Getty Images

EFF Warns COVID-19 Tracing Apps Pose Cybersecurity, Privacy Risks

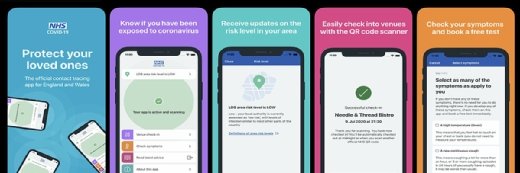

Google, Apple, and others are racing to develop contract tracing apps to help individuals determine potential COVID-19 exposures, but EFF warns the tech may put privacy and cybersecurity at risk.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation are joining the call urging COVID-19 contact tracing app developers to consider the potential privacy and security risks posed by these technologies, while warning no application should be trusted to “solve this crisis or answer all of these questions.”

Earlier this month, Google and Apple announced plans to collaborate on contact tracing technology that would leverage Bluetooth Low Energy to inform individuals whether they’ve been exposed to someone who has COVID-19.

The tech relies heavily on decentralized location or proximity data from mobile phones, which would also alert users to potential exposures. Users are assigned an anonymous identifier beacon, which will be sent to nearby devices via Bluetooth.

When two users who’ve opted into the app are in close contact for about 5 minutes, the devices will exchange their identifier beacons. If either of the users is later diagnosed with COVID-19, the user can then enter their test result into the app and the people who’ve come into contact with the individual (who has also opted into the app), will receive an alert.

The tech giant plans to release the tech in full next month, while Microsoft is also working on similar tech with the University of Washington and UW Medicine, designed to inform public health authorities.

Despite Google and Apple releasing vastly transparent privacy policies, industry stakeholders like the American Civil Liberties Union and about 200 scientists, among others, responded that these apps have the potential to overreach, and developers must ensure proper technical measures are taken to ensure the app is secure.

EFF has now raised similar concerns, focusing on cybersecurity risks. Specifically, the nonprofit advocacy group is worried hackers can target the data sent from the app and undermine the system.

“Any proximity tracking system that checks a public database of diagnosis keys against rolling proximity identifiers (RPIDs) on a user’s device—as the Apple-Google proposal does—leaves open the possibility that the contacts of an infected person will figure out which of the people they encountered is infected,” researchers wrote.

“Taken to an extreme, bad actors could collect RPIDs en masse, connect them to identities using face recognition or other tech, and create a database of who’s infected,” they added.

Researchers are also concerned about Google and Apple’s proposal to have infected users publicly share their diagnosis keys once per day, instead of every few minutes, which could potentially put individuals at risk of linkage attacks.

Here, a threat actor could collect RPIDs from multiple places at once by creating a static Bluetooth beacon in a public place, or by convincing users to install a malicious app. As a result, the tracker would receive a “firehose of RPIDs” at different times and places, and with just an RPID, there’s no way for the tracker to link observations.

In short, the tracker would get many pings with no way of knowing what ping belongs to which individual.

Further, when a user uploads daily diagnosis keys to the public registry, a tracker can use the data to link together all inputted RPIDs from a single day. A bad actor could use this data to link RPIDs together to expose their daily routine, including their address and where they work.

“The risk of location tracking is not unique to Bluetooth apps, and actors with the resources to pull off an attack like this likely have other ways of acquiring similar information from cell towers or third-party data brokers,” researchers explained.

“But the risks associated with Bluetooth proximity tracking in particular should be reduced wherever possible,” they continued. “This risk can be mitigated by shortening the time that a single diagnosis key is used to generate RPIDs, at the cost of increasing the download size of the exposure database.”

For example, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is working a contact tracing tech that would upload the RPIDs hourly, rather than daily.

EFF also warned Apple and Google’s proposal raises inherent risk of cyberattack, as there is currently no way to verify the device sending an RPID. As a result, bad actors could collect RPIDs from other devices and rebroadcast them from their own device.

“Imagine a network of Bluetooth beacons set up on busy street corners that rebroadcast all the RPIDs they observe. Anyone who passes by a ‘bad’ beacon would log the RPIDs of everyone else who was near any one of the beacons,” researchers explained. “This would lead to a lot of false positives, which might undermine public trust in proximity tracing apps—or worse, in the public health system as a whole.”

While Google and Apple have stressed, they’re building the API and intend to allow public health authorities to make the apps, EFF is concerned those agencies will not have the resources to successfully accomplish the task and will need to rely heavily on private sector partnerships.

To avoid these potential risks, developers should rely on a central repository of user data, rather than Google and Apple’s plan to keep the data on a user’s device. And developers should not share any data over the internet outside of what’s necessary, such as uploading diagnosis keys.

Transparency will also be paramount, and apps should clearly state the type of data collected by the user and how to stop the process. Further, users should be allowed to start and stop the data sharing, as well as view the list of RPIDs they’ve received. Individuals should also be able to delete some or all of that contact history.

Developers should publish the source code and documentation to allow users and independent technologists to check their work, while inviting security audits and penetrating testing from verified professionals to ensure security and function.

Lastly, users should not be forced into signing up for an account or service, while the apps should not feature any unnecessary features – including ads. Analytics libraries should not share data with third parties, and developers need to use strong, transparent technical and privacy security measures.

“The whole system depends on trust. If users don’t trust that an app is working in their best interests, they will not use it. So developers need to be as transparent as possible about how their apps work and what risks are involved,” researchers explained. “Insufficient privacy protections will reduce that trust and thus undermine the apps’ efficacy.”

“All of this will take time. There’s a lot that can go wrong, and too much is at stake to afford rushed, sloppy software,” they concluded. “Public health authorities and developers should take a step back and make sure they get things right. And users should be wary of any apps that ship out in the days following Apple and Google’s first API release.”