Getty Images

How to Write Open Clinical Notes for a Good Patient Experience

Open clinical notes that are empathic, informative, and rely on objective clinical information are most likely to yield a good patient experience.

There is a new compliance mandate in healthcare, one that despite all of its good intentions for patients is leaving some providers worried about the healthcare experience. Requirements for open notes and patient access to clinical notes, as spelled out in the 21st Century Cures Act, are a new spin on an on old philosophy leaving healthcare providers balancing clinical documentation with a good patient experience.

Long before it was a compliance issue, open clinical notes was a key philosophy in the healthcare industry. The practice’s main advocacy organization, OpenNotes, has been around for over a decade, with the exercise of sharing open clinical notes becoming particularly popular around the meaningful use days.

Meaningful use, or the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs, asked healthcare providers to enable patient data access, usually via a patient portal, as part of regulatory compliance.

Although that access did not pertain to open clinical notes specifically, it did spark a vast movement toward patient engagement that largely hinged on transparency and communication in healthcare.

“We decided as a policy, that we would make all of our consult notes immediately available to the source patient and any involved family members,” said Stephen O’Neill, BCD, JD, a mental health specialist and bioethicist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School. As an open notes pioneer, O'Neill started sharing clinical notes nearly 30 years ago.

“We found that it was so beneficial because patients and their significant others felt like we weren't hiding things from them, that we put it right out there,” O’Neill told PatientEngagementHIT. “And oftentimes I would show a draft of my note even to the family or to the patient, to make sure that I had captured their perspective accurately.”

Previous studies of OpenNotes have repeatedly found patients are more engaged when they look at their clinical notes, one of the reasons why some clinicians like them. In a May 2021 Journal of General Internal Medicine study, 50 percent of clinicians first trying open clinical notes ended up saying their patients took better care of themselves when given access. About three-quarters of providers said they saw better patient empowerment.

Meanwhile, a 2019 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that open clinical note access improved medication adherence for 14 percent of patients.

Access to clinician notes helped 64 percent of patient respondents better understand why their clinician prescribed a certain medication, and another 62 percent felt more in control of their medications. Fifty-seven percent of respondents said they were able to find answers to questions they had about their medications, saving them a call to their doctors.

As part of the 21st Century Cures Act, HHS and ONC included sharing of clinical notes as part of the ONC information blocking rule. Open clinical notes can empower the patient, HHS reasoned, and should be included as a form of data prohibited from information blocking.

“From the start of our efforts to put patients and value at the center of our healthcare system, we’ve been clear: Patients should have control of their records, period. Now that’s becoming a reality,” Alex M. Azar, then-HHS Secretary, said in a March 2020 public statement announcing the final information blocking rule.

“These rules are the start of a new chapter in how patients experience American healthcare, opening up countless new opportunities for them to improve their own health, find the providers that meet their needs, and drive quality through greater coordination.”

But with every Medicare provider now responsible for allowing patient access to clinical notes, there’s the potential for a can of worms to open. A patient might not like what she sees in her clinical notes, increasing the urgency for learning how to write a good open note for a positive patient experience.

Crafting a patient-centered clinical note

Writing out a good clinical note isn’t going to be the most cumbersome part of clinical documentation, according to Leonor Fernandez, MD, a physician with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an open notes researcher.

But it might take a little finesse.

Healthcare providers who have never before shared their clinical notes with patients might need to prepare for a little bit of tweaking to make sure their notes are understandable for the patient, and should get ready for a little bit more discussion with patients newly empowered with their medical data.

While Fernandez said this might only require a slight adjustment, it will be helpful to be aware of the key issues that crop up when patients do comment (something Fernandez ardently maintained is a rarity).

Choosing what to say

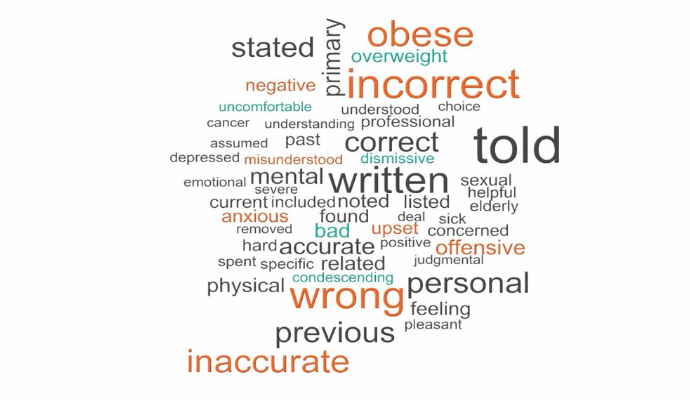

Words matter, and according to Fernandez, that idiom extends to clinical consult notes. In recent research published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, Fernandez and colleagues uncovered certain verbiage or phrases that can be off-putting to patients reading their clinical notes.

To be clear, the researchers found only about one in 10 patients ever found something offensive or judgmental in their clinical notes, Fernandez cautioned as a caveat. Nevertheless, it is important to understand where or how things went wrong for that one patient.

In a lot of cases, it came down to word choice. Words like “incorrect,” “obese,”

“wrong,” “anxious,” “depressed,” “inaccurate,” or “elderly” came up fairly frequently as unfavorable to patients.

“It was a mixture often of tone, and of feeling in some way dismissed or disrespected, or misunderstood,” Fernandez said.

For example, patients tend not to like to read that they “denied” something in the medical encounter, especially when it comes to subjective pain. That word choice might make the patient feel invalid or dismissed, Fernandez said, which can be particularly upsetting for patients who regularly struggle with a medical issue like chronic pain.

Overall, patients tended not to like reading about diagnoses that were not discussed during the medical encounter, phrasing that seemed condescending, or words that labeled them negatively, Fernandez and team also found. This was particularly true for traditionally marginalized populations that already have low patient trust in the medical establishment.

Most of that more negative wording shouldn’t be too strenuous to cut out, according to CT Lin, MD, a clinician at UC Health who has been sharing his clinical notes since the early 2000s. After all, that kind of language isn’t very acceptable for medical—or any—discourse.

“Pejorative wording is worth consciously changing because it's frankly never appropriate anymore,” he told PatientEngagementHIT. “‘Highly anxious, drug-abusing patient,’ or, ‘patient refuses to do this.’ Well, there's an underlying reason to the refusal. Figure that out, and then you can say, ‘Patient has had trouble affording their medications.’"

And as far as what Lin called “misunderstood wording”—words like “obese”—he said using more objective clinical language could be helpful. These words have become stigmatized, he said, but providing the medical context for them can help patients better understand them.

“Morbidly obese—it's still objective, but because it has a cognate in layman's terminology, maybe that's a terminology we have to leave behind, for example,” Lin offered. “Maybe medically obese, or BMI greater than 40, maybe synonyms that are more objective.”

Medical providers do not need to view reworking their phrasing as a burdensome endeavor; according to Fernandez, it is most helpful to consider how the provider would communicate with the patient face-to-face when writing the clinical note. In doing so, clinicians might lean on the interpersonal skills they deploy during in-person encounters that yield positive experiences.

“I try and mirror the concept of what would it feel like if I was reading this out loud to the patient,” Fernandez explained. “If I might wince and really substantially change the terms, because otherwise I feel they might be offended, then I shouldn't write that. We do this all the time when we talk to a patient in the room. We hopefully pick our words so that they're a little more meaningful, so that they're a little more affirming of the patient's strengths and what they're trying to do, or their fears.”

Addressing negative patient feedback

None of this is to suggest Fernandez doesn’t say what she needs to say clinically; she and others who advocate open clinical notes asserted it is important to stand by a clinical diagnosis. But it is the philosophy of collaboration and transparency that is important in clinical note sharing.

Lin said it is important to hear a patient out when she does not agree with an objective clinical statement. He usually offers to include her comments in the clinical note, but affirms that he cannot change his assessment if it is factually accurate.

“We had one patient complaint from the 100-patient cohort, and that was basically, ‘I don't want you to mention alcohol in relation to my heart disease.’” Lin said, detailing results from open notes testing at his own organization.

“And the physician's response was, ‘It's medically accurate. I'm not changing it.’ And our offer to the patient was, ‘We're happy to include your comment, but the physician's note is accurate. We're not changing it.’"

Open clinical notes and behavioral health

Many clinicians faced with open notes requirements might view the behavioral health space as somewhat hairy. After all, behavioral health has been highly stigmatized, highly segregated from the physical health space, and can be highly inflammatory for some patients, as Fernandez’s data revealed.

But it’s also highly important for patient wellbeing, according to Lin, and as long as it was discussed during the medical encounter, it warrants a place in consult notes.

“Some providers think, ‘Oh, I can't mention depression,’” Lin said. “Well, if you talked about it, there's no reason you can't mention it in your note. It's an accurate reflection of your conversation. It's only if you didn't say anything and then you decided to put in your note, that could be a problem. And that's skills-building on the physician side.”

According to Stephen O’Neill, the mental health specialist from Harvard Medical Center, there indeed are important caveats to consult notes in the behavioral health space.

For one thing, not every patient in the behavioral health space should actually get access to their clinical notes. There are some exceptions ONC recognizes in behavioral health that disqualify providers from having to disclose consult notes.

For example, a patient who experiences domestic violence at home might not benefit from clinical note access. That violent partner could access the note, creating a more dangerous situation, O’Neill explained.

Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) likewise might not benefit from open clinical note access.

“When a patient with PTSD is reading about the traumatic event that they encountered and reading that in our notes, it becomes a recapitulation of the event itself,” O’Neill said. “And so, they sometimes feel re-traumatized. For us clinicians, we oftentimes write down a lot of the lurid details of the trauma, whether it's a rape trauma or whether it's a war issue or whatever it might be.”

This requires a deep in-person conversation with the patient about the best strategy for her own wellbeing, O’Neill recommended.

“We have to think about talking with the patient about when is it beneficial for them to read the note, and make sure that they have good supports, or that they understand that they might get upset or more anxious,” he advised. “So maybe they should read the note only just before they're coming back to the next therapy session, for example.”

But again, that does not mean he filters his language, although he does understand the impulse. After all, when O’Neill started offering consult note access, he was afraid some of his own patients might fall apart seeing the clinical notes.

But that wasn’t the case, he soon found.

“When patients read their notes, they generally benefit a lot because what they really are looking for is, is there concordance between what I've said in the office and in fact written in a note,” O’Neill explained.

To avoid negative reaction, O’Neill makes sure he levels with the patient and explains that clinical documentation is a compliance requirement. For example, he must note mental status of all of his patients, which includes whether the patient is homicidal or suicidal. That could be jarring to the patient, O’Neill recognized, so he ensures he explains that the language will appear and what it means.

Combatting clinician burnout

As with any compliance issue, the clinical note sharing requirement has elicited another question from clinicians: how much work will this be?

That’s a reasonable question, the experts agree. After all, clinical documentation and EHR time trumps patient engagement two to one, seminal research from the American Medical Association has found.

“This information blocking federal rule has occurred at the same time that there is an epidemic of physician burnout,” Lin pointed out. “We are already in the middle of this idea that physicians despise their electronic health records.”

It can feel like an uphill battle for healthcare organizations already dealing with EHR-related issues to now ask providers to also share their clinical consult notes. But this is a compliance issue, and even the most outspoken of critics are warming to the idea of open clinical notes.

Lin said some of this begins with provider education at the facility-level. Healthcare organizations should issue simple guidelines that can help providers adapt their language in their clinical notes. For their part, clinicians might want to post reminders next to their computers to fulfill this patient experience need.

There is also the possibility of opting out, Lin noted, but that’s a nuclear option he urges providers not to test. It may be more trouble than it is worth to produce a valid reason for opting out of open clinical notes, he suggested.

Is this much ado about nothing?

At the end of the day, not a lot of patients are actually going to be bothered by these open clinical notes, Fernandez predicted. After all, even her own study, which sought to identify the worst parts of an open clinical note, didn’t yield a lot of patient complaints.

“I mostly get almost nothing as response from my patients,” she said of her own clinical note sharing. “When they do comment, they often comment how great it is that they can read it.”

The data corroborates that, showing provider fears are proving mostly unwarranted. In May 2021, data in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that even the most ardent of detractors are starting to warm to the concept of open clinical notes. The study of about 200 clinicians showed that 44 percent changed their minds about open notes after adopting the practice.

Meanwhile, 2020 data from OpenNotes itself found that 96 percent of patients understand all of their clinical notes, negating fears that patients won’t understand the medical jargon or misunderstand clinical terms.

Those more tepid patient responses could be the credit of writing a good open note, one that is understandable, clear, concise, and empathic or free of judgmental language. This can take some fine-tuning. But by making a few adjustments to vocabulary, being mindful of patient-centeredness and empathy, and sticking to patient satisfaction principles practiced during in-person care, healthcare providers can craft a good open note.

And in doing so, they can promote patient empowerment and education, while also fulfilling regulatory requirements.

Correction 06/29/2021: A previous version of this article misstated the number of years OpenNotes has been in operation. Additionally, it misstated Steven O'Neill's credentials.