time. Many companies that adopt cloud data storage running on the CSP's infrastructure keep their sensitive data on-premises to meet data compliance requirements. Businesses that use public cloud AI services should perform regular audits for compliance.

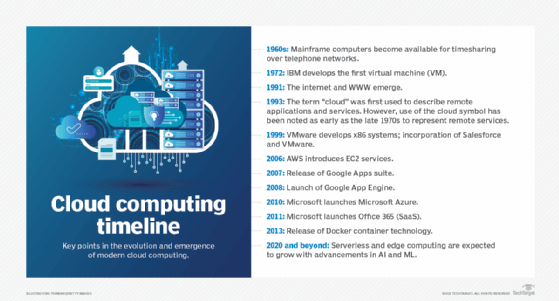

Public cloud's milestones in history

While the concept of cloud computing has been around since the 1960s, it didn't reach public popularity for enterprises until the 1990s. Salesforce, now a top SaaS provider, entered the market in 1999 by delivering applications through a website. Browser-based applications that could be accessed by numerous users, such as G Suite, soon followed.

In 2006, Amazon launched its EC2 IaaS platform for public use. Under its AWS cloud division, enterprises could "rent" virtual computers but use their own systems and applications. Soon after, Google released its PaaS service, App Engine, for application development, and Microsoft released its Azure PaaS offering. Over time, all three CSPs built IaaS, PaaS and SaaS offerings. Legacy hardware vendors, such as IBM and Oracle, also entered the market.

But not all vendors that entered the market succeeded. Verizon, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Dell, VMware and others ultimately shut down their public clouds, and some of them have refocused on hybrid cloud and cloud management.

Public cloud adoption continues to rise as providers expand their portfolios of services and support. Technology developments, such as AI, ML, IoT and edge computing, have infiltrated public cloud service portfolios. More diverse cloud app development approaches have also emerged as businesses embrace microservices, containers and serverless architectures.

The next wave of public cloud computing is expected to involve more automation and specialization. CSPs will offer more granular and interconnected services to meet broader business needs. Emerging technologies and IT developments, such as quantum computing, will shape the future of the public cloud.

Editor's note: This article was updated from 2023 to reflect the latest issues and developments in public cloud computing.

Stephen J. Bigelow, senior technology editor at TechTarget, has more than 20 years of technical writing experience in the PC and technology industry.

Kathleen Casey is site editor for TechTarget Cloud Computing. She plans and oversees the site and covers various cloud subjects, including infrastructure management, development and security.

Ron Karjian is an industry editor and writer at TechTarget covering business analytics, artificial intelligence, data management, security and enterprise applications.