What is a cyberattack? 16 common types and how to prevent them

To stop cybercrime, companies must understand how they're being attacked. Here are the most damaging types of cyberattacks, how to prevent them and their effect on daily business.

A cyberattack is a malicious attempt by individuals, criminal groups or government-sponsored entities to gain unauthorized access to computer systems or networks with the intent to cause damage. The motivations behind cyberattacks vary, including financial gain, disruption, revenge and corporate espionage. With these different motives and the increasing sophistication of attackers, many security teams are struggling to keep their IT systems secure.

A variety of cyberattacks are launched against organizations every day. According to threat intelligence provider Check Point Research, there was a weekly average of 1,925 attacks per organization worldwide in the first quarter of 2025.

According to data and business intelligence platform firm Statista, the global cost of cybercrime is predicted to hit $10.29 trillion in 2025, while the average cost of a data breach will rise to almost $5 million per IBM's "Cost of a Data Breach Report 2024." The costs of cyberattacks are both tangible and intangible, including not only direct loss of assets, revenue and productivity, but also reputational damage that can lead to loss of customer trust and the confidence of business partners.

Cybercrime is built around the efficient exploitation of vulnerabilities, and security teams are always at a disadvantage because they must defend all possible entry points; an attacker, on the other hand, only needs to find and exploit one weakness or vulnerability. This asymmetry highly favors attackers. The result is that even large enterprises struggle to prevent cybercriminals from monetizing access to their networks, which typically must maintain open access and connectivity while security professionals try to protect enterprise resources.

Cyberattacks aren't confined to just large organizations. Cybercriminals can use any internet-connected device as a weapon, a target or both, and SMBs tend to deploy less sophisticated cybersecurity measures -- opening them up to potential security incidents.

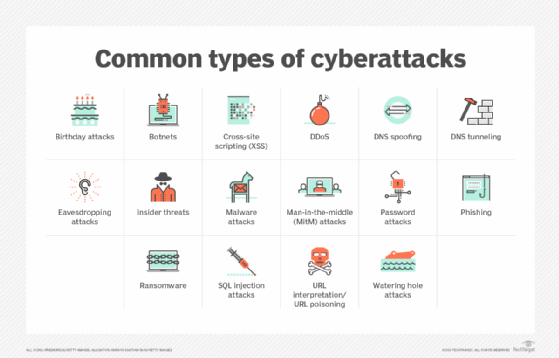

Security managers and their teams need to be prepared for all the different attacks they might face. To help with that, here are 16 of the most damaging types of cyberattacks and how they work.

16 most common types of cyberattacks

1. Malware attack

Malware, short for malicious software, is an umbrella term used to refer to a hostile or intrusive program or file that's designed to exploit devices at the expense of the user and to the benefit of the attacker. There are various forms of malware that all use evasion and obfuscation techniques designed to not only fool users but also elude security controls so they can install themselves on a system or device surreptitiously without permission.

Currently, the most feared form is ransomware, a program that attackers use to encrypt a victim's files and then demand a ransom payment in order to receive the decryption key. Because of ransomware's prominence, it's covered in more detail below in its own section. The following are some other common types of malware:

- Rootkit. Unlike other malware, a rootkit is a collection of software tools used to open a backdoor on a victim's device. That enables the attacker to install additional malware, such as ransomware and keyloggers, or to gain remote access to and control of other devices on the network. To avoid detection, rootkits often disable security software. Once the rootkit has control over a device, it can be used to send spam email, join a botnet or collect sensitive data and send it back to the attacker.

- Trojan. A Trojan horse is a program downloaded and installed on a computer that appears harmless but is, in fact, malicious. Typically, this malware is hidden in an innocent-looking email attachment or free download. When a user clicks on the attachment or downloads the program, the malware is transferred to their computing device. Once inside, the malicious code executes whatever task the attacker designed it to perform. Often, this is to launch an immediate attack, but it can also create a backdoor for the hacker to use in future attacks.

- Spyware. Once installed, spyware monitors the victim's internet activity, tracks login credentials and spies on sensitive information -- all without the user's consent or knowledge. For example, cybercriminals use spyware to obtain credit card and bank account numbers and to get passwords. Government agencies in many countries also use spyware -- most prominently, a program named Pegasus -- to spy on activists, politicians, diplomats, bloggers, research laboratories and allies.

2. Ransomware attack

Ransomware is usually installed when a user visits a malicious website or opens a doctored email attachment. Traditionally, it exploits vulnerabilities on an infected device to encrypt important files, such as Word documents, Excel spreadsheets, PDFs, databases and system files, making them unusable. The attacker then demands a ransom in exchange for the decryption key needed to restore the locked files. The attack might target a mission-critical server or try to install the ransomware on other devices connected to the network before activating the encryption process so they're all hit simultaneously.

To increase the pressure on victims, attackers also often threaten to sell or leak data exfiltrated during an attack if the ransom isn't paid. In fact, in a shift in ransomware tactics, some attackers are now relying solely on data theft and potential public disclosures to extort payments without even bothering to encrypt the data.

Ransomware is such a serious problem that the U.S. government created a website called StopRansomware in 2021. The website provides resources to help organizations prevent attacks and a checklist on how to respond to one.

3. Password attack

Despite their many known weaknesses, passwords are still the most common authentication method used for computer-based services, so obtaining a target's password is an easy way to bypass security controls and gain access to critical data and systems. Attackers use various methods to illicitly acquire passwords, including these:

- Brute-force attack. An attacker can try well-known passwords, such as password123, or ones based on information gathered from a target's social media posts -- like the name of a pet -- to guess user login credentials through trial and error. In other cases, they deploy automated password cracking tools to try every possible combination of characters.

- Dictionary attack. Similar to a brute-force attack, a dictionary attack uses a preselected library of commonly used words and phrases, depending on the location or nationality of the victim.

- Social engineering. It's easy for an attacker to craft a personalized email or text message that looks genuine by collecting information about someone from their social media posts and other sources. As a form of social engineering, these messages can be used to obtain login credentials under false pretenses by manipulating or tricking the person into disclosing the information, particularly if they're sent from a fake account impersonating someone the victim knows.

- Keylogging. A keylogger is software that secretly monitors and logs every keystroke by users to capture passwords, PIN codes and other confidential information entered via the keyboard. This information is sent back to the attacker via the internet.

- Password sniffing. A password sniffer is a small program installed on a network that extracts usernames and passwords sent across the network in cleartext. While still used by attackers, it's no longer the threat it used to be because most network traffic is now encrypted.

- Stealing or buying a password database. Hackers can try to breach an organization's network defenses to steal its database of user credentials and then either use the data themselves or sell it to others.

4. DDoS attack

A DDoS attack involves the use of numerous compromised computer systems or mobile devices to target a server, website or other network resource. The goal is to slow it down or crash it completely by sending a flood of messages, connection requests or malformed packets, thereby denying service to legitimate users.

More than 8.9 million DDoS attacks were launched in the first half of 2025, according to a report by performance management and security software vendor Netscout. Political or ideological motives are behind many of the attacks, but they're also used to seek ransom payments. In some cases, attackers threaten an organization with a DDoS attack if it doesn't meet their ransom demand. Attackers are also harnessing the power of AI tools to improve attack techniques and direct their networks of infected machines to perform DDoS attacks accordingly. Worryingly, AI is now being used to enhance all forms of cyberattacks, although it has potential cybersecurity uses, too.

5. Phishing

In phishing, an attacker masquerades as a reputable organization or individual to trick an unsuspecting victim into handing over valuable information, such as passwords, credit card details and intellectual property. Based on social engineering techniques, phishing campaigns are easy to launch and surprisingly effective. Emails are most commonly used to distribute malicious links or attachments, but phishing attacks can also be conducted through text messages (SMS phishing, or smishing) and phone calls (voice phishing, or vishing).

Spear phishing targets specific people or companies, while whaling attacks are a type of spear phishing aimed at senior executives in an organization. Business email compromise (BEC) is a related attack in which an attacker poses as a top executive or other person of authority and asks employees to transfer money, buy gift cards or take other actions. The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center puts phishing and BEC attacks in separate categories. In 2024, it received 21,442 complaints about BEC attacks, with total losses of more than $2.7 billion, and 193,407 phishing complaints that generated more than $70 million in losses.

6. SQL injection attack

Any website that is database-driven -- and that's the majority of websites -- is susceptible to SQL injection attacks. A SQL query is a request for some action to be performed on a database, and a well-constructed malicious request can create, modify or delete the data stored in the database. It can also read and extract data, such as intellectual property, personal information of customers or employees, administrative credentials and private business details.

SQL injection continues to be a widely used attack vector. It was third on the 2024 Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) Top 25 list of the most dangerous software weaknesses, which is maintained by The Mitre Corp. In 2024, according to the website CVEdetails.com, there were 2,646 SQL injection attacks. In a high-profile example of a SQL injection attack, attackers used one of those vulnerabilities to gain access to Progress Software's MoveIt Transfer web application, leading to data breaches at thousands of organizations that use the file transfer software.

7. Cross-site scripting

This is another type of injection attack in which an attacker adds a malicious script to content on a legitimate website. Cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks occur when an untrusted source is able to inject code into a web application, and the malicious code is then included in webpages that are dynamically generated and delivered to a victim's browser. This enables the attacker to execute scripts written in languages such as JavaScript, Java and HTML in the browsers of unsuspecting website users.

Attackers can use XSS to steal session cookies, which lets them pretend to be victimized users. But they can also distribute malware, deface websites, seek user credentials and take other damaging actions through XSS. In many cases, it's combined with social engineering techniques, such as phishing. A constant among common attack vectors, XSS ranked first on the CWE Top 25 list for 2024.

8. Man-in-the-middle attack

In a man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack, the attacker secretly intercepts messages between two parties -- for example, an end user and a web application. The legitimate parties believe they're communicating directly with each other, but in fact, the attacker has inserted themselves in the middle of the electronic conversation and taken control of it. The attacker can read, copy and change messages, including the data they contain, before forwarding them on to the unsuspecting recipient, all in real time.

A successful MitM attack enables attackers to capture or manipulate sensitive personal information, such as login credentials, transaction details, account records and credit card numbers. Such attacks often target the users of online banking applications and e-commerce sites, and many involve the use of phishing emails to lure users into installing malware that enables an attack.

9. URL interpretation/URL poisoning

It's easy for attackers to modify a URL to access information or resources. For example, if an attacker logs in to a user account they've created on a website and can view their account settings at https://www.awebsite.com/acount?user=2748, they can easily change the URL to, say, https://www.awebsite.com/acount?user=1733 to see if they can access the account settings of the corresponding user. If the site's web server doesn't check whether each user has the correct authorization to access the requested resource -- particularly if it includes user-supplied input -- the attacker likely will be able to view the account settings of every other user on the site.

A URL interpretation attack, also sometimes referred to as URL poisoning, is used to gather confidential information, such as usernames and database records, or to access admin pages that are used to manage a website. If an attacker does manage to access privileged resources by manipulating a URL, it's commonly due to an insecure direct object reference vulnerability in which the site doesn't properly apply access control checks to verify user identities.

10. DNS spoofing

The DNS enables users to access websites by mapping domain names and URLs to the IP addresses that computers use to locate sites. Hackers have long exploited the insecure nature of DNS to overwrite stored IP addresses on DNS servers and resolvers with fake entries, directing victims to an attacker-controlled website instead of the legitimate one. These fake sites are designed to look exactly like the sites that users expect to visit. As a result, victims of a DNS spoofing attack aren't suspicious when asked to enter their account login credentials on what they think is a genuine site. That information enables the attackers to log in to user accounts on the sites being spoofed.

11. DNS tunneling

Because DNS is a trusted service, DNS messages typically travel through an organization's firewalls in both directions with little monitoring. However, this means an attacker can embed malicious data, such as command-and-control messages, in DNS queries and responses to bypass -- or tunnel around -- security controls. For example, the hacker group OilRig, which has suspected ties to Iran, is known to use DNS tunneling to maintain a connection between its command-and-control server and the systems it's attacking.

A DNS tunneling attack uses a tunneling malware program deployed on a web server with a registered domain name. Once the attacker has infected a computer behind an organization's firewall, the malware installed there attempts to connect to the server with the tunneling program, which involves a DNS request to locate it. This provides a connection for the attacker to a protected network.

There are also valid uses for DNS tunneling -- for example, antivirus software vendors send malware profile updates in the background using DNS tunneling. As a result, DNS traffic must be monitored to ensure that only trusted traffic is allowed to flow through a network.

12. Botnet attack

A botnet is a group of internet-connected computers and networking devices that are infected with malware and controlled remotely by cybercriminals. Attackers are also compromising vulnerable IoT devices to increase the size and power of botnets. Botnets are often used to send email spam, engage in click fraud campaigns and generate malicious traffic for DDoS attacks.

Discovered in 2025, the Eleven11bot -- involving more than 30,000 compromised security cameras and network video recorders -- is conducting DDoS attacks on telecom providers and gaming platforms. Security researchers from Nokia Deepfield and GreyNoise reported that the botnet is also executing brute-force attacks by exploiting weak passwords on IoT devices. Notably, more than 60% of the observed IP addresses are linked to Iran.

The objective for creating a botnet is to infect as many devices as possible and then use the combined computing power and resources of those devices to automate and magnify malicious activities.

13. Watering hole attack

In what's known as a drive-by attack, an attacker uses a security vulnerability to add malicious code to a legitimate website so that, when users go to the site, the code automatically executes and infects their computer or mobile device. It's one form of a watering hole attack, in which attackers identify and take advantage of insecure sites that are frequently visited by users they wish to target -- for example, employees or customers of a specific organization or even in an entire sector, such as finance, healthcare or the military.

Because it's hard for users to identify a website that has been compromised by a watering hole attack, it's a highly effective way to install malware on their devices. With the prospective victims trusting the site, an attacker might even hide the malware in a file that users intentionally download. The malware in watering hole attacks is often a remote access Trojan that gives the attacker remote control of infected systems.

14. Insider threat

Employees and contractors have legitimate access to an organization's systems, and some have an in-depth understanding of its cybersecurity defenses. This can be used maliciously to gain access to restricted resources, make damaging system configuration changes or install malware. Insiders can also inadvertently cause problems through negligence or a lack of awareness and training on cybersecurity policies and best practices.

It was once widely thought that insider threat incidents outnumbered attacks by outside sources, but that's no longer the case. Verizon's "2024 Data Breach Investigations Report" noted that external actors were responsible for 81% of the breaches that were investigated. However, insiders were involved in 18% of them -- nearly one in five. Some of the most prominent data breaches have been carried out by insiders with access to privileged accounts. For example, Edward Snowden, a National Security Agency contractor with administrative account access, was behind one of the largest leaks of classified information in U.S. history starting in 2013. In 2023, a member of the Massachusetts Air National Guard was arrested and charged with posting top-secret and highly classified military documents online.

15. Eavesdropping attack

Also known as network or packet sniffing, an eavesdropping attack takes advantage of poorly secured communications to capture traffic in real time as information is transmitted over a network by computers and other devices. Hardware, software or a combination of both can be used to passively monitor and log information and "eavesdrop" on unencrypted data from network packets. Network sniffing can be a legitimate activity done by network administrators and IT security teams to resolve network issues or verify traffic. However, attackers can exploit similar measures to steal sensitive data or obtain information that enables them to penetrate further into a network.

To enable an eavesdropping attack, phishing emails can be used to install malware on a network-connected device, or hardware can be plugged into a system by a malicious insider. An attack doesn't require a constant connection to the compromised device; the captured data can be retrieved later, either physically or by remote access. Due to the complexity of modern networks and the sheer number of devices connected to them, an eavesdropping attack can be difficult to detect, particularly because it has no noticeable effect on network transmissions.

16. Birthday attack

This is a type of cryptographic brute-force attack to obtain digital signatures, passwords and encryption keys by targeting the hash values used to represent them. It's based on the birthday paradox, which states that, in a random group of 23 people, the chance that two of them have the same birthday is more than 50%. Similar logic can be applied to hash values to enable birthday attacks.

A key property of a hash function is collision resistance, which makes it exceedingly difficult to generate the same hash value from two different inputs. However, if an attacker generates thousands of random inputs and calculates their hash values, the probability of matching stolen values to discover a user's login credentials increases, particularly if the hash function is weak or passwords are short. Such attacks can also be used to create fake messages or forge digital signatures. As a result, developers need to use strong cryptographic algorithms and techniques that are designed to be resistant to birthday attacks, such as message authentication codes and hash-based message authentication codes.

How to prevent common types of cyberattacks

The more devices that are connected to a network, the greater its value. For example, Metcalfe's law asserts that the value of a network is proportional to the square of its connected users. Especially in large networks, it becomes harder to increase the cost of an attack to the point where attackers give up. Security teams must accept that their networks will be under constant attack. By understanding how different types of cyberattacks work, mitigation controls and strategies can be put in place to minimize the damage they do. Here are the main points to keep in mind:

- Attackers, of course, first need to gain a foothold in a network before they can achieve whatever objectives they have, so they need to find and exploit vulnerabilities or weaknesses in an organization's IT infrastructure. Being diligent about identifying and fixing those issues -- through an effective vulnerability management program, for example -- reduces the potential for attacks.

- Vulnerabilities aren't only technology-based. According to Verizon's "2024 Data Breach Investigations Report," 60% of the examined breaches involved a human element, such as errors and falling prey to social engineering techniques. Errors can be either unintentional actions or a lack of action, from downloading a malware-infected attachment to failing to use a strong password. This makes security awareness training a top priority in the fight against cyberattacks, and because attack techniques are constantly evolving, training must be constantly updated as well. Cyberattack simulations can assess the level of cybersecurity awareness among employees and drive additional training when there are obvious shortcomings.

- While security-conscious users can reduce the success rate of cyberattacks, a defense-in-depth strategy is also essential. It should be tested regularly using vulnerability assessments and penetration tests to check for exploitable security vulnerabilities in OSes and applications.

- End-to-end encryption across a network prevents many attacks from successfully extracting valuable data, even if they manage to breach perimeter defenses or intercept network traffic.

- To deal with zero-day exploits, where cybercriminals discover and exploit a previously unknown vulnerability before a fix becomes available, enterprises need to consider adding content disarm and reconstruction technology to their threat prevention controls. Instead of trying to detect malware functionality that continually evolves, it assumes all content is malicious and uses a known bad vs. known good approach to remove file components that don't comply with the file type's specifications and format.

- Security teams also need to proactively monitor the entire IT environment for signs of suspicious or inappropriate activity to detect cyberattacks as early as possible. Network segmentation creates a more resilient network that can detect, isolate and disrupt an attack. If an attack is detected, there should be a well-rehearsed incident response plan.

The business effects of cyberattacks, with examples

Organizations rely on the data in their IT systems, making them vulnerable to cyberattacks. Consumers and business partners also expect companies to prioritize cybersecurity to keep their private data safe. When the trust between a business and its customers is disrupted by a security breach, some customers might look elsewhere. Lost business as well as reputational damage can have lasting effects on an organization. That all comes on top of the actual costs of recovering from a security incident and upgrading cyber defenses.

Here are some examples of recent cyberattacks and their effect on the businesses involved:

- In 2024, a ransomware attack on CDK Global -- linked to Russian and Eastern European hackers -- forced the automotive technology provider to shut down its systems. During this time, auto dealerships had a limited ability to sell and repair cars, which also affected consumers.

- A ransomware attack on Change Healthcare in 2024 went undiscovered for nine days. This resulted in the healthcare provider having to disconnect more than 100 services and go offline. The company reportedly paid a ransom to the BlackCat/ALPHV ransomware gang, but the breach was so severe that it has taken the organization more than a year to recover. Nebraska's attorney general has since filed a lawsuit against Change Healthcare that claims the company did not implement sufficient security measures.

- In 2023, the U.K.'s Royal Mail fell victim to a ransomware attack perpetrated by Russia-linked ransomware gang LockBit that encrypted crucial files, preventing international shipments for six weeks. Royal Mail refused to pay the initial ransom demand of $80 million or subsequent reduced amounts but said it spent almost $13 million on remediation work and security improvements. In addition, hackers posted stolen data online.

Ultimately, if the connected world is going to survive the never-ending battle against cyberattacks, cybersecurity strategies and budgets need to build in the ability to adapt to changing threats and deploy new security controls when needed while also harnessing the power of AI.

Editor's note: This article was updated in June 2025 to add new data points and examples and to improve the reader experience.

Michael Cobb, CISSP-ISSAP, is a renowned security author with more than 20 years of experience in the IT industry.