How to Get Started with a Population Health Management Program

Starting with the basics is the key to developing a successful population health management program.

Healthcare providers are well aware by now that there is no magic solution to the incredibly complex conundrum of systemic reform.

Depending on who you ask, the answer to the puzzle of the Triple Aim is either more technology, less technology, more acquisitions and mergers, increased provider autonomy, less quality reporting, more federal oversight, more incentives for performance, or less of a push towards value-based care.

All across the care continuum, healthcare stakeholders are jostling to make their opinions heard, even as regulatory programs like meaningful use and MACRA continue to exert indisputable influence over the financial and clinical landscapes – and generate plenty of controversy as they do so.

If there is one thing that the entire healthcare system can agree on – a dubious proposition indeed – it is the idea that taking a data-driven approach to proactive, preventative population health management is likely to produce more positive long-term outcomes for patients.

How exactly providers can accomplish that, and whether or not they are appropriately incentivized to do so, are topics that are still up for debate.

But there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that population health management can curb the impact of chronic disease, lower improper utilization of services, improve patient quality of life, and even help providers meet their value-based reimbursement goals.

Given the fact that providers are increasingly acknowledging that they can’t escape the shift to pay-for-performance care, they are starting to turn their attention to developing the strategies and programs that will help them make the switch with the least amount of financial and operational discomfort.

Population health management is at the top of that list, since it sits squarely at the nexus of health IT implementation, big data analytics, value-based reimbursement, improved operational efficiencies, and increased patient engagement.

But how can providers start to engage with this new approach to patient care?

What does “population health management” really mean?

Like many other up-and-coming concepts in the healthcare industry, “population health management” doesn’t have a concrete dictionary definition. David Kindig and Greg Stoddart, who first tried to define the term back in 2003, described it as “the health outcome of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”

Since that time, the healthcare industry has changed dramatically – and so has the notion of population health. While outcomes of patient cohorts are still central to the definition, the rise of big data analytics, and the addition of a performance-based financial component, has broadened the population health management landscape.

In 2016, “population health management” can perhaps be better described as “the process of using big data analytics to define patient cohorts, stratify members by their risk of experiencing certain events, deliver care targeted to the individual needs of those members, and report on individual and group outcomes to ensure quality and accountability.”

Population health management usually begins with gathering key demographic and clinical data about patients attributed to the provider. Attributed patients may be decided by the geography of the service area, their health insurance provider, or their existing diagnoses.

These patients are then sorted into categories based on their clinical history and risk.

Important data for risk stratification may include the number and type of chronic diseases, a history of high utilization or frequent hospitalizations, a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis, advanced age, and an address in a low-income or underserved community.

“The process of using big data analytics to define patient cohorts, stratify members...and report on individual and group outcomes to ensure quality and accountability.”

Using an analytics tool, which can be as simple as Excel or as advanced as a dedicated population health module linked into a local health information exchange, the provider then assigns each patient a risk score.

Patients with higher risk scores may receive extra attention, including more frequent follow-up, social and community support, enhanced care coordination services, medication adherence advice, or an invitation to enroll in an educational patient support program.

Patients with lower risk scores might still benefit from services like automated screening reminders, options to communicate with providers online for minor health concerns instead of scheduling appointments, or small incentives to keep up healthy lifestyle habits.

These strategies and preventative services are intended to help maintain each patient’s highest possible health status while avoiding crisis events, reducing preventable hospitalizations, and improving overall quality of life.

As a result, providers may be able to decrease expensive services, avoid duplication of efforts, raise patient satisfaction, and foster better overall health for their patients.

Using clinical quality measures (CQMs) set by regulatory programs or individual accountable care arrangements, providers report on how often they conduct routine screenings, how well they adhere to industry treatment guidelines for common conditions, and whether or not their efforts are producing results.

High performers may receive value-based financial rewards from payers like Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies, who are themselves saving money on high-end expenses like long-term hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Providers engaging in accountable care contracting may receive a portion of these savings – or be at risk for failing to meet their quality goals. These financial motivations are envisioned to be the most effective lever for driving improvements across the care continuum, fostering a collaborative environment of safe, standardized, high-quality care based on personalized data for individuals.

If performed correctly, population health management can indeed help healthcare organizations meet all three parts of the Triple Aim: improving the patient experience, lowering per capita costs, and raising the overall level of health for large segments of the population.

Is There a True Definition of Population Health Management?

Breaking Down the Basics of Population Health Management

How can providers get started with population health management?

For most organizations founded on the traditional fee-for-service mentality, developing a successful population health management program will require a major change in thinking, starting with the idea that more volume equals more revenue.

Population health management is rooted in the idea that keeping patients away from the office is the ultimate goal, which is why providers may wish to get familiar with some of the up-side shared savings programs available to help get their feet wet with the reimbursement changes that are likely to follow this transformation.

The next step is to start taking stock of the organization itself, and picking a few potential test cases for proving the concept.

Build a strong, multi-faceted population health team

Population health doesn’t just require a new way of thinking, but a new way of executing the daily tasks of patient care. Organizations will have to cultivate innovative skill sets, including care coordination, team-based approaches to distributing workloads, familiarity with data analytics, and a thorough understanding of quality reporting requirements.

A strong team starts at the top, with reliable executive support. Not only does the C-suite have the power to drive change throughout the organization, they also hold the purse strings.

"If [organizations] are going to acquire skilled professionals to drive their business forward, they need to invest.”

Investments in data analytics and population health technologies will have to be approved by the boardroom, and the men and women at the top of the food chain are responsible for forging the business partnerships that will help a coordinated approach to care succeed.

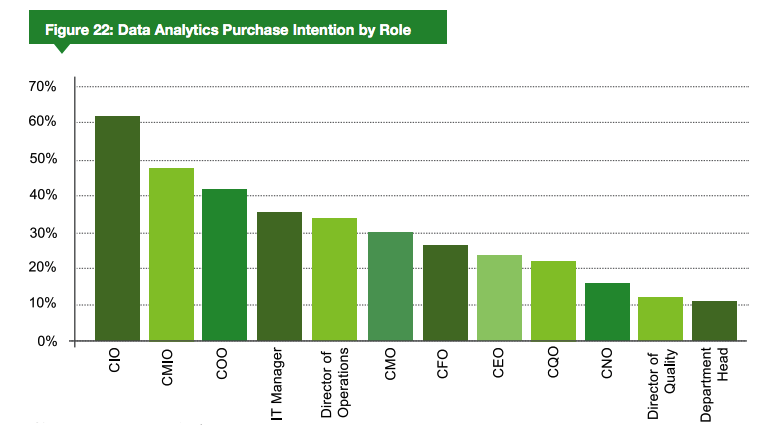

Luckily, many executives are already enthusiastic about implementing population health tools and strategies. A market report from 2015 found that CIOs, CMIOs, and even CFOs are very interested in equipping their organizations with the technology required to manage patients on a broad scale.

Health information managers, informaticists, and data scientists – many of whom are starting to find their way into the C-suite themselves – are also a key component of the population health dream team.

These data governance experts can break down barriers that prevent providers from using EHR data, claims data, demographic and socioeconomic data, and information from other providers for patient care improvements.

“We are the conduit between medicine and the patient, and we make sense of it all,” stated past AHIMA President and Chair Cassi Birnbaum, MS, RHIA, CPHQ, FAHIMA. “We make the systems usable and purposeful, and we have to be able to translate the language of medicine into actionable information. That’s what our contribution to the healthcare industry is: to find out what we’re collecting and why we’re collecting it.”

HIM pros can also optimize existing technologies to meet emerging needs, wrestle quality reporting programs into submission, help improve the quality and integrity of clinical documentation, and even fine-tune workflows that may be affected by big data changes.

Snagging a physician-turned-data scientist or skilled nurse informaticist can also add firepower to the population team.

“The real Holy Grail is a data scientist with a clinical background, of course,” says Sanket Shah, Professor of Informatics at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“If you’re a clinician, or you’ve gone through the right schooling to learn about the medical industry, and you understand patients, you’re going to be in very high demand. There’s so much that the data can’t tell you. You need that inherent knowledge of how it applies to care. That is the ultimate prize as far as hiring is concerned.”

Additionally, organizations are opting to bolster their boots-on-the-ground population health management skills by adding non-physician providers, like nurse practitioners and physician assistants, to handle routine clinical tasks such as answering after-hours hotlines, conducting annual physicals or other screenings, and helping patients make appointments with specialists or behavioral health providers.

“Not every organization understands that if they are going to acquire skilled professionals to drive their business forward, they need to invest,” Shah said. “Either they need to commit to hiring the right people from outside the organization, or they have to train their internal folks, ensure they have a mentor program, and develop the right infrastructure that will support growth.”

Compiling this cross-departmental squadron of patient care and big data experts will prepare organizations for the growing pains involved in the transition to population health.

Building the Team for Big Data Analytics, Population Health

The Role of Healthcare Data Governance in Big Data Analytics

Assess existing technology tools to maximize resources

Some of those growing pains will undoubtedly involve health information technology. While it is theoretically possible to engage analog in population health management, the electronic health record and other digital tools are more or less required for success in the current era.

“It’s very important to be providing the right kind of data in a timely and accurate fashion to physicians and other providers,” stated Mark Wager, President of Heritage Medical Systems. “They don’t just need to understand the patient who comes in the door because they feel so badly today they think they need help. They need data for whole populations of people across a hospital service area and across the population that a payer may contract for.”

The vast majority of hospitals and physician providers already have at least some of the tools in place to make population health a reality.

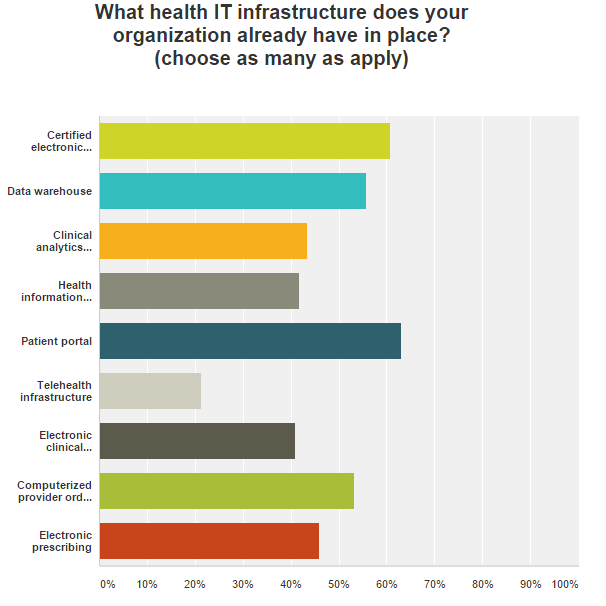

A January reader survey conducted by HealthITAnalytics.com shows that more than half of providers are comfortable with a wide array of health IT tools, including Certified EHR Technology, data warehouses, patient portals, and health information exchange.

Not all EHRs have sophisticated risk stratification features built into their basic design, but it doesn’t take more than a passing familiarity with database technology to start getting a rough view of a patient population.

Simple patient management can start with a name and an ICD-10 code. Just knowing how many patients in an attributed population have diabetes, heart disease, or hypertension can help organizations apportion limited resources, search for new clinical candidates with the right experience, or steer patient education or screenings in the right direction.

“It’s very important to be providing the right kind of data in a timely and accurate fashion to physicians and other providers."

Providers can explore population health modules that can connect with many major EHR brands, or take a crash course in EHR optimization to discover hidden analytics features that may already be available.

The American Medical Association suggests that providers use their existing EHRs to develop a master patient registry and a “health maintenance template,” which can keep track of a patient’s recent immunizations, screenings, and tests. The option to create these record is already available in most EHRs, the AMA says. Maintenance templates can even be programmed to prompt providers to deliver certain services that are missing from the documentation.

For organizations that are ready to take the next steps, the options are nearly limitless. Health IT vendors have been quick to identify population health management as a lucrative opportunity to hawk their wares, and many developers are offering risk stratification and clinical decision support tools driven by cutting-edge natural language processing, semantic computing and data lake technology.

These advanced technologies can finely segment populations for optimal monitoring, conduct predictive analytics, prompt providers to take preemptive action, and make it simpler to exchange information and coordinate care.

What is the Role of Natural Language Processing in Healthcare?

The Difference Between Big Data and Smart Data in Healthcare

Develop a governance plan and strategic roadmap

Once the organization has developed an understanding of the people power and tech tools available, it can decide how to use them, how to augment them, and how to achieve its ultimate goals.

A strategic roadmap that starts with reasonable, bite-size projects that can produce quick results, is an essential component of any population health plan.

“Organizations that do this well have very clear, well-defined care plans,” said Wendy Vincent, Director of Advisory Services at audit and consulting firm KPMG. They know exactly what needs to happen, and they execute those strategies efficiently. They also have contingency plans. That is very important.”

Key questions to ask during this part of the process include the following:

- Are we planning to participate in any formal value-based reimbursement programs, like the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) or a private payer ACO? Are we planning to achieve patient-centered medical home recognition from an accrediting body like the NCQA?

- Do we understand how these arrangements and recognitions will affect our future attestation under the MACRA framework?

- Do have a clear picture of the socioeconomic issues facing our patients? What is the average health literacy level? How will we communicate with them? Do the majority have access to the internet at home, or should we investigate a texting-based platform?

- Do we understand our geographical region and the health resources available to our patients? Can we reach out to the public health department, school districts, and community leadership organizations to better understand the challenges of this particular area?

- Have we thoroughly assessed our baseline data integrity and analytics competencies? Do we understand how our data accuracy, quality, completeness, and timeliness will affect our population health management insights?

- Do we have the skilled staff on board to help meet these data challenges? Are we interested in working with a consultant? Should we consider outsourcing any of our technology or business processes?

- Is there a local health information exchange organization that provides access to population health insights? Is there still a regional extension center nearby that can provide advice on technology adoption and planning?

- What is the first project we will tackle? What is its time frame, its requirements for participation, and its anticipated results? How will we report on its outcomes, and what will we do with that information?

The answers to these questions will determine how deeply an organization can get involved in population health management, and how it can grow its skills and competencies to expand participation in the future.

5 Test Cases to Prove the Value of Population Health Management

Collect feedback on workflows and patient satisfaction

Reporting on quality and performance to external organizations may seem like a chore, but it’s an important part of understanding how to improve. The same can be said for collecting data on internal metrics of success, like provider productivity and patient satisfaction.

EHRs are notorious for sucking hours from the average clinician’s busy day, and adding more population health management tasks to the workflow could make some staff members cringe. The key to ensure that new technologies are meaningful, and that they can solve a specific problem.

“Often times it’s really a process that’s broken,” said Vincent. “An organization will just pick up a technology and try to plug a gap with it rather than ensure that they are doing all they can from a process perspective first. Technology should support the optimal gold standard in workflow, not the other way around.”

Organizations should remember to keep tabs on how well clinicians are adapting to new programs and requirements by taking a hands-on approach to collecting feedback. Understanding how to triage tasks to mid-level providers or where a certain process could be automated with a health IT tool will not only make it easier to adapt, but will also show that the leadership is concerned with the day-to-day business of healthcare.

In addition to that, some studies suggest that when providers are happier with their EHRs, their patients are, too. Clinicians who are comfortable using their laptops are more likely to be able to communicate with patients and form meaningful relationships, while patients who don’t feel ignored by their providers are more likely to feel engaged in their care.

Population health management encourages a collaborative provider-patient relationship and a team-based approach to patient care, which cannot occur if neither party is very happy with the hand they’ve been dealt.

Conducting regular patient satisfaction surveys, and taking the time to understand and address any provider workflow concerns, can help to smooth over the initial rough patches of any major transformational effort.

What are some of the biggest challenges to watch out for?

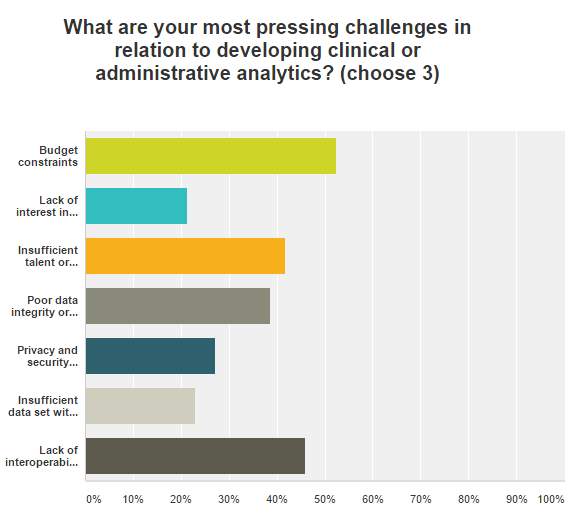

Population health management programs come with plenty of pain points. Financial constraints, a lack of data interoperability, insufficient talent and experience, and low levels of data integrity are among the most significant challenges for many providers.

Accountable care organizations, which have accepted some level of financial responsibility for high performance on quality measures related to population health, have also had significant difficulty with these issues.

Data integration is particularly challenging. While 84 percent of ACOs in a 2016 eHealth Initiative and Premier, Inc. survey have implemented some form of big data analytics software, seventy percent said that collecting data from specialists was extremely difficult, while about half of respondents are unable to send or receive data from long-term care facilities, hospices, and palliative care providers for care coordination purposes.

“The real challenge is successfully moving and integrating that data across dozens of different systems, and we’ve found that out-of-network practices often lack the proper incentives to make investments in the data sharing agreements and interoperable interfaces necessary for success,” said Jennifer Covich Bordenick, CEO of the eHealth Initiative.

EHR vendors are still lagging on the data interoperability front, leaving providers to fend for themselves when it comes to forging the big data connections required to feed their population health management dashboards and data warehouses.

“Today, providers are doing the lion’s share of integration work themselves, making it difficult to establish interoperable connections with those that are not part of the ACO,” explained Mimi Huizinga, MD, vice president and chief medical officer of Premier Inc.’s Population Health Management (PHM) Collaborative.

“Even when those connections exist, that’s really just the first step in a long process of establishing a technical environment to work with the data, create a full view of the care experience and then digest the results across the care team. We urgently need public policies to require interoperability standards in health IT so that providers can access data from any system and unlock the true potential of coordinated, high-quality, cost-effective healthcare.”

And even if providers are able to access the data, it’s not always clear what to do with it. There are dozens of different clinical quality measures paired with a handful of overlapping federal reporting programs, and every private payer may have their own particular definition of what constitutes success for receiving financial incentives.

New reporting requirements like MACRA are set to complicate the landscape even further, especially because the program’s flexibility options open up many different pathways for attestation. CMS has not yet explained exactly how the existing EHR Incentive Programs will give way to MACRA, or when that will happen.

And a series of changes to the popular Medicare Shared Savings Program, along with other new programs from CMS may make it difficult for providers to know which tracks to choose and how they will handle the potential financial impacts of participation.

Despite the uncertainties, it is important to recognize that population health management will be the foundation for the majority of future healthcare reform initiatives. Without a firm grounding in risk stratification, preventative care, and big data analytics, providers will likely find themselves floundering over the next few years of systemic transformation. Preparing now for the organizational changes to come will serve healthcare providers – and their patients – extremely well.