elenabs/istock via getty images

What Are the Social Determinants of Population Health?

What are the social determinants of population health, and how can healthcare providers reduce the socioeconomic impacts of community disparities?

Financially and clinically successful population health management programs must take much more into account than what happens to a patient while she is sitting on the exam table.

As the healthcare system’s responsibility expands beyond the clinic walls and into the community, the need to understand and address the social determinants of health has become a top priority.

Helping patients to overcome socioeconomic barriers to better health by spending more on community improvements can reduce downstream medical costs, found the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in a recent study.

States with a higher ratio of social-to-healthcare spending from 2000 to 2009 saw better patient outcomes.

A 20 percent increase in the median social-to-health spending ratio was equivalent to 85,000 fewer adults with obesity and more than 950,000 adults with mental illness, the study added, significantly reducing the associated spending on these conditions and their comorbidities.

But what are the most impactful social determinants of health, how can providers identify areas of opportunity in their communities, and how can they work with their partners to reduce the negative impacts of socioeconomic insecurities?

The World Health Organization defines social determinants as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”

Economic and social policies, political systems, and social norms all contribute to creating the environments in which individuals thrive or experience challenges, WHO says, leaving healthcare providers facing a complex and deeply personalized set of restrictions and opportunities for each patient.

Few healthcare organizations have the resources or political clout to truly eradicate the larger economic, social, and historical constraints that have led to certain groups experiencing long-term disparities and inequities.

But the good news is that population health management programs that address small, manageable pieces of the great American puzzle can successfully change many lives for the better.

Breaking down the social determinants of health into their component parts can help providers assess their community challenges and implement targeted initiatives that improve the health and wellbeing of patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantages.

Safe and secure housing

Housing stability is a key indicator of socioeconomic status, affecting both rural and urban populations. For most individuals, housing is the single greatest monthly expense, says the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity.

Successfully making rent or mortgage payments can be particularly difficult for low income individuals who must spend a larger proportion of their earnings on securing their housing situation.

Unstable housing arrangements can increase emotional, physical, and social stress, present problems with properly storing medications, make it difficult to consistently access healthcare, and lead to gaps or changes in schooling for children that may adversely affect their educational development.

Healthcare providers can also more easily follow up with patients when they have a stable address and contact information, Johns Hopkins adds.

Providers can work to reduce the negative impacts of housing instability and homelessness by partnering with supportive housing programs geared towards preventing loss of housing and providing options for recently evicted or homeless individuals and families.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development offers grants to community organizations looking to create supportive housing to supplement their efforts, while the National Coalition for the Homeless maintains directories of existing supportive housing projects, shelters, and transitional housing initiatives at the local level.

Identifying Care Disparities for Population Health Management

How to Get Started with a Population Health Management Program

English language proficiency and cultural understanding

Most healthcare in the United States is conducted in English, despite the growing cultural diversity that permeates the vast majority of communities. There are currently 41 million native Spanish speakers in the country, in addition to 3.3 million people who speak one or more dialects of Chinese.

Tagalog, Vietnamese, Hindustani, Arabic, and Korean are also spoken by millions, leaving healthcare providers with the task of ensuring that non-native English speakers can understand directions and instructions that are often very complex, even for those fluent in the language.

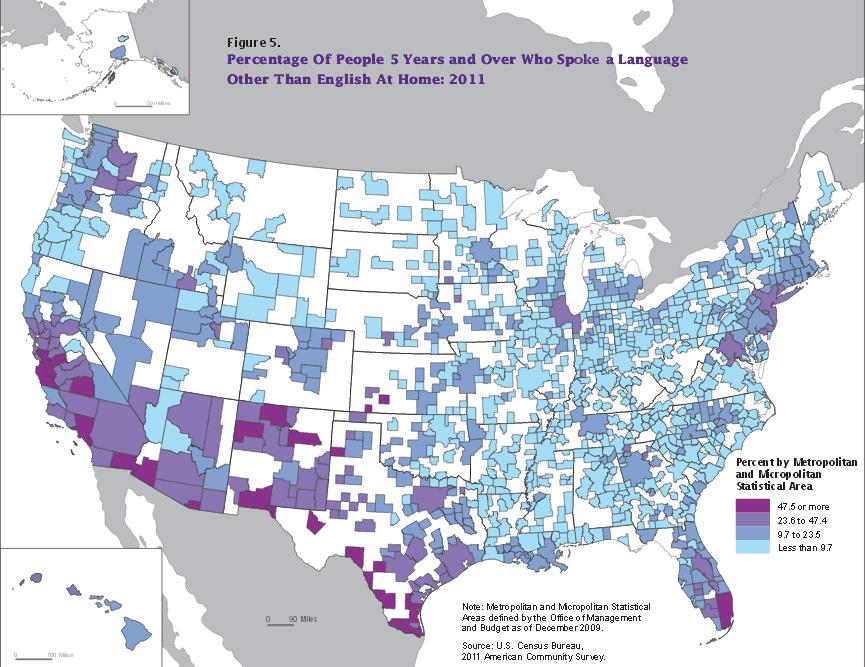

In 2004, more than 46 million people did not speak English as a primary language, and 21 million additional residents were not wholly fluent. By 2014, more than 60.6 million spoke a language other than English at home.

These patients were less likely than others to receive recommended preventive care, more likely to struggle with their medications, and required more visits to the office to meet their needs.

Interpreter services can be costly, especially for uncommon languages. In 2004, the cost was estimated at $279 per person per year. They also may not fully transcend the cultural barriers experienced by non-native English speakers in the healthcare setting.

And family members who act as translators can increase tensions, reduce the feeling of confidentiality, and present legal privacy concerns for providers, says Mayo Clinic dermatologist Michael M. Wolz BMBCH, JD.

The advent of telehealth and mHealth translation services has made it somewhat easier to overcome language barriers. On-demand professionals with proficiency in uncommon languages can reduce the roughly $2 billion spent each year on interpretation services while ensuring access to trained and certified healthcare-savvy translators.

Health literacy and educational level

In addition to ensuring that patients and providers are using the same words, organizations must ensure that those words make sense to individuals with varying levels of health literacy and educational attainment.

Adults with higher levels of education are less likely to engage in risky health behaviors, says AHRQ. And there are dramatic differences in life expectancy strongly correlated with high school and college graduation rates.

By age 25, adults without a high school diploma are expected to die nine years earlier than their graduate peers. Life expectancy among individuals with less than 12 years of education has fallen by more than 3 years for men and 5 years for women between 1990 and 2008.

Educational attainment is correlated with higher incomes, more social resources and stability, improved healthy behaviors, and an improved ability to tackle social and economic stresses. Individuals who secure stable employment are more likely to live in neighborhoods with access to fresh food choices, higher quality schools for their children, and lower rates of violence and crime.

High school graduates are also less likely to be obese, to use tobacco, to be uninsured, to access preventive care and cancer screenings, and to exercise an appropriate amount, the CDC notes.

The “soft skills” learned in school, such as critical thinking, reading comprehension, and social interactions, also contribute to higher levels of health literacy.

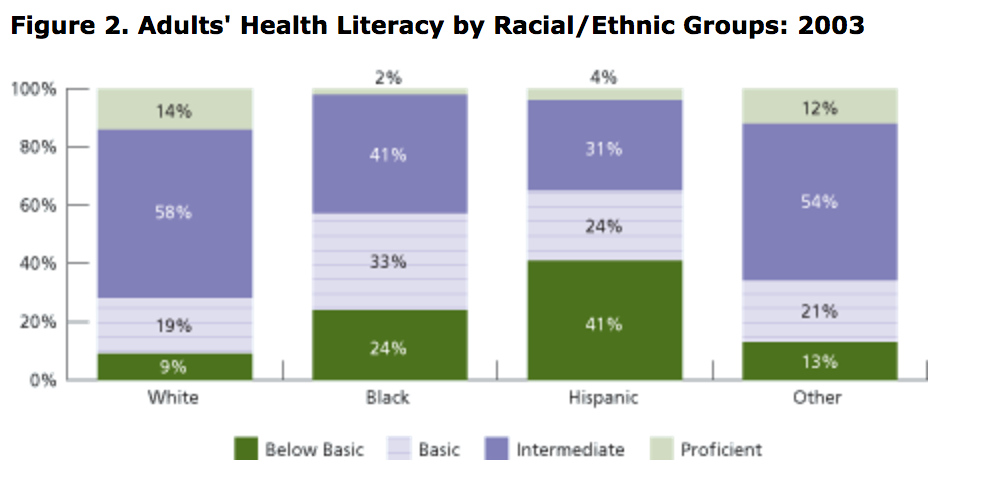

Health literacy allows patients to understand their conditions and the treatments that will improve their overall wellbeing, yet only 12 percent of adults are “proficient” in the art of understanding their health, according to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy.

Providers can help to develop health literacy in patients, no matter what degrees they hold, by training their clinicians in how to communicate clearly and effectively while reducing stress and defensive anxiety in the consult room.

Treating individuals with kindness, patience, and respect while using simple language to explain health issues can help to ensure communication is achieved.

Using Risk Scores, Stratification for Population Health Management

Transportation access

If patients cannot physically get to their appointments or access acute care in times of need, they cannot benefit from even the most robust and effective population health management program.

Missed appointments and no-shows cost the healthcare system billions of dollars each year. One estimate from 2008 says the average cost of no-shows per patient was nearly $200. With a mean no-show rate of close to 20 percent in an average clinic, providers have a significant financial incentive to improve these figures.

Transportation problems are only one small part of the reason why patients might skip out on their scheduled visits, but ensuring access to a lift is one of the easier issues to address.

Medicaid provides non-emergency transportation services to beneficiaries who do not have access to – or cannot utilize – cars, trains, or buses to get to their medical appointments. Beneficiaries who do not hold a driver’s license, don’t have a working vehicle in the household, or have a disability or condition that precludes independent travel are eligible for covered transportation services.

The advent of ridesharing services has also revolutionized the routine healthcare transport environment. In 2016, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that ridesharing apps like Lyft and Uber could significant reduce the $2.7 billion federal spend on non-emergency transportation.

Industry partnerships have proliferated rapidly, allowing patients to access services through their smartphones at lower costs to the healthcare system. As these companies continue to expand into more cities and rural areas, patients may be less likely to miss their scheduled visits.

The CDC also provides a transportation health impact assessment toolkit for providers who wish to understand their community’s challenges and implement strategies to reduce burdens and improve mobility.

Access to healthy, nutritious food choices

Dietary choices are directly linked to the development of costly chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions. Access to healthy, safe, and produce-rich food choices can reduce malnutrition and its associated risk of infectious disease as well as the economic burdens of obesity, which were estimated at $147 billion in 2008.

In 2012, the costs of diabetes totaled $245 billion, including $176 billion in direct healthcare costs and around $69 billion in productivity losses.

Just over half of US residents adhered to recommended dietary guidelines in 2010, while only 20 percent of adults received the recommended amount of daily physical activity each day.

About three-quarters of the population fails to incorporate enough fruits and vegetables in their daily diets, and most exceed the recommended levels of fats, sugars, simple carbohydrates, and sodium.

Educating patients about their dietary habits is an important component of improving eating habits, but so is ensuring that individuals can access affordable healthy foods easily within their communities.

Nearly 30 million people live in areas where the closes grocery store offering produce and other fresh options is more than a mile away. In rural areas, the closest supermarket is often 20 miles away or more. For residents with limited transportation options, this is often too far – especially when convenience stores and fast-food outlets offer closer, cheaper options for a quick meal.

The Healthy Food Access Portal, supported by a collaborative partnership including the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation and Center for Healthy Food Access, can help providers engage in federal and local-level policy initiatives geared at expanding access to quality food choices in low-income and underserved communities.

Why HIE Data Analytics Are Critical for Behavioral Healthcare

Public safety and interpersonal violence

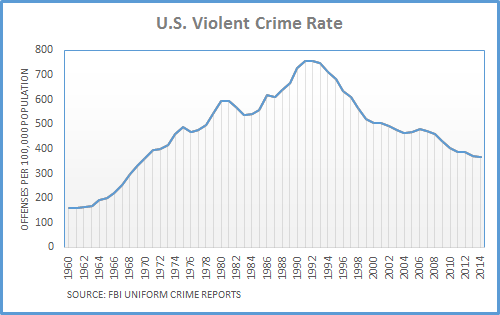

Communities with high levels of crime and violence are also among the most likely to experience widespread economic and social instability. High rates of incarceration, the threat of domestic abuse, child abuse, and interpersonal violence, and prevalent street crime can lead to significant difficulties with maintaining healthy behaviors and accessing care.

Homicide takes more than 16,000 lives each year, and is the leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 24. In 2011, six percent of high school-aged youths said they skipped at least one day of school in a 30-day period due to feeling too unsafe to attend.

Violence can also easily spill over into the healthcare setting, putting clinicians and other staff members at risk. Healthcare organizations spend around $2.7 billion each year on proactive and reactive violence response efforts, the American Hospital Association said in a 2017 report.

The figure includes $280 million for preparedness and prevention, $852 million in uncompensated care for victims of violence, more than $1 billion on training to prevent violence in hospitals, and $429 million coping with care, indemnity, and other costs resulting from violence against hospital employees.

The American Society for Healthcare Risk Management provides a healthcare facility workplace violence assessment toolkit that can help organizations reduce their incidence of violence against staff.

Addressing violence in the community and between individuals requires a concerted, policy-based approach to eliminating opportunities for violence, reducing income inequality that leads to violent tensions, and ensuring that victims of abuse and violence have the resources, support, and skills they need to leave dangerous situations.

Social support and caregiver availability

Loneliness is one of the biggest and most underreported public health threats. While seniors are prone to feeling isolated as their social connections change with age, children and teenagers are also extremely likely to feel as if they are unable to share their emotions and thoughts with friends or family.

The stress of social isolation can lead to premature cognitive decline and dementia, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, exasperation of depression and anxiety, and premature death.

Strong social support networks for children and adolescents contribute to building mental and emotional resiliency that may help to reduce the likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors, succumbing to peer pressure, or developing anxiety-driven behavioral health concerns.

For seniors, caregivers are often involved in making critical health decisions and helping elderly patients cope with hospitalizations and declining independence. About half of elderly patients require significant help with decision-making when hospitalized, said a 2014 study from JAMA.

Nearly 60 percent of the decisions made by caregivers in these situations involved life-sustaining care, while half involved discharge planning and post-acute care.

While the availability of caregivers is crucial for many patients, healthcare providers must also provide support for family members and friends charged with the difficult task of overseeing the needs of their loved ones.

Stress, anxiety, and depression among caregivers are extraordinarily prevalent, with some estimates showing that between 40 and 70 percent of caregivers experience clinically significant mental health concerns. As patients decline in health, the mental health impacts on their caregivers increase dramatically as feelings of frustration, helplessness, loneliness, grief, and guilt can rise.

Ensuring that both patients and their caregivers have the emotional and social support required to make the best possible decisions for themselves and their loved ones can help to reduce the negative impacts of many social determinants of health.

Robust social support networks and community initiatives can prevent malnutrition and improve social interactions among seniors, lower the risk of adolescents engaging in interpersonal violence or leaving school, reduce the risk of chronic disease development due to stress, and make it easier for caregivers to maintain stable employment as well as their own friendships and relationships while they make informed decisions about care.

Successful population health management programs that hope to address the myriad social determinants of health – including the many factors not directly outlined here – will be rooted in providing compassionate, holistic, and personalized support to individuals facing any number of socioeconomic challenges and obstacles in their daily lives.