Khunatorn - stock.adobe.com

What is the chronic care model (CCM) in healthcare?

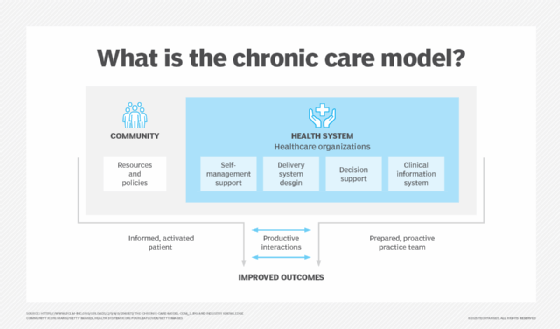

The chronic care model considers both social and health system factors that influence a patient's clinical outcomes and disease progression.

Healthcare organizations looking to bend the healthcare cost curve are increasingly focused on their sickest, most expensive populations, bringing the chronic care model, or CCM, to the forefront.

Indeed, chronic illness drives the bulk of the nation's healthcare costs. According to the CDC, the U.S. sees a whopping $4.5 in annual healthcare expenditures. Some 90% of that is spent on people with chronic and mental health conditions, including the following:

- Heart disease and stroke.

- Cancer.

- Diabetes.

- Obesity.

- Arthritis.

- Alzheimer's disease.

- Epilepsy.

- Tooth decay.

Most healthcare leaders agree that a focused chronic disease management program is essential for treating these populations, controlling health outcomes and potentially preventing further illness.

"Chronic disease management (CDM) programs are proactive, organized sets of interventions focused on the needs of a defined population of patients," as defined on the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps website.

Although most CDM programs share a few evidence-based practices -- patient education, healthy behavior coaching, patient self-management and peer support -- there is no one-size-fits-all approach to chronic disease management.

In recognition of that, the CCM exists to guide healthcare organizations and outline key tools and processes they need to achieve better outcomes among their chronically sick patients.

Designing the CCM

The CCM was developed in 1998 by Edward Wagner, M.D., and colleagues at the MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation.

"The Chronic Care Model (CCM) identifies the essential elements of a health care system that encourage high-quality chronic disease care," according to the Center for Accelerating Care Transformation (ACT Center). "The Chronic Care Model can be applied to a variety of chronic illnesses, health care settings, and target populations. The bottom line is healthier patients, more satisfied providers, and cost savings."

The CCM considers factors both inside and outside the hospital or clinic, acknowledging the way in which health system operations and community and social factors influence an individual's health and well-being.

Under a community pillar, Wagner and colleagues describe how resources and policy can affect individuals, particularly their own chronic care self-management.

The health system pillar looks at the care delivery system, clinical quality and decision support and the health IT or clinical information systems that support providers.

The chronic care model hinges on the concept that an informed, activated patient working with a prepared, proactive clinical team will have productive healthcare interactions.

Community

The community aspect of the CCM acknowledges the role an individual's surroundings play in chronic disease management. This includes schools, government, nonprofits and faith-based entities, to name a few.

These entities have the potential to reinforce health system efforts, Wagner and colleagues say. For example, access to green space or walkable communities can support individuals managing their illnesses with physical activity. Conversely, attending a school with no subsidized meals or meals with little nutritional value can hamper disease management.

The CCM dictates that healthcare organizations and providers should encourage patients to participate in relevant community programs. Additionally, organizations can form community-based partnerships to create a better on-ramp for patients in need of community engagement. Hospitals and health systems might also use their community influence for advocacy efforts, such as advocating for walkable communities or healthier school lunches.

Researchers have begun to identify which community factors most support CCM. In 2021, investigators surveyed both patients and clinical leaders and found that factors like food access, public space and recreation, proximity to healthcare providers, social services, educational resources, transportation, housing and arts and culture were all influential in CCM programs.

Moreover, the researchers said that linkages between social goods and healthcare providers, specifically community health partnerships, were essential.

However, providers still find themselves limited in connecting patients with community-based organizations, often because health-related social needs are complex and manifold. For example, a provider might successfully refer a patient to a food bank, but the patient might live in a shelter without the requisite appliances to prepare meals.

Finally, the researchers acknowledged the role that structural issues outside the realm of health systems and social services. Problems like institutional racism and economic inequality adversely affect efforts to practice CCM. Addressing these issues is an uphill battle, the researchers acknowledged, but beg the role of health systems and community organizations as social advocates.

Health system

On the health system level, Wagner and colleagues discussed the practice or system design that supports CCM.

This means having a business model that supports CCM as well as clinician leaders who are enthusiastic about CDM strategies.

Moreover, the health system supports patients across the care continuum, engages in change management and quality improvement projects, provides incentives based on quality of care and practices strong care coordination across organizations and providers.

Notably, health systems operating under a CCM have a high-reliability culture and culture of patient safety. They openly and transparently handle medical errors and safety events, Wagner and colleagues said.

Self-management support/education

In addition to the health system and clinicians delivering care, Wagner's CCM considers the role of the patient, particularly in terms of patient self-management. This refers to patients' ability to manage their own health and their empowerment to do so.

Healthcare providers fostering self-management need to focus on goal-setting and motivational interviewing, while stressing the role the patient plays in their own health. Ensuring patients have the knowledge and tools necessary for that self-management, including patient education and high- and low-tech patient engagement tools, will also be key, according to Wagner and colleagues.

Most experts agree that patient self-management is not easy. This is because it can be challenging to influence how a patient behaves and takes care of herself outside the clinic or hospital. To that end, patient education is key, but it needs to be supplemented with patient-centered care.

"In clinical settings, self-management support goes beyond simply supplying patients with information," according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. "It includes a commitment to patient-centered care, providing comprehensive patient education, creating a clinical team composed of clinicians and administrative staff with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, and using office systems to support follow-up contact and tracking of patients."

In addition to patient education, healthcare providers need to consider the tools and technologies that help patients manage their own care, such as the following:

- Remote patient monitoring tools.

- Wearables.

- Digital treatment reminders.

- Medication management and reminder tools.

These tools, coupled with adequate information about one's own health and strong patient motivation, might help patients support themselves outside the clinic or hospital.

Delivery system design

In addition to patients' ability to care for themselves, the CCM dictates that patients need adequate access to a well-designed healthcare delivery system to see optimal disease management.

For example, health systems need to make enough appointments available to provide high-touch care management, while also allowing health systems to adequately manage their resources.

Additionally, hospitals and health systems following the CCM need to create mechanisms for supporting team-based care, evidence-based care, clinical case management for complex patients and regular follow-up messaging and care. Focusing care teams on longitudinal care management and not just acute care will be central to building overall well-being in patients.

This will require strong care coordination among the various providers -- and the patient -- involved in the care management plan, according to the Rural Health Information Hub (RHIhub).

"Care coordination models seek to streamline care strategies and coordinate communication among providers to minimize disease progression and improve quality of life," RHIhub says on its website. "Successful care coordination requires effective collaboration among care team members and between the care team and the patient."

Because chronic care management requires a multidisciplinary care team often helmed by primary care providers, disease-specific specialists and sometimes case managers, coordination is key.

Healthcare providers need the tools and systems necessary to communicate with one another to ensure continuity of care plans across settings. Communication through patient portals, EHRs, health information exchanges (HIEs) and telehealth can help connect disparate providers caring for the same patient, according to RHIhub. These care coordination services are often reimbursable, RHIhub added.

Delivery system design needs to consider the patient, Wagner and colleagues noted. Providers must ensure patients both understand their care plans and agree that they fit patients' cultural or personal needs and preferences.

Decision support

Decision support refers to the treatment plans crafted to manage chronically ill patients, Wagner's CCM states. This includes care and treatment plans that are evidence-based, consistent with data and supportive of patient preferences.

Notably, this means organizations need to make it easy for providers to access the latest evidence-based guidelines and continuing medical education.

Predictive analytics tools are making chronic care management easier. For example, providers can use predictive analytics to determine biological and socioeconomic risk factors to promote chronic disease prevention and determine disease management strategies.

Other tools are using AI to analyze chronic disease progression, allowing healthcare providers to better predict disease outcomes and tailor interventions before adverse outcomes come to bear.

Care coordination and integration with specialists are also essential. While primary care providers at larger health systems might have the tools to connect with specialists as necessary -- in fact, some might practice within the same facility -- telehealth has proven effective in this area.

The technology lets disparately located healthcare providers connect and consult on a given patient case, ideally enhancing the level of care given to the patient. As always, technology integration is key to allowing providers to leverage the data necessary to understand a patient's case.

Clinical information systems

Finally, this element of the CCM refers to the ability to manage, use and make sense of data that facilitates efficient and effective care, according to Wagner and his team.

Health systems need data to know who has a chronic illness and learn more about those populations, the group stipulated. Using population health tools and data analytics systems, organizations can segment out chronically ill patients by disease state and create targeted and tailored interventions.

In addition to data analytics and other information systems, health systems operating under a chronic care model need tools to provide timely information to patients and providers, identify subpopulations and practice population health, enable care planning, share information for care coordination and monitor provider performance.

Health IT interoperability will be critical. As providers utilize a vast amount of patient data and disparate care management systems, IT integration will enable a more seamless clinical experience for providers and patients alike. Interoperable EHR systems and HIEs will enable teamwork across providers.

Meanwhile, IT integration for RPM tools, wearables and other patient-facing systems, such as patient portals or appointment booking tools, will create a better digital patient experience. Through a better digital experience, patients might be more likely to continue engaging with their health and providers.

Integrating goal-oriented care

In the decades that have passed since the creating of Wagner's CCM, some healthcare experts have added to the model. In particular, elements about patient motivation have come front and center as the medical industry further embraces patient-centered care.

"Person-centered care views medicine as promoting a person's 'life project' by focusing on the whole person instead of their disease(s)," according to an article in the journal The Patient. "It begins with the individual as a person and requires a strong therapeutic relationship between the clinician and the person."

To that end, the researchers urged healthcare providers practicing under the chronic care model to integrate patient-provider communication skills like motivational interviewing and shared decision-making to personalize a chronic care plan. This is called goal-oriented care, the researchers said.

"Goal-oriented care is an approach to person-centered care in which the focus is on what matters most to the person seeking care over the course of their life," they explained. "It uses the person's goals to inform care decisions, which are arrived at collaboratively between clinicians and the person."

Most patient goals can fit into the following categories: prevention of premature death and disability, maximization of quality of life, optimization of personal growth and development, and experiencing a good death. However, the researchers said that goal-oriented care is not one-size-fits-all, meaning goals might not fit perfectly within a single category.

Still, goal-oriented care can help create greater motivation for patients, which can be key for adherence, the authors said.

Take, for example, a woman with poorly controlled diabetes. The CCM alone would suggest she start daily walking to reduce her HgbA1c. By adding in a goal-oriented approach, the care team might discover that her poorly controlled diabetes causes fatigue, discouraging her from daily walking.

That knowledge could prompt the care team to adjust medications to better control blood sugar, reducing feelings of fatigue and making it easier for her to walk with her friends.

In another example, the authors described a man whose medications cause hand tremors, getting in the way of his love for painting. Although the dosage is evidence-based, it gets in the way of quality-of-life goals. With this knowledge, clinicians might adjust medications to help meet overall life goal achievement instead of just disease-management targets.

After all, chronic disease management is about boosting clinical outcomes while meeting patients where they are. Results are not achieved with care plans to which patients can't adhere.

The CCM creates a framework for healthcare organizations facing the dual priorities of improving chronic disease outcomes and promoting patient-centered care. By understanding the social context of a patient's health and well-being and designing a health system supportive of better outcomes, hospitals and clinics can boost chronic disease management.

Sara Heath has been covering news related to patient engagement and health equity since 2015.