Getty Images/iStockphoto

Combating Chronic Disease through the Social Determinants of Health

Reducing the impact of chronic diseases will require payers and providers to get to the root causes of long-term illness, many of which are attributable to the social determinants of health.

Healthcare providers do their very best to understand everything they need to know about their patients during the few scant minutes they are able to spend with each individual.

Once or twice a year, or maybe when a sore throat strikes, providers collect data on current medications, chat about new problems, and order a prescription or two before sending the individual on his way.

For many patients, these self-contained interactions are perfectly adequate to address low-level concerns or maintain good health.

But for many more, especially those at elevated risk of developing chronic disease, episodic care that begins and ends inside the clinic is simply insufficient to meet their needs.

Chronic disease doesn’t occur in isolation. Conditions such as diabetes, asthma, heart disease, and obesity are all tied very closely to the environments, cultures, and behaviors that surround individuals.

Food insecurity, lack of housing or transportation, low educational attainment, the threat of interpersonal violence, and social isolation create a complex web of challenges that can contribute to deteriorating health, limited functionality, and unnecessarily high spending.

As a whole, these factors are known as the social determinants of health.

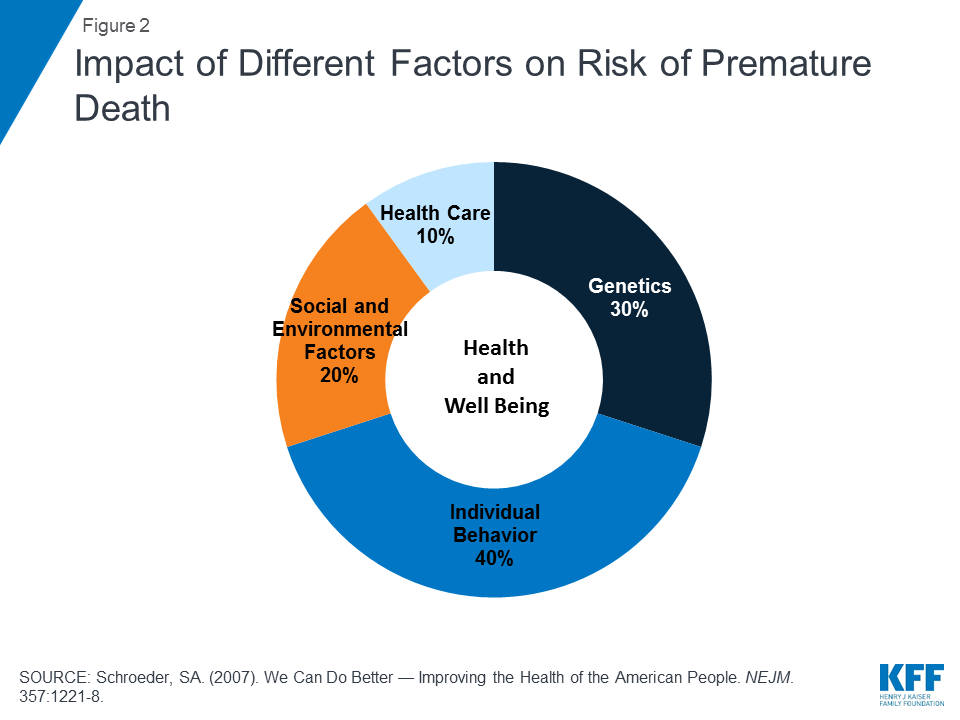

Defined by the World Health Organization as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life,” social determinants may be responsible for up to 90 percent of an individual’s long-term health and outcomes.

Commonly cited statistics pin the impact of purely clinical care at between ten and twenty percent, while physical environments, socioeconomic conditions, behaviors, and genetic predisposition account for the vast majority of factors influencing outcomes.

As a result, healthcare organizations are feeling the pressure to extend their reach beyond the confines of the hospital campus and connect with patients where they live: in their communities, at their work places, in their grocery stores, and at their schools.

From sponsoring community wellness programs to delivering targeted, clinically validated patient education, healthcare providers are increasingly leveraging their leadership positions to help local residents control their chronic diseases and utilize healthcare resources more appropriately.

They are not undertaking these efforts alone. As financial imperatives continue to shift towards rewarding proactive approaches to care, payers are playing their part in trimming costs and reducing the need for expensive acute services.

Both entities are actively seeking out community-based partnerships and closer relationships with public health officials, first responders, non-profits, social work agencies, and other non-clinical organizations.

At the 2018 Value-Based Care Summit hosted by Xtelligent Healthcare Media, panelists and presenters shared insights and experiences about how to make this multi-pronged approach to population health management work for some of the most underserved populations in the country.

By combining the use of data analytics to guide the allocation of scarce resources with some old-fashioned, low-tech approaches to outreach and collaboration, healthcare providers and payers are successfully combatting rising risks in vulnerable communities by addressing the social determinants of health.

Defining the scope and scale of socioeconomic challenges

Every facet of an individual’s life contributes towards his or her ability to successfully manage health.

The luxury of taking paid time off work for doctor’s appointments, affording child care, and hopping in a working car to drive down to the clinic; the ability to understand and act upon instructions from a clinician; the spare cash to pay for a prescription, an MRI, or a follow up – all these factors depend on a person’s personal behaviors, economic status, education, employment, family history, and cultural expectations.

These challenges impact rural populations just as much as inner city communities. In fact, rural patients are more likely to face shortages of physicians, a dearth of high-paying jobs with robust insurance benefits, and difficulties accessing specialty care.

Non-metro communities see higher rates of suicide, heart disease, respiratory disease and stroke – and public health crises like the opioid epidemic are hitting rural areas particularly hard.

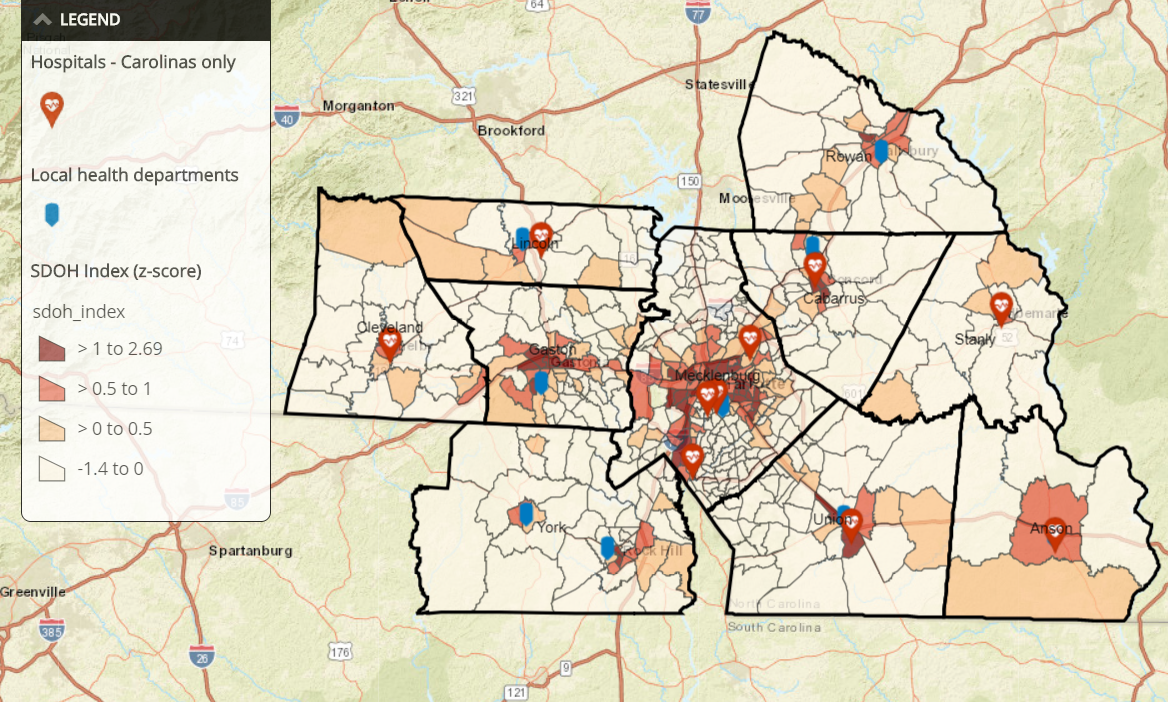

At Atrium Health, a large health system serving patients in North and South Carolina, providers see just as many socioeconomic challenges in rural counties as in the urban areas of the state, said Alisahah Cole, MD, Chief Community Impact Officer.

“When we map social and economic factors like income levels and educational levels, and match that data with the rates of chronic diseases, we can see that every county we serve has at least one dark red area – a pocket of real vulnerability with huge disparities,” she explained, showing a map of Atrium’s service area.

“People in urban Mecklenburg are facing very similar issues to people in rural Cleveland County, so that increases the complexity of the challenges we’re facing, as the healthcare system, to address the social determinants leading to those disparities.”

Healthcare systems are using increasingly sophisticated data analytics strategies to identify the specific challenges in each community, and to monitor the effectiveness of interventions designed to get upstream of unplanned admissions and ED use.

Rising risk individuals, or those on track to become high-spending, complex patients, are a key focus for Atlanta’s Grady Health System, said Leslie Marshburn, Director of Population Health.

“We know that psychosocial needs are going to impact the speed at which someone hits the markers of being a high-risk individual,” she said.

“As a safety net hospital, we're really looking at those individuals who have the chronic illnesses in conjunction with all the social, economic, behavioral, and psychological factors that can contribute to poor health.”

“At Grady, we’re using artificial intelligence to help us build out how we can identify patients in the rising risk, moderate risk, and high risk categories. The challenge is operationalizing that information and using those insights to allow the care team to focus their resources appropriately.”

Hospital readmissions are a popular place to start, she said, due to the potential return on investment for avoiding admissions.

"We know that psychosocial needs are going to impact the speed at which someone hits the markers of being a high-risk individual”

“We look at everyone who is at risk of an avoidable readmission within 90 days,” said Marshburn. “Our tool looks at everyone who has touched our system in the last 12 months or has an upcoming appointment in the next six months – that’s around 160,000 people in any given time period.”

“That might seem like a lot, but it does actually allow our care teams to get a handle on the scope of the problem so they can prioritize and triage their outreach.”

Narrowing the field to target interventions is essential, but it isn’t easy, added John Supra, VP of Solutions and Services at the Care Coordination Institute in South Carolina.

Understanding patterns of utilization and getting ahead of costs is especially difficult in communities where individuals may only access care in a life-threatening emergency.

“We tend to have at least marginally workable data on people who are traditional seekers of care, and that can help with risk stratification and prediction. But what about the people who aren’t in the system?” he asked.

About half of the members of a given population do not seek care in a given year, he explained. Yet at least some percentage will incur high costs in the near future when they experience an exacerbation of chronic disease or another type of acute event.

“Where are these people when they aren’t touching the healthcare system? Are they employed? Do they have contact with faith-based organizations and schools? Are they taking advantage of social services that we don’t know about?”

Marshburn agreed that even the best population health analytics tools can’t be effective without any data to use.

“We struggle a lot at Grady with patients who aren’t represented in traditional data sets, especially in data from payers,” she said.

“They’re uninsured. They live in a cash world, and they don’t engage with the financial system in ways that would create a consumer history. They might have clinical records, but they’re often fragmented. They don’t have regular sources of care that create the patterns we rely on for risk stratification and case management, so we can’t track them in the way that we would like.”

Most healthcare organizations have not yet developed strategies to fill in those blanks and reach the individuals who currently reside outside of the digital environment – they still struggle to identify and care for patients who have electronic health records.

“It’s difficult enough to do any kind of analytics – I know that from experience. But the people in the ether are the ones we need to get to, because the goal of predictive analytics in the context of population health is to understand those people before they end up in the ED or the hospital,” Supra stressed.

“And that will require getting more insight into their communities and finding new connection points to deliver education and preventive care.”

Hospitals, health systems, and physicians are pillars of their communities, and quality healthcare providers tend to enjoy a unique position of trust and influence that can be invaluable for enacting change.

"The people in the ether are the ones we need to get to, because the goal...is to understand those people before they end up in the ED."

In fact, few other entities have such a powerful and wide-ranging impact on the very components of health that may appear outside their direct control.

Healthcare systems must take the lead when it comes to addressing fundamental challenges of vulnerable communities, said Cole.

“We have found that every community needs a convener,” she said. “As a healthcare system, a lot of that burden is going to fall onto us. Atrium gives about $5 million a day in uncompensated care and other community benefits across our region, and plenty of other health systems do comparable work. But we can't do it alone. We can’t solve for all the problems, no matter how much we want to.”

“What we can do is pull everyone together and oversee the development of a cohesive, intentional approach to addressing the social determinants of health. Someone has to be responsible for coordinating those efforts, but we all need to be holding each other accountable to really move the needle on population health.”

Creating a culture of care that begins in the clinic

While advanced risk stratification and data analytics techniques play an important role, many of their suggestions about how to address socioeconomic disparities revolved around fundamental changes that don’t require hiring a team of analysts or signing complicated vendor contracts.

“We talk so much about changing patient behaviors to improve chronic disease management and educating them about how to work within the healthcare system, but we don’t always focus enough on how we, as providers, need to change our attitudes towards our patients,” asserted Caroline Morgan Berchuck, MD, Complex Care Fellow at the Boston University Institute for Health Systems Innovation and Policy.

“Value-based care isn’t just a financial initiative. It requires culture change. Being a good provider is about communication and working with patients on a level that they understand. It’s about relationships, trust, and respect.”

The absence of trust and respect from providers can have long-lasting impacts on how individuals interact – or fail to interact – with the healthcare system, Berchuck continued.

“I actually rotated through Grady during medical school,” she said. “One of my first patients as a medical student was in the A Tower at Grady – there are A, B, C, and D towers.”

The patient, a life-long Atlanta resident who was around 90 years old, told Berchuck that he couldn’t believe he was being treated in the A Tower.

"Value-based care isn’t just a financial initiative. It requires culture change."

“When I asked why not, he said that 60 years ago, the last time he needed the hospital, black people weren’t allowed in the A Tower,” she recalled.

“His experiences at that time had left him so averse to the healthcare system that he barely interacted with it for sixty years. He had miraculously made it to 90 in great health – but it just goes to show how some things that have nothing to do with the clinical care he might have received can really affect personal decision-making.”

Offering a positive, respectful patient experience is vital for success with value-based care, especially when attempting to discuss sensitive SDOH topics such as economic security, education, or interpersonal relationships.

“We need to be more cognizant of those things, and we need to be more thoughtful and compassionate with our patients,” urged Berchuck. “There is so much judgement around diabetes, obesity, health literacy – even the inability to pay for certain services. A lot of that comes from the clinicians themselves.”

“We need to be careful that our patients don’t feel repulsed by their interactions with the healthcare system if we’re going to truly support patients as they make lifestyle changes and navigate their challenging circumstances. That doesn’t cost a thing, but the ROI is huge.”

Extending relationships outside of the traditional confines of the clinic and offering services that meet patients where they are can be a powerful way to make accessing care less daunting or uninviting, agreed Supra.

“The more we can do locally, the better we’ll be at overcoming some of the cultural disconnect between patients and providers,” he said. “We talk about hot spotting and targeting interventions from a data perspective, but we can actually do that from a physical standpoint, too, by bringing mobile clinics into areas that we know are underserved or high-cost and rehabilitating empty storefronts or grocery stores.”

“And when you staff these clinics with people who are culturally competent, speak the same languages, and have ties to the community themselves, you can create connections that are very hard to replicate if you expect everyone to converge on some centralized location away from where they live and work.

“The more we can do locally, the better we’ll be at overcoming some of the cultural disconnect between patients and providers.”

Going the extra mile to create a welcoming, understanding, socioeconomically sensitive patient environment has already paid off for Atrium Health, added Dr. Cole.

After using data analytics to identify patients at high risk of readmission, Atrium looked closer at socioeconomic factors that could contribute to those risks.

“We found that about 70 percent of our high-risk patients were food insecure,” Cole explained. “Of that 70 percent, more than half were eligible for SNAP benefits but didn’t realize that they qualified for assistance.”

In North Carolina, the 13-page application for nutrition assistance is “extremely difficult” to complete, she said. “I consider myself pretty well educated, and even I struggled with it,” she admitted. “Talk about barriers to people achieving good health, right?”

Atrium tasked one of its community health workers with walking applicants through the document to ensure they received the benefits they were eligible for, she explained.

“On average, these people received $200 a month in assistance,” Cole said. “Can you imagine what a help that is to an elderly patient with diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol living on a fixed income?”

Providers at Atrium didn’t have to imagine the results. The impact was clear. The readmission rate for the high-risk patients who received extra help with their applications and subsequently utilized SNAP benefits plummeted by 67 percent.

“That doesn’t just pack a punch financially – although the savings are certainly there. It also positions the community health worker as a valuable resource and an ally, and it makes sure that these individuals know Atrium is there to support them. That’s an attitude shift within the community that goes beyond dollars and cents.”

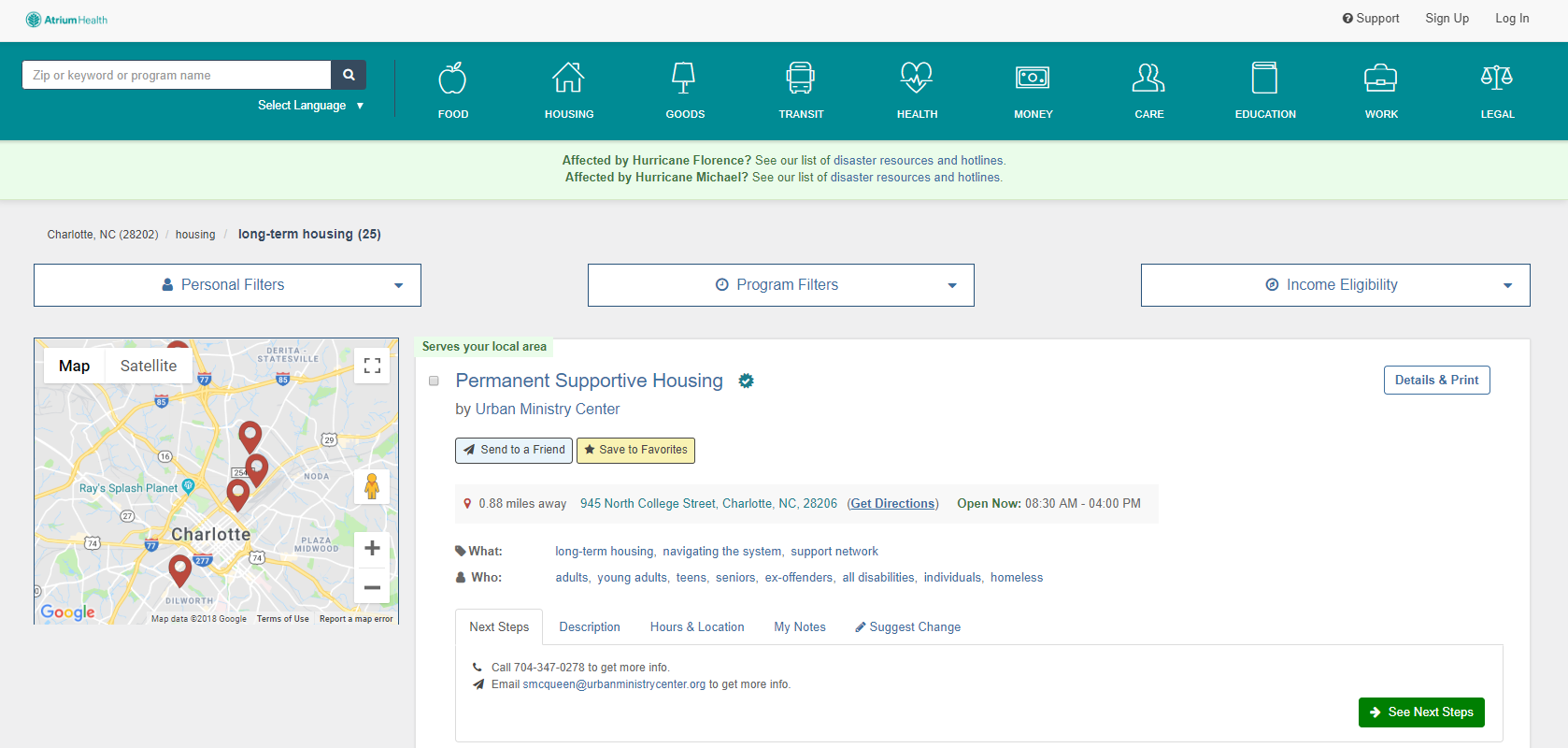

Atrium has also seen success with its Community Resource Hub, an online compendium of community services, such as housing options, legal aid, transportation, and financial assistance for food, utilities, and education.

The website catalogues services nationwide, and is freely available to the public as well as to healthcare providers.

“This is the answer to the question we get very often, which is ‘what do I do next when a patient screens positive for a social need?’” said Cole.

“Now, a community member can self-refer to services, or a member of our care team can do it. And the service agency can talk back to us. It used to be that I never knew what happened after I referred a patient to a community service unless the patient came back and told me that she got what she needed.”

“With the hub, we now have digital communication between these entities that enables us to take action if we need to close that loop.”

Using Health IT to Meet Medicaid Population Health, Socioeconomic Needs

Identifying Care Disparities for Population Health Management

Leveraging payer power to enact change in the community

Payers, too, are offering more options for engagement, education, and access to care.

“Value-based care is encouraging a lot more innovation on the payer side,” said Tina Brown-Stevenson, Senior Vice President of Advanced Network Analytics at UnitedHealthcare.

“One of the studies we did with the United Health Foundation Board was around group prenatal visits. They have proven to be unbelievably popular and successful, especially among low-income women. They really enjoy and value the chance to meet other mothers-to-be, share experiences, and spend some time in an environment that supports them.”

“They have a group session, step out for their individual exams with a nurse practitioner, then come back together and have amazing experiences. That’s a lot more attractive as an incentive to seek care than being told that they need to come to the clinic for an appointment. They get their prenatal care, which is good for everyone, and they get social interacts that they value on top of it. It’s been so successful that we’ve been rolling it out all around the country.”

At Humana, similar community-based initiatives are designed to have net-positive impacts for all parties involved, said Worthe Holt, MD, Vice President in the Office of the CMO at Humana.

“This is the answer to the question we get very often, which is ‘what do I do next when a patient screens positive for a social need?’”

The social determinants of health are a core component of the company’s Bold Goal program, which aims to improve community health by 20 percent by the year 2020.

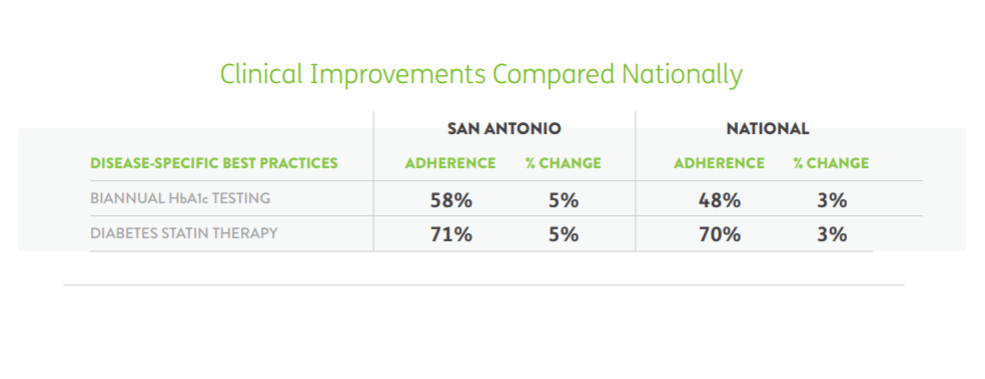

In San Antonio, one of seven original communities serving as anchors for Bold Goal initiative, diabetes is a major concern.

“The dinner table is a central part of the Hispanic culture, where much of the diabetes challenge lies,” Holt explained. “Sharing a meal while recounting the news of the day, telling stories, and spending time with family is very important, but that can make it difficult to make consistently healthy choices about what foods to eat and how to engage in portion control.”

“Until you can help people make better decisions about nutrition and diet without negatively impacting a tradition that is so important to their social lives and family structure, you aren’t going to make a real impact on the development of chronic disease.”

Humana collaborated with grocery stores, the YMCA, and food banks in the San Antonio area to deliver education, ensure food security, and share resources related to managing diabetes effectively.

“So instead of just treating diabetes reactively, we worked with the community to offer more advantageous placement of healthy food alternatives, cooking classes and other education for individuals so they could add some new, lighter meals to their repertoires without feeling like they are making some kind of unsustainable lifestyle change,” said Holt.

By early 2018, the results included a 5.1 percent improvement on the CDC-validated Healthy Days measure for seniors living with diabetes, as well as 5 percent increases in biannual hemoglobin A1C testing and the use of diabetes statin therapies.

While health systems like Grady and Atrium tend to view their coverage areas in terms of entire geographic regions, payers like Humana and UnitedHealthcare are in the slightly different position of being financially responsible for only a portion of individuals in any given community.

Yet Bold Goal projects are open to non-Humana members as well as the company’s health plan beneficiaries, says Holt.

“The Bold Goal and our other work around social determinants is really aligned with the ethos of value-based care,” he said. “We’re going to work with underserved populations, and we’re going to work with people experiencing socioeconomic hardships. It’s going to improve the health of the community – and by the way, it’ll benefit some Humana members, too.”

“Even the tools we’re developing are intended to be payer agnostic. Most physicians work with multiple payers, so it doesn’t make much sense to add to their existing burdens by restricting tools and resources to just our members. If we can produce tools and strategies that can bring value to the entire patient panel, then Humana benefits as much as the physician and all those patients.”

How Rideshare Companies Can Address Social Determinants of Health

Meeting the Challenge of Healthcare Consumerism with Big Data Analytics

Fostering effective collaboration in a changing financial landscape

An open mindset and a non-traditional view of responsibility are vital for creating the transparency and collaboration that will start to make a dent in the nation’s socioeconomic disparities.

As value-based care takes hold across more and more payer-provider relationships, both parties will need to make adjustments to the way they view historical competitive differentiators, such as data assets and the volume of patients served.

"If we can produce tools and strategies that can bring value to the entire patient panel, then Humana benefits as much as the physician and all those patients.”

“Collaboration is truly the name of the game, and that will definitely include collaboration between payers,” said Holt. “For our part, we are working with CMMI and CMS to improve the data assets we can use to make valid inferences and conduct meaningful analytics. We need more than just the population of one payment model from one payer to get a true sense of the patterns and trends that impact health.”

“Aggregated data is essential. We’re talking to other payers at the CMO and CEO level to try to get a group of individuals together who are willing to share de-identified information and create more actionable insights for everyone.”

Payers have a unique level of visibility into those patients who do leave a digital audit trail, but they need clinical data from providers to maximize their analytics capabilities, said Brown-Stevenson from UnitedHealthcare.

“Increasingly, we’re getting data from providers who have electronic health records,” she said. “And we’re working through some of the trust issues that surround data sharing. But a lot of us are still stuck in the fee-for-service mindset, where we have these parameters around who’s staying in our network, who’s using our formulary, and who’s outside of our zone of caring, more or less.”

“Those distinctions aren’t going to help in the value-based care world,” said Brown-Stevenson. “Integration of data will help. Delivering better evidence-based care will help. Data is extremely important to our ability to manage individuals, but we can’t do it all by ourselves. No one can.”

For providers, getting access to the results of those analytics, as well as accessing care coordination data such as admission, discharge, and transfer (ADT) notifications, will significantly boost their ability to be proactive and reduce costs, says Berchuck.

“The integration of the payers with the provider delivery system is really critical,” she said. “In most primary care practices, you don’t have any way of finding out if your patient is in the hospital. The hospital is on a different EHR, or they didn’t call the PCP when they were supposed to – now you’re left with a patient who has had 18 medication changes and a surgery, and you can’t do the follow up that you would do if you knew about it.”

"Data is extremely important to our ability to manage individuals, but we can’t do it all by ourselves. No one can.”

“Payers have such broad visibility into the pharmacy, the hospital, the specialists, and pretty much everything else that is happening to a patient. We need to keep working on integrating that data more effectively into the clinical delivery system.”

Creating alignment between payers and providers will support the ongoing shifting of incentives towards care that takes the social determinants of health into account.

Continuing to reward healthcare providers for approaching healthcare in a person-centered, holistic manner will produce exponential gains in financial and clinical outcomes.

“When the right incentives are in place, we see that people are excited about this and looking forward to engaging,” said Holt.

“We see consumers recognizing that they are getting a more satisfactory experience, and we’re pleased to see that they are pushing for even more change. Employers clearly are, as well. As we demonstrate that value-based care improves quality and reduces expenses across the board, it’s going to have a snowball effect.”

“It’s not going to happen tomorrow, but I am convinced it will happen much more quickly than we might have thought just a few years ago. We’re making excellent progress, and it isn’t going to slow down any time soon.”

The results of investing in communities and addressing social determinants can manifest in a variety of ways, said Dr. Cole, and can truly change lives for the better.

“I'm a kid from one of those dark red areas,” she said. “Statistically, I should not be standing up here on this stage today. There are people like you who invested in me, so never underestimate the power you have as an individual to impact someone's life.”

“If we all committed to work on social health and wellness together, just think about how much more of an impact we can have. We want our communities to be better for us being there. That’s our vision at Atrium Health: that the communities we serve are the first and best choices to live in.”