Getty Images/iStockphoto

How Many Emergency Department Visits are Really Avoidable?

How much of a problem are avoidable emergency department visits for health systems looking to reduce unnecessary utilization?

Reducing emergency department utilization is a top goal for many population health management and value-based care initiatives, but how many trips to the ED could actually be classified as “avoidable” in the first place?

According to a new large-scale study from the International Journal for Quality in Health Care, the rate of unnecessary ED visits may be as low as 3.3 percent, calling into question the value of focusing too many resources on diverting patients into other forms of care.

“The rhetoric surrounding ‘avoidable’ emergency department visits in the United States has been contentious,” wrote authors Renee Y. Hsia and Matthew Niedzwiecki from the UCSF Emergency Department and Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies.

The study notes that estimates of avoidable ED visits vary drastically from about 5 percent to 90 percent, leaving policymakers with little consensus to use as a basis for developing best practices.

Unnecessary ED utilization has often been viewed as an issue of socioeconomics: a way for patients without established primary care relationships – or the means to pay for them – to receive guaranteed care for any issue that arises.

In 2011, nearly one-fifth of patients who visited an ED but were not admitted to the hospital were uninsured, AHRQ found, while 29 percent were Medicaid beneficiaries.

Since 2005, many Medicaid programs have implemented mandatory cost-sharing programs for non-urgent ED visits in an effort to reduce improper use of facilities designed to treat trauma patients and true emergencies.

But “defining what is ‘non-urgent’, ‘unnecessary’ or ‘inappropriate’, is perhaps the first problem,” the authors pointed out, “as these terms are often conflated due to the lack of a consensus for a standard definition of a non-urgent visit and the complex nature of its categorization.”

Current methodologies often rely on suspect data to define whether or not a visit is necessary or appropriate, assert Hsia and Niedzwiecki. Claims data can be misleading, because physicians will conduct a thorough examination for anyone who arrives at the ED, regardless of whether or not the tests and procedures ultimately reveal an underlying medical issue.

In a fee-for-service environment, claims for services that do not result in a definitive diagnosis will look almost identical to those with a more acute clinical outcome.

In order to provide policy makers with a baseline for future decision-making, the researchers decided to use data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) to take a very narrow view of what defines an avoidable emergency department visit.

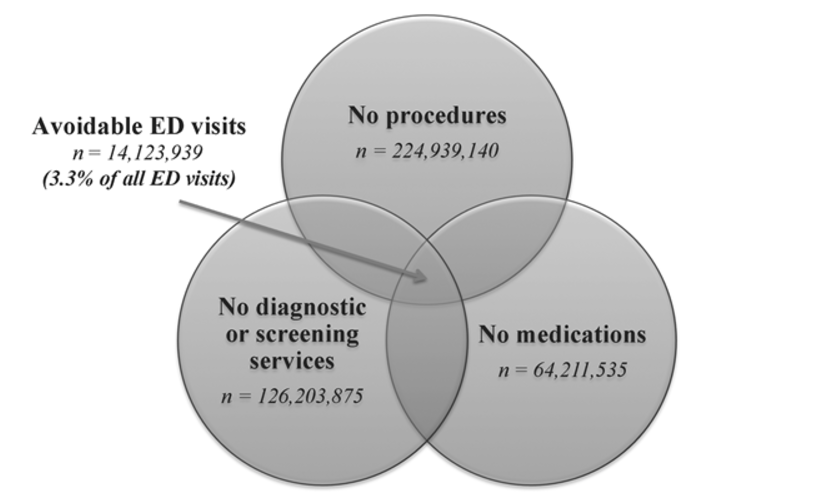

“We conservatively defined ‘avoidable’ ED visits as discharged ED visits not requiring any diagnostic tests, procedures or medications,” the team explained.

“Diagnostic tests included imaging (x-rays, CT scans, MRI), blood tests (CBC, BUN/creatinine, electrolytes) or other tests (cardiac monitor, EKG/ECG, toxicology). Procedures included IV fluids, suturing/staples and nebulizer therapy. Medications included over-the-counter and prescription medications administered or prescribed.”

The criteria also excluded adult patients aged 18 to 64 who were admitted to an inpatient ward, held for observation, or transferred to a different facility, as well as those who left before being seen by a clinician, died in the ED, or were deceased upon arrival.

While the stringent criteria do not truly account for the number of patients who may, realistically, be best served in the primary care or urgent care clinic environment – if an ED physician writes a prescription for a strep throat antibiotic, the visit would not be classified as “avoidable” under these strict guidelines – they do help to illuminate the number of completely unnecessary visits.

Between 2005 and 2011, just over 115,000 out of 424 million ED visits – or 3.3 percent – met the criteria.

Only 22 percent of patients who met the guidelines were Medicaid beneficiaries, and just 28 percent were uninsured. Eight percent had Medicare, and 33 percent were privately insured.

The top five complaints among these patients included toothache, back pain, headaches, sore throats, and symptoms of mental health disorders. When grouped by ICD-9 codes, the most common diagnoses were related to alcohol abuse, dental disorders, and depressive mood disorders.

However, the researchers point out that only a small percentage of the total number of visits from patients with alcohol-related issues, dental issues, and mood-related issues were classified as avoidable, cautioning providers against being dismissive of patients who arrive at the ED with these complaints.

Approximately 90 percent of alcohol-related cases and 83 percent of patients with mood disorders did require some degree of intervention. Only 4.9 percent of dental and jaw disorders were classified as avoidable.

Despite the fact that the majority of patients are in need of care when they arrive at the ED, the typically emergency department is not optimally equipped to treat dental pain, psychological distress, or chronic substance abuse issues, said Hsia and Niedzwiecki.

This leaves emergency physicians with the challenge of treating patients that are not matched with their specific skillsets, which is inefficient on a day-to-day level as well as for organizations as a whole.

Inadequate access to dental services and behavioral healthcare may be partly responsible for this disconnect, the article suggests. Both categories of healthcare have been traditionally viewed as separate from the clinical care continuum, especially by payers.

Patients with sufficient clinical healthcare insurance coverage may not have dental insurance, which is not mandated by the Affordable Care Act.

“For example, of the 46 states in the US that offer dental coverage for non-pregnant adult Medicaid enrollees, 28 provide coverage for preventive services and 18 provide emergency services only,” the study says. “Although providing dental coverage is a step towards increasing access to dental care, less than half of dentists treat any Medicaid-insured patients.”

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, along with provisions in the ACA mandating behavioral and mental healthcare payment parity, helped to expand access to key services during the study period, added the authors, but gaps in coverage and access remain.

Despite the pressing need to ensure that all patients have access to adequate preventive services and ongoing care for substance abuse and mental health conditions, the study concludes by reiterating that the number of patients improperly using the ED for any reason may be much smaller than many estimates profess.

Even the 3.3 percent figure may be an overestimate, “because NHAMCS does not code some minor procedures, our definition conservatively overestimates the number of patients receiving no tests, procedures or medications,” the authors said.

Regardless of its limitations, the data does provide an interesting addition to the discussion around how to define and address unnecessary utilization of services, the authors conclude.

“Our findings serve as a start to addressing gaps in the US healthcare system, rather than penalizing patients for lack of access, and may be a better step to decreasing ‘avoidable’ ED visits.”