Getty Images/iStockphoto

How Healthcare Is Starting to Heal Damaged Black Patient Trust

A history of racism in medicine and implicit bias tainting patient-provider communication has resulted in a significant barrier to Black patient trust.

2020 has been defined by more than just COVID-19. For many, it’s been a year of uncomfortable truths, of acknowledgment and unlearning of implicit biases. In healthcare, 2020 has pushed providers to ask themselves tough questions, like why Black people are getting sicker than their White counterparts, and if institutional barriers and a checkered history are what has dampened patient trust.

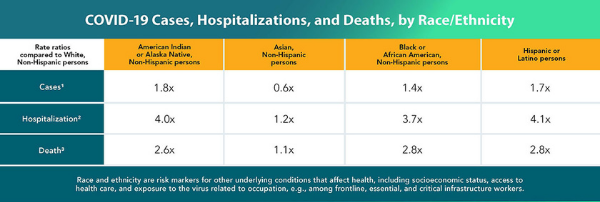

It started with a slow burn, with scientists observing higher rates of COVID-19 infection and death among Black, Hispanic, and Alaska Native/American Indian (AN/AI) populations than in White people. In the early aughts of the pandemic, this came to the forefront through anecdotal evidence, with leading industry groups calling for more data regarding the virus spread among different racial groups in April.

By the end of May, the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) could definitively say Black patients experienced COVID-19 infections and deaths at a higher rate than White patients, although that report did come amid industry scrutiny for being thin at best.

By November 2020, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) had reported that Black patients were three times more likely to die from COVID-19 than White people. These reports sparked industry efforts to understand the institutional limitations that cause these and other racial health disparities.

And then, in a video seen around the world, the nation bore witness as George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was killed by Minneapolis police officers. What came next was a wave of racial protests across the country and a national reckoning on race and racism.

In medicine, providers and clinical leaders looked deeper than institutional barriers causing COVID-19 racial health disparities, because in reality these disparities existed long before the virus. For example, Black women are more likely to die due to complications with pregnancy or childbirth than their White peers, leading the United States to some of the worst maternal health disparities in the developed world.

Per figures from the HHS Office of Minority Health, Black people are also 60 percent more likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes by a physician than non-Hispanic White patients. In 2016, Black adults were 3.5 times more likely to have end-stage renal disease (ESRD) than White patients.

Most experts agree that these disparities are the result of health inequities, not biological differences between Black and White people, or people of other races. Factors like access to care, the social determinants of health, and structural racism have all shaped the way Black people interact with the medical establishment.

Each of these issues is its own complex theme, deserving of its own study and list of policy solutions. But they are also woven together, stemming back to a history of racism and the way it has shaped centuries of medical practice. Overwhelmingly, that history has affected patient trust, a crucial component of the patient experience that when established, can result in meaningful patient-provider relationships and strong patient activation.

The trouble, experts are beginning to argue, is that patient trust isn’t exactly a given among Black communities. In some cases, trust isn’t there at all.

Trust as the foundation of positive healthcare interactions

According to Danielle Brooks, JD, a lawyer and the director of Health Equity at AmeriHealth Caritas, trust is so essential to the healthcare encounter because healthcare is so very personal.

“You are really exposing yourself by talking about your history, habits, family, everything,” Brooks told PatientEngagementHIT in an interview. “And so, having a space where you can fully trust and fully be yourself to get the best care is really essential.”

Trust has become even more important as healthcare explores new models of care, like patient-centered care and whole-person care.

“Those paradigms really rely on that linchpin of patient trust to be able to give that type of care that's personalized, that's well coordinated, and that's high quality,” Brooks added.

But some communities, like communities of color, haven’t been able to experience strong patient trust, Brooks said. Black and Brown patients aren’t always able to go into a medical encounter and feel like their provider will respect them or truly listen to their concerns. It’s those issues that are causing some racial health disparities, Brooks remarked, and that eroded patient trust even prior to the pandemic.

“Members of marginalized communities already know that barrier is to convince that person that you are of their same level and to be able to receive care,” Brooks stated. “There's a cognitive, or at least a subconscious recognition of those marginalized people, that when you do walk into a situation, part of that identity is going to be judged upon. So I wouldn't say that the trust has been there.”

Lack of patient trust can have negative consequences. As Brooks noted, poor trust can devolve into racial health disparities. It can also discourage access to care, medication adherence, or access to key preventive services like vaccinations.

As healthcare works to rebuild that trust and to close growing health disparities, it must put its current challenges into historical context.

The history of medical racism, abuse of Black and Brown bodies

To understand the historical roots of mistrust among Black and Brown communities, one must understand the historical roots of medical racism, according to Brooks.

“There's a very good reason that historically marginalized communities do not trust the medical system,” she said. “And it's because of this history.”

Dating back to 1619, when most historians agree the first enslaved Africans were forcibly brought to North America, people of color were not regarded the same as White people medically.

“If you look at Darwinism and even previous schools of thought, there were concepts that different races evolve from different species. And they really did use the medical society to rationalize the dehumanization of other populations,” Brooks explained.

That itself is a difficult scar to erase, Brooks explained, but the abuse of Black and Brown bodies that stemmed from those schools of thought exacerbated that damage.

Throughout slavery, White doctors used Black and Indigenous slaves for medical experimentation. Notably, the “father of gynecology” J. Marion Sims experimented on Black female slaves without anesthesia, which was not yet widely used. Sims rationalized the practice because the medical establishment at that time did not believe Black people felt pain the same way as White people.

That thought process would last throughout parts of the 20th century, when medical students would experiment on Black people because they did not believe they felt severe pain, Brooks said.

Even after emancipation, the way the medical industry regarded Black people was dangerous for their healthcare. After reconstruction, there was rampant illness among recently emancipated enslaved people, Brooks said.

“But it’s even further more interesting because they did start to move for public health to support the newly emancipated people, but there was also a theory that African Americans weren't really equipped to live in freedom, and that's why they were dying,” she explained.

These mindsets—that Black people did not feel pain the same way as White people, that they were genetically inferior, that they were “simple” or not fit for freedom—would lay the groundwork for centuries of abuse at the hands of medical professionals.

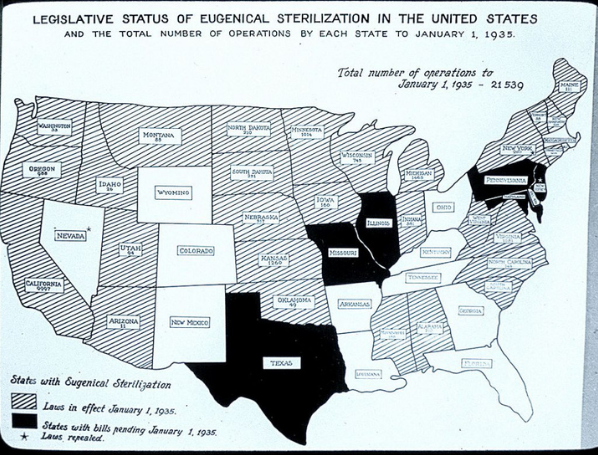

And while that abuse was felt regularly on a micro-scale, it culminated in two serious stains on the US health system: eugenics and the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. To be clear, these two events do not represent the full extent of serious medical racism. However, they do offer two glimpses into how structural racism has shaped medicine today.

Eugenics and unwanted sterilization

Eugenics is the idea that breeding for more “desirable” traits would make for a better human race. With roots in the late 19th Century Darwinism, the concept would result in a grotesque practice of unwanted or coerced sterilization among “undesirable” populations.

Performing unwanted sterilizations was the medical establishment’s effort to phase out certain “undesirable” characteristics. By performing a tubal ligation or unwanted hysterectomy on a woman—as well as performing sterilization procedures on men—clinicians believed they could stamp out “feeblemindedness,” “criminality,” or supposed sexual promiscuity.

“Eugenics was a commonly accepted means of protecting society from the offspring (and therefore equally suspect) of those individuals deemed inferior or dangerous – the poor, the disabled, the mentally ill, criminals, and people of color,” journalist Lisa Ko wrote in a landmark PBS article.

These claims often targeted traditionally marginalized communities, like Black people, immigrants, the poor, or the disabled.

This practice was codified in the law. By 1935, over 20,000 unwanted sterilizations had occurred, and numerous states had laws allowing them. The Supreme Court of the United States decision in Buck v. Bell allowed for state laws to crop up across the country, resulting in over 65,000 unwanted sterilizations happening into the 1970s.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

Infamously, the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment began in 1932 with the intent to “justify treatment programs for blacks,” according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

The experiment recruited 600 Black men, 399 of whom had syphilis, without informed consent from participants. Researchers told participants they would be treated for “bad blood,” which at that time could informally refer to syphilis, anemia, fatigue, or a number of other issues.

“In truth, they did not receive the proper treatment needed to cure their illness. In exchange for taking part in the study, the men received free medical exams, free meals, and burial insurance,” CDC said.

The study, originally slated to last six months but stretching over 40 years, was particularly egregious because study participants were not given a valid syphilis treatment, penicillin, once the drug was proven effective and approved for treating the illness.

Following a July 1972 Associated Press story shining light on the Tuskegee study, the HHS Secretary appointed an ad hoc advisory panel to investigate the claims. The advisory panel ruled that study participants had willingly taken part in the research, but that they had done so under false circumstances.

The researchers had misled the men about the stipulations of the study and the participants were unable to make an informed decision. What’s more, the advisory panel corroborated that study participants did not receive adequate treatment as a part of the study.

“The advisory panel found nothing to show that subjects were ever given the choice of quitting the study, even when this new, highly effective treatment became widely used,” CDC explained.

Grappling with a grotesque history

Although the HHS investigation resulted in the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program (THBP), which offered lifetime healthcare benefits to study participants, their wives, and children, the experiment and the long history of eugenics have given rise to serious mistrust among Black communities and the medical establishment.

In the years since, Black patients have grown reticent to visit the doctor unless they experienced serious medical ailments. Black communities frequently discussed issues about grave robbing in which Black bodies would be removed from their graves and sold to medical colleges or hospitals for research, some allege. Rumors would spread among Black communities about so-called Night Doctors, who some believed kidnapped Black people to perform medical experiments.

The medical industry is grappling with these issues today, alongside smaller-scale microaggressions and problems with implicit bias in medicine. And in fact, it’s those microaggressions that may be even more detrimental to good provider relationships among Black people, according to Garth Graham, MD, the vice president of Community Health & chief community health officer at CVS Health.

“It's not just the historical nature to speak a lot of times, it's the legacy of individual interactions with the clinical system,” Graham said in an interview. “It’s the, at the many times challenging, lack of cultural competency that has been present for a long time in communities and how that plays out.”

In other words, limited patient trust among Black communities doesn’t just stem from memories of Tuskegee or eugenics, although those events certainly have left their stain. It’s the word-of-mouth tales about poor healthcare interactions and negative interpersonal exchanges with clinicians that have truly cemented this poor patient-provider relationship.

In October 2020, the Kaiser Family Foundation in partnership with ESPN’s The Undefeated found that Black patients face medical racism that impacts their trust in medicine and may have contributed to racial health disparities.

Thirty-nine percent of Black patients said they have encountered discrimination in the medical setting at least somewhat often, and 31 percent said they experienced discrimination very often. Only 27 percent of Hispanic patients said they experience discrimination somewhat often, and more than half of White patients said discrimination against them happened only rarely.

That discrimination may manifest itself in the quality of care patients perceive they get. More than half (54 percent) of Black respondents said they don’t think doctors provide the same level of care to them as their White peers, and that is part of why Black patients have poorer health outcomes.

In contrast, 42 percent of White respondents said clinicians providing different levels of care quality to White versus Black patients did not account for racial health disparities at all.

These perceptions became a reality for Black patients when the COVID-19 pandemic began in March of 2020. As noted above, Black and Brown people have suffered disproportionately from the virus, and some said that could be due to the pandemic response.

Sixty-six percent agreed the federal response to the outbreak would have been stronger if it were White people who the virus largely affected, the KFF and The Undefeated survey showed. Only 34 percent of the total survey population agreed with that statement, and 42 percent of Hispanic and 25 percent of White patients agreed.

But now, the fight for racial equity in healthcare and beyond is having a moment, and healthcare organizations are looking inward to meet it.

A nationwide racial reckoning

In 2018, New York City officials removed a statue of J. Marion Sims from Central Park.

The move, which came with some protestations from other medical professionals who pointed to the advancements in female reproductive health for which Sims was responsible, was a controversial one. Sims invented the speculum and the Sims’s position for vaginal exams, both of which were groundbreaking for gynecology.

But the removal of the statue was also a step forward in acknowledging and growing from history’s mistakes and forging a new path forward to achieving better health equity.

“He really pioneered some techniques, but through a lot of really terrible, gross torture in these medical discoveries,” Brooks, the lawyer from AmeriHealth Caritas, explained.

And today, in 2020, healthcare organizations are taking similar steps of their own. In the wake of the stark racial health disparities observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a national racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd, healthcare organizations are making calls for more health equity and a dismantling of medical racism.

In September, Intermountain Healthcare, a leading integrated delivery system, committed itself to promoting health equity and unlearning implicit bias and medical racism. In November, the American Heart Association made a similar statement recognizing institutional racism as a key driver of health inequity.

A few weeks later, the American Medical Association doubled down on its efforts to dismantle medical racism.

“The AMA recognizes that racism negatively impacts and exacerbates health inequities among historically marginalized communities. Without systemic and structural-level change, health inequities will continue to exist, and the overall health of the nation will suffer,” AMA Board Member Willarda V. Edwards, MD, MBA, said in a statement announcing the policy.

This is a good thing, Graham said, especially when the healthcare institutions making commitments to unraveling medical racism understand the importance of community partnership.

“The elevation and evolution of the discussion about racism and its impact in health and public health this year is an opportunity. As we, and as others, continue to make commitments, quite frankly, the idea of making sure that we are making local commitments is important because the community will continue to see that,” he explained.

In partnering with local community leaders, those with true understanding of community needs, healthcare organizations can deliver on their promises more effectively and begin to engender trust with traditionally marginalized populations.

“People want to see tangible, impactful things, dealing with the kinds of issues that they're seeing unfold before their eyes, like challenges around food security, challenges around housing insecurity, and the positive things that matter in their daily lives,” Graham advised.

Brooks agreed with this, pointing out that community-based health efforts cannot be reactionary.

“It’s also incumbent to make sure that it's not just reactive,” she said. “There is a bilateral exchange. So that means having the community upfront when decisions are created, and when these ideas, or these programs are generated, so that you are truly creating something that actually responds to the needs of the community.”

Dismantling implicit bias from the inside

But like Graham said, Black patients also remember their poor individual experiences, like the time they felt their provider discriminated against them or spoke down to them. Those negative experiences have significant ripple effects.

Most healthcare organizations know this, which is why they are running diversity, inclusion, and health equity panels and working toward building cultural competency.

These efforts should work, research suggests. In November 2020, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania found that patient experience ratings were higher among Black patients when they visited with a clinician who was also Black. The researchers stated this may be due to shared lived experiences between patient and provider or because the patient avoided implicit bias from a provider of another race.

Part of solving this problem must include getting more Black doctors, nurses, advanced practice providers, and organizational leadership front and center. But to get the kind of results in the Perelman study, organizations will need to deliver on the continuing medical education some have said they are developing around implicit bias.

As healthcare organizations continue to develop and deploy cultural competency programming among staff of all races, Brooks encouraged them to look at the concept from a different angle.

“I actually flip the concept of cultural competency and use the phrase cultural responsiveness,” Brooks explained. “The reason why I don't choose to use the word cultural competency is because the concept of competency is a miss over in the fact that it insights a level of complete in-depth understanding.”

In other words, she said, cultural competency suggests one will know every single thing about every single culture. And while that in itself is completely impossible, there are other downfalls of that framing, too.

“People are just not one part of the aspect of their culture,” she stated. “Most of the times, there's a very intersectional way of living and looking at the world. So it really does come down to responding to the individual need with understanding that background, that experience, and that culture, and how that forms.”

There is no great answer to dismantling medical racism. There is no great answer for building trust between the healthcare establishment and Black, Brown, and other traditionally marginalized communities.

But the current climate is promising.

“When looking at unwinding the issue, it's a marathon,” Brooks concluded. “It's not something that can occur right away, but we can begin to give the tools to providers and professionals and anyone in the health care system to begin to understand how these things present and how they have detrimental impact to the folks that they're serving.”