The Global Spread of Mpox: Origins, Symptoms, and Treatment

The recent global spread of mpox has led professionals to investigate and analyze the virus's origins, symptoms, and treatments.

On August 4, 2022, the United States declared mpox a public health emergency. Before 2022, mpox was a relatively contained virus most prevalent in central and west Africa. This new recent spread has made understanding the origins, symptoms, and treatments of this disease essential to minimizing the spread of the disease.

Mpox and Its Origins

The WHO defines monkeypox as a zoonotic virus like smallpox. According to the CDC, “the mpox virus is part of the same family of viruses as variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox. Mpox symptoms are similar to smallpox symptoms but milder, and monkeypox is rarely fatal. Monkeypox is not related to chickenpox.”

While the disease is named mpox, this virus is not derived from monkeys alone. The CDC states that the first discovery of mpox was in a colony of laboratory-contained monkeys in 1958. The spread has been known to originate from many animal species such as squirrels, rats, and other primates.

The virus itself is an orthopoxvirus in the poxviridae family. According to the WHO, “there are two distinct genetic clades of the monkeypox virus: the central African (Congo Basin) clade and the west African clade. The Congo Basin clade has historically caused more severe disease and was thought to be more transmissible. The geographical division between the two clades has so far been in Cameroon, the only country where both virus clades have been found.

Based on information from the Cleveland Clinic, the current mpox outbreak is from the West African clade.

In 1970, the first human mpox viral incidence was reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo, two years after smallpox had been eliminated. That same year a total of 11 countries, including Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan, reported human monkeypox data.

In 2003, the first mpox outbreak in the United States was recorded, marking the first outbreak outside of Africa.

Transmission

Because the transmission of monkeypox is zoonotic, humans can become infected if they come in contact with the bodily fluids of infected animals. However, a common route of infection is eating improperly cooked animal meat of an infected animal.

The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID) states that mpox can enter the body via broken skin or the respiratory tract. “Human-to-human transmission is thought to occur primarily through large respiratory droplets requiring prolonged face-to-face contact,” states the NFID.

Between humans, transmission occurs through contact with respiratory secretions, skin lesions, or recently contaminated objects.

Risk

While African cases are most frequent in children under 15, increased rates are found in men who have sex with men. Despite the correlation, mpox is not an illness isolated to the LGBTQ+ community, meaning anyone can contract this illness with prolonged exposure to an infected individual.

According to the NFID, up to 10% of mpox cases in Africa can lead to death. However, the current outbreak is from a viral clade that has yet to be fatal. Despite the viral infection not being lethal, complications of the illness can be life-threatening for elderly and immunodeficient people.

The cessation of smallpox vaccination campaigns has led to increased risks for those under 40.

Symptoms

Although symptoms of mpox can take up to 21 days to appear, most people’s symptoms appear between 6 and 13 days after infection. Symptoms of this virus can last between 2 and 4 weeks, with pediatric cases being the most severe.

During the invasion period, which can last up to 5 days, the infected person may experience fevers, headaches, swelling of the lymph nodes, muscle aches, and lack of energy.

The more commonly known skin eruption symptoms typically appear between 1 and 3 days from the onset of fever. In 95% of cases, the eruptions affect the face. Furthermore, 75% and 70% of patients have outbreaks on the hands and feet and oral mucus membranes, respectively. Other affected areas include genitalia, conjunctivae, and corneas.

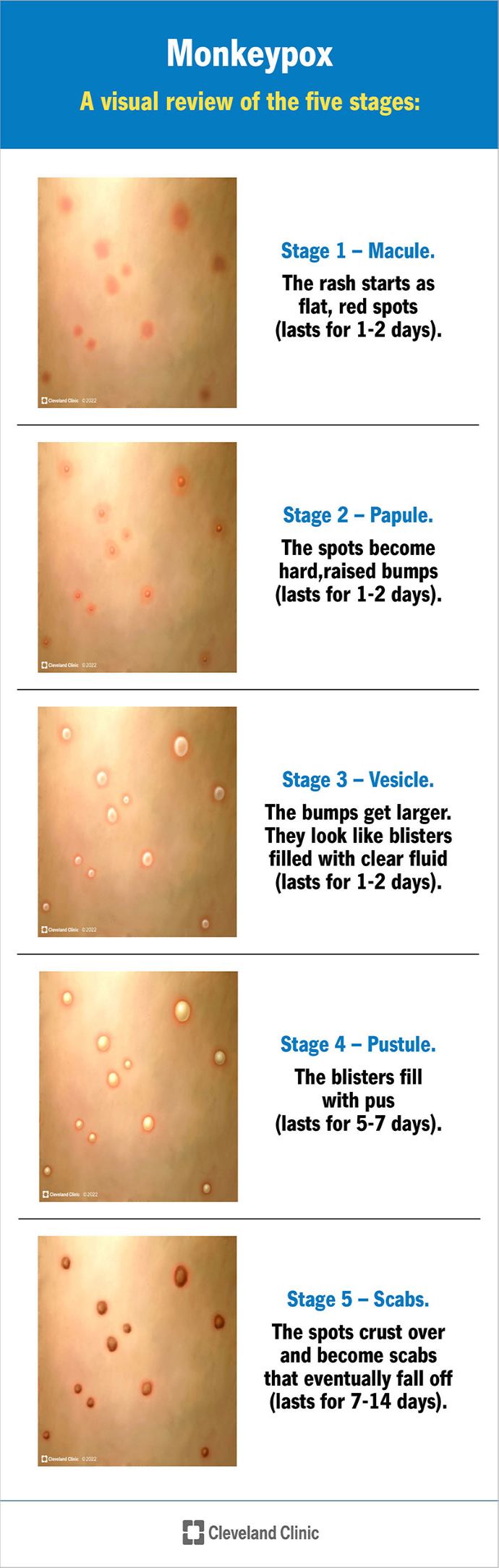

The following Cleveland Clinic image outlines the five stages of mpox skin eruptions — macule, papule, vesicle, pustule, and scabs:

In addition to the primary symptoms, mpox can lead to complications such as other infections, bronchopneumonia, sepsis, encephalitis, and loss of vision.

While all of these symptoms are possible, not all patients will develop all of the symptoms. According to the Cleveland Clinic, many patients in the current outbreak have had an atypical representation of symptoms. This presentation displays minimal lesions. Additionally, swollen lymph nodes and fever are less common.

The atypical representation of symptoms has increased the risk of disease spread as people with these symptoms may not suspect that they have the disease.

Treatment

Similar to other viral infections, there is no cure for mpox. The main therapeutic methods are to treat the symptoms and manage complications. The WHO advises maintaining fluids and eating well to equip the body with the tools to fight off infections.

Infected people should use pain and fever reducers and oatmeal baths to manage the symptoms. Additionally, it is advised that infected people should isolate and cover lesions to prevent the further spread of the disease.

Meanwhile, tecovirimat — an antiviral medication initially developed for smallpox — is being studied for use on patients with mpox.

Diagnosis and Prevention

Like many other viral infections, DNA from the mpox virus is detected via nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), using real-time or conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays.

The best way to minimize mpox infection is to implement prevention strategies, including vaccination if eligible.

Smallpox vaccination provides protection against monkeypox in about 85% of patients. “With the eradication of smallpox in 1980 and subsequent cessation of smallpox vaccination, mpox has emerged as the most important orthopoxvirus for public health,” states the WHO.

In addition to the smallpox vaccine, mpox vaccines are used to protect at-risk populations.

According to the NFID, “JYNNEOSTM is an attenuated live virus vaccine, which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of monkeypox and is being evaluated by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for the protection of those at risk of occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses, such as smallpox and mpox, in a pre-event setting.”

Although there are numerous ways people can avoid infection, some recommended prevention strategies from the Cleveland Clinic include the following:

- avoiding contact with infected animals or people

- avoiding contact with contaminated materials

- proper preparation of animal meat

- frequent hand washing

- using personal protective equipment around infected people

- cleaning and disinfecting surfaces

As the state of disease spread continues to be monitored, the public is urged to be vigilant and take steps to protect themselves. In addition, they should monitor information from the CDC, WHO, and local health departments to assess the state of the illness in their area. At-risk populations should discuss immunization with a licensed healthcare professional.

Editor's Note: This article has been edited to change monkeypox to mpox, following industry guidance.