sdecoret - stock.adobe.com

Preventing Surgical Site Infections, Complexities of Operative Care

With up to 3% of operative patients experiencing surgical site infections (SSI), understanding how to prevent and treat SSIs in complex pre-, peri-, and post-operative care settings can improve patient outcomes.

According to Hopkins Medicine, after surgery, the chances of surgical site infection (SSI) are 1–3%, depending on the type of surgery and operative care. SSIs are most common within 30 days after surgery. Roughly 3% of all SSI cases lead to death. SSIs cause a significant economic burden amounting to $3.3 billion lost annually. Understanding how to effectively prevent surgical site infections and the complex reasonings behind postoperative care can improve patient outcomes and propel treatment advancements.

Types of SSI and Associated Symptoms

There are three different categories of SSI. SSIs can generally cause redness, delayed healing, fever, pain, tenderness, warmth, and swelling. However, depending on the type of SSI, the location of the infection and wound appearance can vary.

First, superficial incisional SSI is contained to the skin in the incision area. A superficial SSI is typically accompanied by discharge from the wound site, which can be sampled and grown in culture to determine the cause and appropriate treatment. According to a StatPearls textbook, roughly 50% of all SSIs are superficial incisional.

Deep incisional SSI is also relatively contained, occurring right beneath the incision area but impacting the muscle, surrounding tissues, and skin. A deep incisional SSI may have discharge; however, this type of SSI also is associated with internal pus.

Finally, organ or space SSI affects the organs or areas between the organs alongside the muscle, surrounding tissues, and skin. According to Hopkins Medicine, this type of SSI may cause an abscess, “an enclosed area of pus and disintegrating tissue surrounded by inflammation.”

Causes of SSI and Risk Factors

SSIs are caused by bacterial infection, most commonly Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Pseudomonas.

Biofilms

A review published in Antibiotics notes that biofilm-forming bacteria cause approximately 80% of SSIs. Researchers in the article commented, “biofilm-associated SSIs are extremely difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics due to several tolerance mechanisms provided by the multidrug-resistant bacteria, usually arranged as polymicrobial communities.”

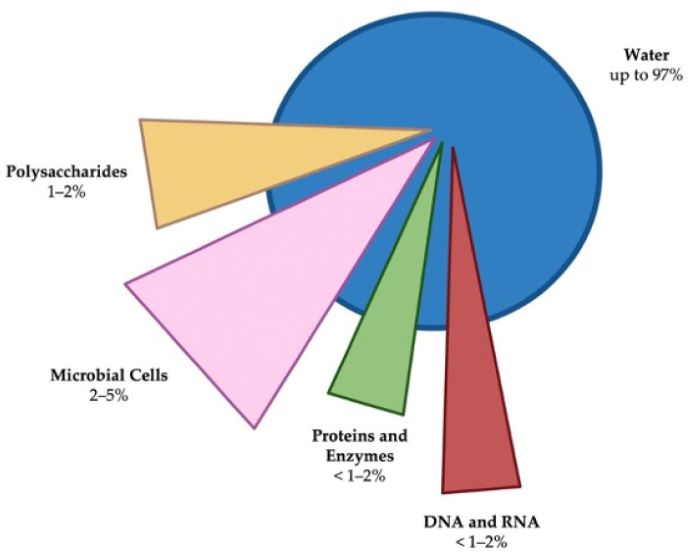

Antibiotics defines biofilms as “complex three-dimensional communities of microorganisms usually found attached to inert or living surfaces and encased within a self-produced protective matrix of extracellular polymeric substances.” A biofilm comprises water, microbial cells, and EPS, which includes polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, extracellular enzymes, metal ions, and nucleic acids.

The biofilm composition allows adherence to surfaces, captures nutrients, and is structurally sound, which prevents antimicrobials and neutrophils from getting rid of it.

Since biofilm-forming bacteria cause most SSIs and are challenging to treat, researchers must find effective methods to prevent these infections.

Risk Factors

Multiple risk factors are associated with post-surgical infection, and StatPearls classifies these into patient and procedural factors.

The risk of SSI depends on multiple factors, including the type of surgery. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, surgical wounds are classified as clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, and dirty. Clean wounds lack inflammation and do not involve operating on an internal organ. Clean-contaminated wounds also do not show signs of infection but involve internal organ operations. Contaminated wounds are when an operation on an internal organ causes the spilling of contents onto the wound. Dirty wounds are wounds with a known infection at the time of surgery.

Procedural risk factors may also include “the formation of a hematoma, the use of foreign material such as drains, leaving dead space, prior infection, duration of surgical scrub, preoperative shaving, poor skin preparation, long surgery, poor surgical technique, hypothermia, contamination from the operating room, and prolonged perioperative stay in hospital.”

Patient risk factors include age, malnutrition, hypovolemia, obesity, steroid use, immunosuppressant use, smoking, and concurrent infections.

Preventing SSI

Although there are many different methods for preventing SSI, each hospital and facility may have rules and protocols that vary depending on the type of surgery, patient risk factors, and more.

According to an article published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, SSI prevention bundles can include antibiotic prophylaxis, skin disinfection, induction and perioperative core temperature control, glove change before closure, intracavity lavage, systemic use of double ring wound protection devices, and predefined closure strategy.

In 2017, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HIPAC) proposed multiple steps to prevent wound infections. The first measures included preparing patients for infection prevention measures and ensuring that patients undergoing surgery have no signs of ongoing infection. If possible, patients with persistent infections should be treated before surgery.

Additional guidelines include skin disinfection and hair removal before surgery. Many sources advise clipping instead of shaving as microscopic cuts from shaving can increase infection risk. In addition, optimal sterility in the operating room is recommended. Finally, many locations recommend peri- and post-operative prophylactic antibiotics and appropriate wound dressings.

Wound Dressings

Wound dressings are the most common way to take care of post-surgical wounds. There are multiple different kinds of wound dressings.

Basic wound dressings include absorbent dressings, surgical absorbents, low-adherence dressings, or wound contact materials. Absorbent dressings are on the wound and may be accompanied by surgical absorbents if the wound releases much fluid. Additionally, low-adherence or wound contact materials are placed directly in contact with the wound. They can be medicated or non-medicated.

Beyond basic wound dressings, there are advanced dressings. Vapor-permeable films, such as OpSite and Tegaderm, are options for dressing wounds to allow water vapor and oxygens through. These wound dressings continue to protect against contamination by liquid water or microorganisms. Other advanced wound dressings include hydrocolloid, fibrous hydrocolloid, and polyurethane matrix hydrocolloid dressings. In addition, antimicrobial dressings such as poly-hexamethylene biguanide dressings are an option.

Looking Ahead

While variations of SSI prevention exist, most facilities use similar techniques. These standard techniques work for most patients, but there is significant room for advancement. One example is advancing wound dressings to be more effective at detecting and preventing SSI.

Smart Bandage

Early in 2021, researchers at the University of Rhode Island developed the first smart bandage to detect and prevent infection. By embedding nanosensors into the bandage fibers, the researchers could advance the use of the bandages.

Daniel Roxbury, URI assistant professor and co-developer of the technology, told URI News that the bandage would be able to detect concentrations of hydrogen peroxide.

The “smart bandage” can be wirelessly monitored by a patient or healthcare professional. The technology is intended for diagnostic purposes, to detect when there is an infection. Roxbury and his codeveloper, Mohammad Moein Safaee, hope that early detection benefits providers and allows them to minimize antibiotic use and prevent drastic measures.

In the interview with URI News, Roxbury notes that this could be particularly beneficial for those with diabetes; however, the implications are endless. While this technology is not yet being used to treat post-surgical infections, future iterations may allow for that route.