Getty Images

Addressing Racial Inequities in US Cancer Clinical Trials

New research shows that African American and Latin American populations lacked representation in US cancer clinical trials, underscoring an access to care issue.

In a recent Phesi analysis of 589,295 patients participating in 6,372 United States cancer clinical trials over the last 15 years, researchers found that 42% of the African American population and 48% of the Latin American population in these trials lacked representation.

These results highlight severe diversity issues in the US clinical development design and recruitment process. “In extreme cases, unintended side effects may occur for those left out of clinical trials,” Gen Li, PhD, MBA, CEO and founder of Phesi, told PharmaNewsIntelligence.

Li explains that a lack of inequitable access to healthcare in the US fuels a lack of patient diversity, affecting Black and Latino communities the most. Although socioeconomic inequality has existed since the founding of America, the accumulation of the associated impacts weighs heavy on the healthcare system today.

Given the high level of genetics and molecular biology researched today, scientists are acutely aware that not all medications work the same for everyone, meaning drug developers must be sophisticated in the clinical design of the drug itself to maximize effectiveness in the intended populations.

In April 2022, the FDA issued a Draft Guidance for Industry aimed to improve the enrollment and participation of underrepresented racial and ethnic populations in clinical trials, including cancer clinical trials.

“It is clear why the FDA has issued the recent guidance on clinical trial diversity, as one-third of the population is not being represented in clinical trials, creating a problem in ensuring that treatments are beneficial for all,” explained Li.

“When a company is developing a new medicine and a large chunk of the people taking this drug is not presented in its clinical trial, there is an immediate, serious risk that those medicines may not be active in those people.”

Unfortunately, a lack of diversity in clinical trials remains a recurring problem, with no sign of significant improvement. According to Li, this document creates awareness in the industry but does very little to resolve this large-spread issue.

Because the recent FDA guidance fails to include incentives or consequences, Li noted that the recent FDA guidance on clinical trial diversity does not go far enough to deliver real change in US clinical trials.

According to Li, “achieving diversification is not something the FDA or pharmaceutical industry can do alone.”

“It is not realistic nor sufficient. However, that does not mean the industry cannot act, meaningfully and substantially, to improve the issue at hand.”

Where Do Clinical Trial Disparities Begin?

Diversity in the healthcare system means that all backgrounds, beliefs, ethnicities, and perspectives are adequately represented in clinical trials. Still, US medical schools are struggling to keep pace with the nation’s more racially and ethnically diverse population.

Rising educational costs are also partly to blame for the lack of a more diverse medical workforce. In 2019–2020, the median cost to attend a four-year public medical school was $250,222, with private school costing around $330,180, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“From the start, the composition of US medical students is not the best representation of our society,” Li highlights.

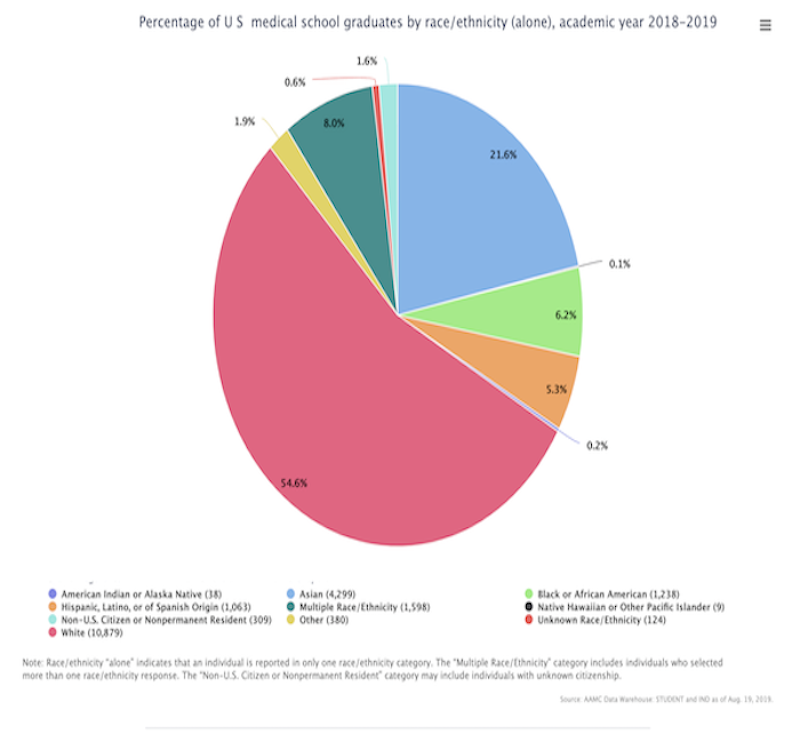

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges data regarding the percentage of racial/ethnic groups for 2018 to 2019 graduates, the largest proportions of medical school graduates were White (54.6%), Asian (21.6%), and Multiple Race/Ethnicity (8.0%) individuals.

A Viewpoint in the AMA Journal of Ethics states that “although the combined percentage of people in the US from African American, Native American, and Hispanic backgrounds is 31%, only roughly 15% of current medical school applicants, 12% of medical school graduates, and 6% of practicing physicians are from these ethnic backgrounds.”

By the year 2050, Pew Research Center data indicates racial and ethnic minority populations in the US are expected to comprise roughly half of the US population, with underrepresentation in the medical school system likely to worsen if left unchecked.

“Patients like to visit doctors that look like them. That’s just human nature. When recent graduates enter society and build their patient base to refer to trials, they often lack patient diversity, which adds another layer of complexity,” Li emphasized.

In the US, 28% of physicians and surgeons are immigrants of color, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This reality speaks to the mounting issues of systemic oppression — minority groups who faced oppression since this country’s founding are much less represented as physicians.

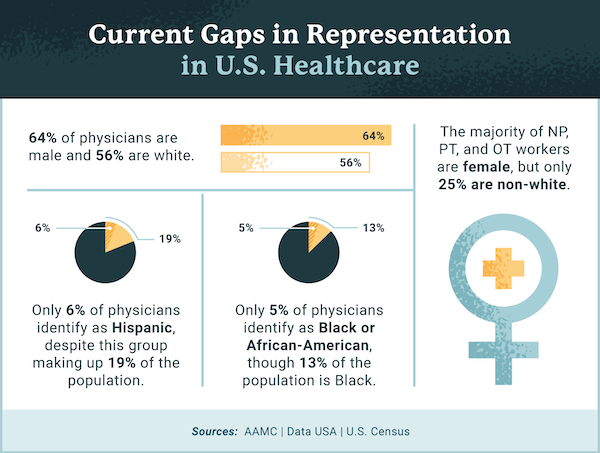

The Association of American Medical Colleges found that roughly 36% of active physicians are female. Additionally, only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite making up 13% of the US population. Fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic or Latin American, despite Hispanics comprising 19% of the US population.

Are Decentralized Clinical Trials the Answer?

In recent years, decentralized clinical trials have gained popularity and may be an effective tool to bolster greater clinical trial diversity and inclusion. Virtual clinical trials can allow patients to be monitored at home to collect real-time data throughout the participant’s daily life, but even digital technology has its limitations.

Li warns that decentralized clinical trials could widen the medical distrust eroding the public’s confidence in the healthcare community.

“It is important to understand the advantages and disadvantages associated with decentralized clinical trials and understand that not all clinical trials are going to be decentralized,” said Li.

“Virtual clinical trials are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, these trials will potentially increase the participant pool and, as a result, include previously unreached parts of the US population,” he continued.

On the other hand, Li explained that virtual clinical trials could potentially alienate the patient population that craves human-to-human clinical interactions.

From 2019 to 2021, the number of decentralized/virtual clinical trials involving mobile healthcare more than doubled.

“The human care factor cannot be virtualized and should not be virtualized. The patient’s trust in the medical staff is based on human interactions,” Li clarified.

If the human element is removed altogether, the medical distrust issue among patients may exacerbate and intensify this problem.

In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 74% of Americans said they had a mostly positive view of medical doctors, while 68% had a mostly favorable view of medical research scientists who conduct research to investigate human diseases and test methods to prevent and treat them.

Healthcare providers, pharmaceutical companies, and government organizations all have a growing responsibility to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, not only for their employees but also to better serve patients.

“These industries should be more proactive, instead of waiting for other parts of society to move,” he emphasized.