Getty Images/iStockphoto

Top 4 Rural Hospital Challenges with Revenue Cycle Management

Physician shortages and higher uninsured rates are among the top issues rural hospitals face with improving revenue cycle management strategies.

Rural hospitals may be the only healthcare option for individuals living in sparsely populated areas, but revenue cycle management challenges have forced many of these facilities to permanently close their doors.

The healthcare industry has seen 81 rural hospital closures between 2010 and August 2017, according to the most recent data from University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

Many other rural hospitals are also vulnerable to closure. About 41 percent of rural facilities operated with negative margins in 2016, a recent Chartis Group and iVantage Health Analytics study of over 2,100 hospitals revealed.

Improving revenue cycle efficiency is key to boosting operating and profit margins for any hospital. But providers who practice in low population density areas face unique challenges when it comes to revenue cycle management optimization.

The unique obstacles that rural hospitals encounter when managing their revenue cycle include severe physician shortages, higher uninsured rates, claims reimbursement limitations, and value-based care implementation issues.

Physician shortages in rural areas drive revenue cycle challenges

The healthcare industry is facing a physician shortage. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recently projected the physician shortage to increase to up to 104,900 providers by 2030.

Their most recent estimate revealed that the shortfall of providers may be more severe than previous projections. The organization reported in 2015 that the physician shortage would reach 90,000 providers by 2025.

While hospitals across the nation are feeling the impact of a shrinking workforce, rural areas have been especially troubled by the lack of providers practicing. Former CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt told attendees at the 2016 CMS Rural Health Summit that even though 20 percent of the population lives in a rural location, only 10 percent of physicians practice in those regions.

The physician shortfall in rural areas represented about 65 percent of the healthcare professional shortage.

Specialist shortages were also a major issue for rural hospitals. Slavitt added that one in eight rural counties did not contain a behavioral health specialist and the counties that did only reported one-third to one-half of the levels compared to their urban peers.

To alleviate challenges stemming from physician shortages, rural hospitals should implement team-based care that includes additional physician assistants and nurse practitioners. Adding the non-physician providers can help rural hospitals improve clinical workflows and reduce costs.

A 2016 case study in the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management showed that hospitalist care teams that employed greater physician assistant to physician ratios significantly decreased healthcare costs compared to hospitalist teams using a traditional staffing model.

A hospital using a higher physician assistant to physician ratio generated patient charges between $7,822 and $7,755, whereas the traditional staffing group produced charges between $8,307 and $10,034.

Clinical workflows also became more efficient with non-physician provider help. Physicians only conducted 36 percent of patient visits under the expanded staffing model versus 96 percent of visits under the traditional model.

With the non-physician providers managing more clinical responsibilities, physicians could focus on more complex cases and hospitals were able to provide additional services.

Rural hospitals can also save on compensation costs because non-physician providers tend to receive substantially less than physicians in annual compensation.

However, rural hospital leaders should be aware of state laws that may prohibit physician assistants and nurse practitioners from engaging in certain services or procedures without physician supervision. In states that restrict non-physician provider activities, hospitals leaders may want to consider advocacy efforts to increase licensure for their staff.

Rural hospitals treat more disadvantaged patient populations

According to Gallup, the national uninsured rate by the end of 2016 was 10.9 percent, marking a record low since the organization started tracking insurance coverage in 2008.

But rural locations experienced higher average uninsured rates, Slavitt stated at the Rural Health Summit. The uninsured rate in rural areas that implemented Medicaid expansion programs under the Affordable Care Act was 11 percent and the rate in rural areas in non-Medicaid expansion states was 14.6 percent.

Treating uninsured individuals increases a hospital’s uncompensated care costs and strains the organization’s revenue cycle. The American Hospital Association (AHA) reported that hospitals faced over $37.5 billion in compensated care costs in 2015.

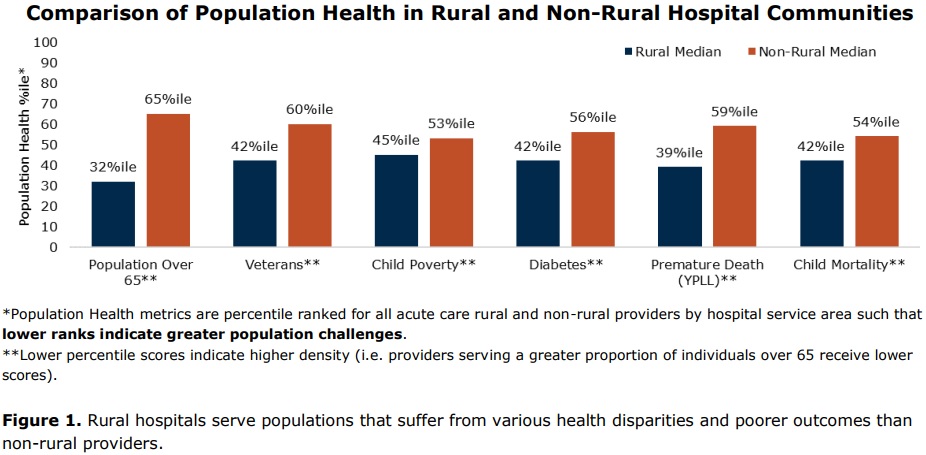

While rural hospitals treated more uninsured individuals, they also saw a greater share of patients with chronic diseases, multiple health issues, and socioeconomic disadvantages.

The facilities overwhelmingly treated more patients over 65 years old, who were veterans, experienced childhood poverty, and suffered from diabetes, stated the Chartis Group and iVantage Health Analytics study. Larger proportions of patients who experienced premature death and increased childhood mortality rates also sought care at rural hospitals.

As a result, rural hospitals tend to experience higher healthcare costs and worse patient outcomes because of their high-risk patient population.

Rural hospitals can alleviate some of the cost burden associated with treating uninsured individuals by connecting with patients, especially those who frequent the emergency department. Providers and administrative staff should ensure that these patients do not qualify for insurance and offer them payment options to reduce uncompensated care costs.

A number of patient financial responsibility options may help patients slowly pay off their medical debt. For example, hospitals can implement payment plans that allow patients to pay off care costs over several months.

Claims reimbursement covers less when mixed with low patient volumes

Rural hospitals may find that claims reimbursement amounts barely cover the costs of services at their facilities.

A recent AHA report found that federal healthcare payments fall significantly below actual hospital costs. In 2015, Medicare reimbursement was $41.6 billion short of actual hospital costs and Medicaid suffered from a $16.2 billion shortfall.

Rural hospitals rely on federal healthcare programs as major revenue streams. The average payer mix at a rural hospital is 61 percent government payers, Michael Topchik, a national leader at Chartis Center for Rural Health recently told the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA).

Unlike urban hospitals that see a steady stream of patients, rural hospitals must stretch Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement to cover expenses.

“Rural hospitals are generally smaller than urban hospitals and have lower patient volumes. This creates challenges as we spread fixed costs over lower volumes, trying to keep costs reasonably in line with PPS [prospective payment system] payment rates,” Tim Wolters, Director of Reimbursement at Citizens Memorial Hospital and Reimbursement Specialist at Lake Regional Health Center, told Congress in 2015.

In light of claims reimbursement challenges, CMS developed four special programs to increase rural hospital payments. The programs are:

• Critical Access Hospital (CAH) designation: cost-based reimbursement for inpatient and outpatient services for geographically isolated hospitals with 25 or fewer inpatient beds and that provide 24-hour emergency services

• Sole Community Hospital program: geographically isolated hospitals receive the greater of the current prospective payment system rate or a base year cost per discharge, may also receive Disproportionate Share Hospital payments to offset uncompensated care costs

• Medicare-Dependent Hospital initiative: hospitals with 100 beds or fewer and a Medicare case load of over 60 percent are paid the greater of the prospective payment system rate or updated base year costs

• Rural Referral Center model: large rural facilities with 275 or more beds receive greater Disproportionate Share Hospital payments

Despite the financial assistance, some rural hospital support from CMS is set to expire in 2017. The AHA recently urged policymakers to back the Rural Hospital Access Act of 2017 that would continue the Medicare-Dependent Hospital Program.

The Senate bill from April 2017 would also adopt MACRA’s definition of a low-volume hospital. The definition states that a hospital is considered low-volume if it is more than 15 road miles (rather 35 miles) from another comparable hospital and has up to 1,600 Medicare discharges (instead of 800 total discharges).

“This improved low-volume adjustment better accounts for the relationship between cost and volume and helps level the playing field for low-volume providers and also sustains and improves access to care in rural areas,” AHA wrote. “If it were to expire, these providers would once again be put at a disadvantage and have severe challenges serving their communities.”

Value-based care implementation remains a major hurdle for rural hospitals

The healthcare industry is shifting from fee-for-service to value-based reimbursement models, but many rural hospitals are being left behind in the process.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently found that small and rural hospitals face unique challenges with implementing value-based reimbursement structures.

“[R]ural practices may face unique challenges when participating in a value-based payment model due, in part, to the geographic dispersion of their patients,” wrote the federal watchdog.

A major obstacle that rural hospitals must overcome with implementing value-based reimbursement models is a lack of financial resources. The GAO reported that initial and ongoing value-based care investments can total thousands, if not millions. Just an interoperable EHR system alone would cost about $20,000.

Rural hospitals also did not have the financial resources to hire additional staff to manage care coordination activities and other capabilities necessary for value-based reimbursement success.

In addition, performance measurement and reporting burdens challenged rural hospitals, the GAO added.

Value-based reimbursement models require hospitals to submit up to a full year’s worth of performance data for claims payment. However, small patient volumes may skew rural hospital performance and negatively impact value-based reimbursement amounts.

Payers also usually require time to analyze performance data, which may take up to two years after submission. The time lag delayed rural hospitals from quickly identifying areas for improvement, therefore jeopardizing financial rewards under the model.

Despite issues with value-based reimbursement implementation, many rural hospitals contain clinicians that qualify for participation in MACRA. CMS designed MACRA to tie a significant portion of Medicare payments to value-based reimbursement and qualifying clinicians must participate or face up to a 4 percent negative payment adjustment.

Eligible clinicians include providers who receive at least $30,000 in Medicare Part B allowable charges and treat a minimum of 100 Medicare beneficiaries. Although, the federal agency proposed to up the threshold to $90,000 in annual Medicare revenue or less than 200 beneficiaries.

CAHs also face special MACRA participation rules based on how clinicians in their facilities bill Medicare for services.

While the participation threshold excludes a substantial portion of rural hospital clinicians, many will still have to report some performance data to avoid a value-based penalty.

CMS plans to help clinicians in rural hospitals be reducing reporting requirements. For example, rural clinicians and those in underserved areas will receive additional points for the Improvement Activities category under MACRA, with medium-weighted activities accounting for 20 points rather than 10 and high-weighted activities accounting for 40 points instead of 20.

The federal agency also allocated $100 million for small and rural clinician support with MACRA implementation and plans to up the funding by $80 million over the next four years.

“Clinicians in small and rural practices are critical to serving the millions of Americans across the nation who rely on Medicare for their healthcare,” stated Kate Goodrich, MD, CMS Chief Medical Officer and Director of the Center for Clinical Standards and Quality.

“Congress, through the bipartisan Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, recognized the importance of small practices and rural practices and provided the funding for this assistance, so clinicians in these practices can navigate the new program, while being able to focus on what matters most -- the needs of their patients,” she continued.