Getty Images

Identifying Care Disparities for Population Health Management

“If we are going to try to make meaningful impacts on population health management, we really do have to start to look at this.”

Over the last several years, “population health management” has become a key concept for healthcare providers who are trying to recalibrate their traditional operations to meet the growing challenges of value-based reimbursement and accountable care.

The ability to sort patients into clearly-labeled buckets – one for disease state; another for age; a third for known risks – is a foundational step for developing the standardized, comprehensive care frameworks to address the high costs of chronic diseases, reduce preventable readmissions, and connect patients and their caregivers with the resources they need to live healthier lives.

As the health IT ecosystem matures, moving away from the basics of the EHR Incentive Program and towards the integrated, quality-driven world of MACRA, CMS has promised that the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Model (APM) frameworks will help providers develop the technical and practice management competencies they need to meet these new population health management goals.

The upcoming integration of health IT, quality reporting, and value-based reimbursement programs will raise the bar for data interoperability, care coordination, and personalized care – but none of these initiatives can thrive without a clear and thorough understanding of what patients need to access services, maintain adherence, and succeed with self-management.

There is a growing recognition among stakeholders that the clinical care they provide comprises only a fraction of these patient needs.

“Health primarily happens outside the doctor’s office—playing out in the arenas where we live, learn, work and play,” said National Coordinator Karen DeSalvo at the end of 2014. “In fact, a minority of our overall health is the result of the health care we receive.”

Social circumstances, behavioral choices, economic challenges, cultural misunderstandings, geographic barriers, and even the unconscious differences in the way providers treat patients from varying segments of society all have a major impact on outcomes.

Some estimates state that these factors are responsible for eighty to ninety percent of a patient’s results. Clinical care may only impact ten percent an individual’s health, which clearly illustrates the need for providers to generate a better understanding of how to help patients overcome these difficult and deeply-entrenched barriers to better care.

Unfortunately, the healthcare system’s patchy and fragmented progress towards developing an integrated care continuum has left providers, rule makers, and other stakeholders without the data they need to discover exactly why these disparities occur, where they occur, and how detrimental they are – let alone how to prevent them.

The data that is available reveals a sorry state of affairs when it comes to equal care access and equal results. Again and again, certain socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups incur more spending, utilize more services, live with higher burdens of chronic disease, and experience drastically different outcomes than their peers.

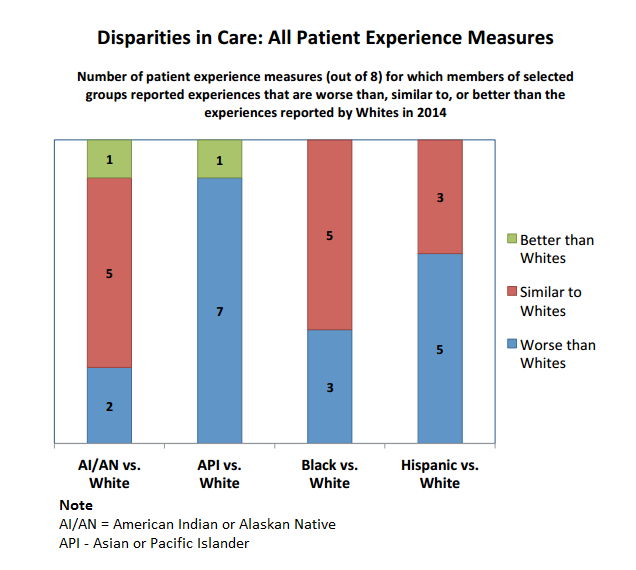

In 2014, CMS found shocking differences in the way minority populations experience patient care when compared to white patients.

Asians and Pacific Islanders reported worse experiences than white patients on seven out of eight quality metrics, which include access to care, customer service, and provider communication skills.

Hispanic patients stated that their experiences were worse than whites in five domains, while black patients fared worse on three out of the eight domains.

Why are there such significant differences in the way ethnic and racial groups interact with the healthcare system, and how can providers address and ameliorate the underlying causes of these disparities?

With the help of the Director of the CMS Office of Minority Health, Cara V. James, PhD, HealthITAnalytics.com takes a deep dive into the data in an effort to better understand the obstacles faced by patients and their providers when it comes to implementing truly effective population health management strategies.

The problem of defining the problems

“Part of the challenge is that we don’t always have data on race and ethnicity for some of our beneficiaries. It’s a voluntary reporting field, of course, so there are often gaps in that data,” said James, who also works with the Institute of Medicine to promote health equity and reduce disparities.

“We aren’t able to report for all the populations because of the small size of the data for some of those groups,” she continued. “It’s the best we’re able to do at this time, but it does produce an incomplete picture. That being said, there is still so much we can learn from the information available.”

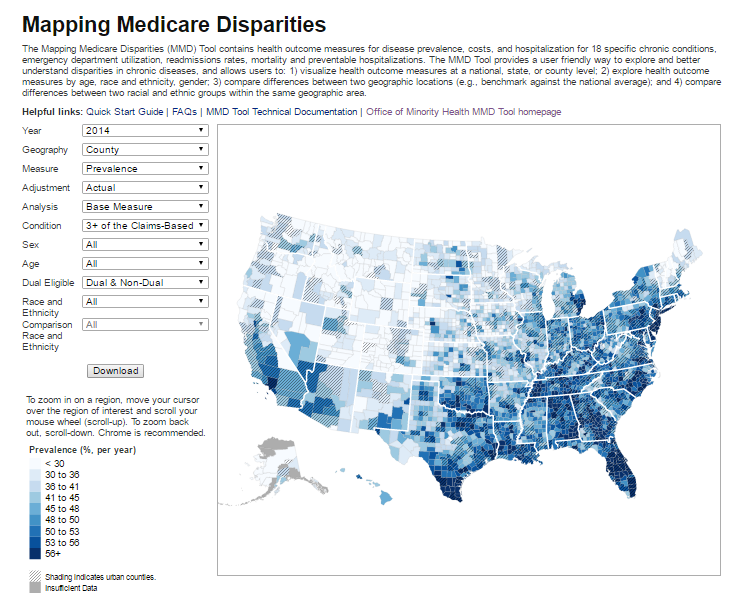

The Office of Minority Health has contributed hugely to that pool of available information by releasing the Mapping Medicare Disparities (MMD) tool, a public dataset with an interactive, online interface that allows users to conduct their own tailored population health management analytics.

Data is available at the county level for measures including hospital readmissions, mortality rates, and emergency department use, not to mention the prevalence and costs of diseases like diabetes, heart failure, COPD, and chronic kidney disease.

Users can view dynamic maps with data from 2012 to 2014, and choose to view measures based on race or ethnicity, dual eligibility, age, or sex, and even generate findings based on which patients have a combination of two or more chronic diseases.

The data allows providers to get an inside look at the immensely complicated landscape of chronic diseases and service utilization, and they will see a landscape that throws up obstacles at every turn.

Not only is it difficult to collect comprehensive data on racial and ethnic distributions, but few providers are systematically gathering social and economic data that would help CMS and others develop stronger links between patient outcomes and social determinates of health such as housing problems, lack of transportation, or food insecurity.

“We know those are important, and that looking at those issues is a really critical piece of trying to improve,” James said.

“When you look at the mortality indicators or the prevalence rates for heart disease and diabetes, those are related to so many circumstances that occur outside of the traditional healthcare system.”

CMS innovation projects, like the new Accountable Health Communities Model, are hoping to expand the collection of data related to social determinates of health, which will greatly help the effort to understand gaps in care and connect patients with the community services they need to overcome deeply entrenched barriers to better health.

The model will require providers to screen their beneficiaries for unmet health-related social needs and leverage strong community partnerships to connect patients with appropriate services.

The five-year program will encourage participants to increase patient awareness of service options, help patients navigate an often-complicated public health system, and align clinical care with socioeconomic aid to ensure that patients extract maximum benefit from complementary services.

“We want local providers to understand the issues facing their service areas, and we want to give them the opportunity to drill down into some of the factors related to their work that may need improvement,” said James.

“As we continue to link socioeconomic factors to clinical care, we will be able to rethink how to address these relationships, and I believe that will help us make a meaningful impact on metrics like readmission rates or medication adherence.”

With millions of dollars in funding currently available for 44 pilot sites, the program will help providers make a concerted effort to address housing instability, interpersonal violence, food instability, and transportation needs to ensure that patients have the ability to take ownership of their health.

Pulling back the veil on health disparities

The MMD tool may not include everything providers need to know about solving the problems of population health, but it can certainly help stakeholders frame the right questions.

Why, for example, are the states with the lowest levels of certain chronic diseases spending the most per patient on care? And why do those costs differ so drastically between racial and ethnic groups?

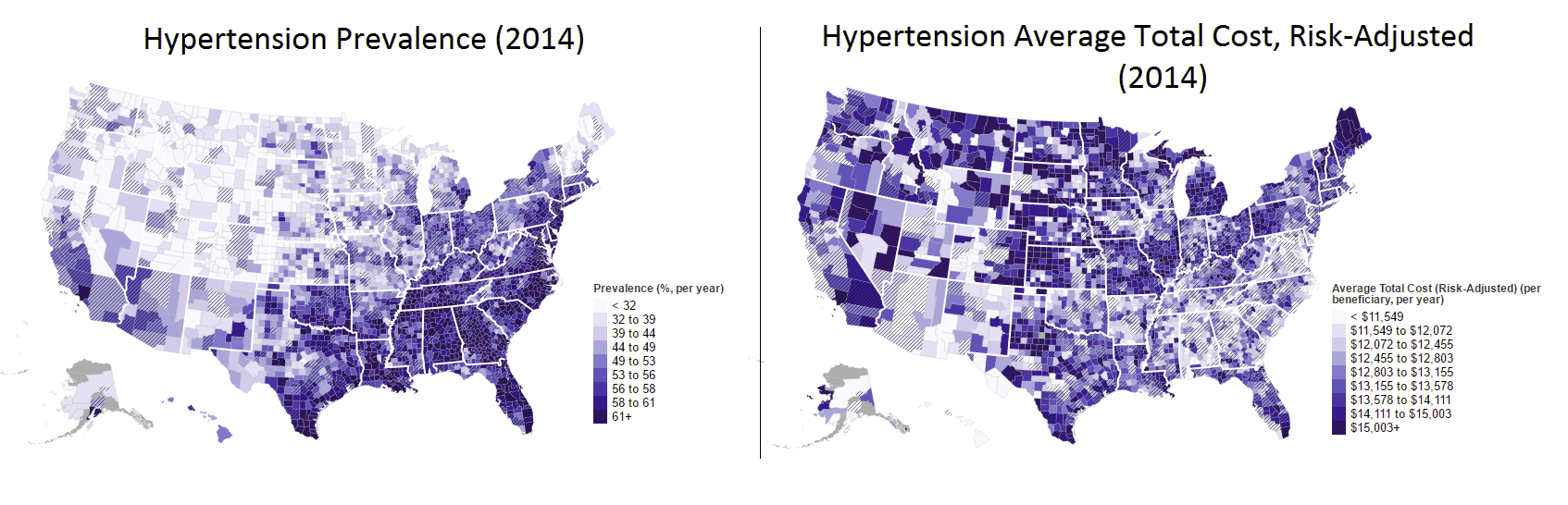

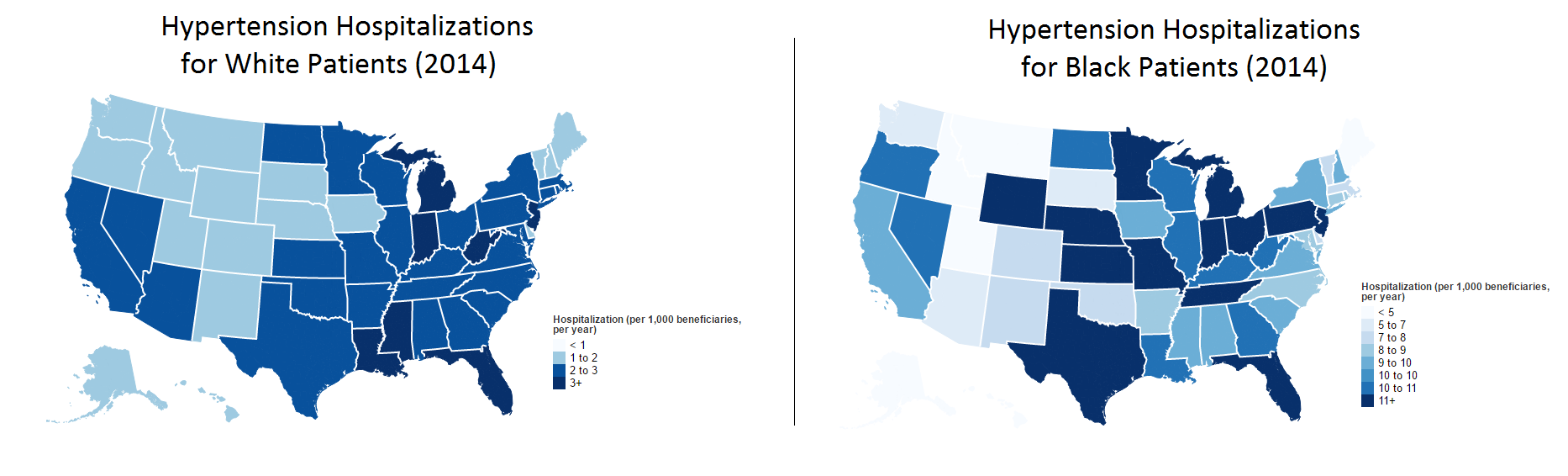

The trends are surprisingly clear for several of the chronic diseases included in the data, such as hypertension and diabetes, two of the most common conditions for Medicare patients.

While many patients in the Deep South are twice as likely as people in the Midwest or Pacific Northwest to have hypertension, patients in Montana, Nevada, Washington, the Dakotas, and Idaho are incurring significantly higher per-beneficiary costs than those in Georgia, Mississippi, or Alabama.

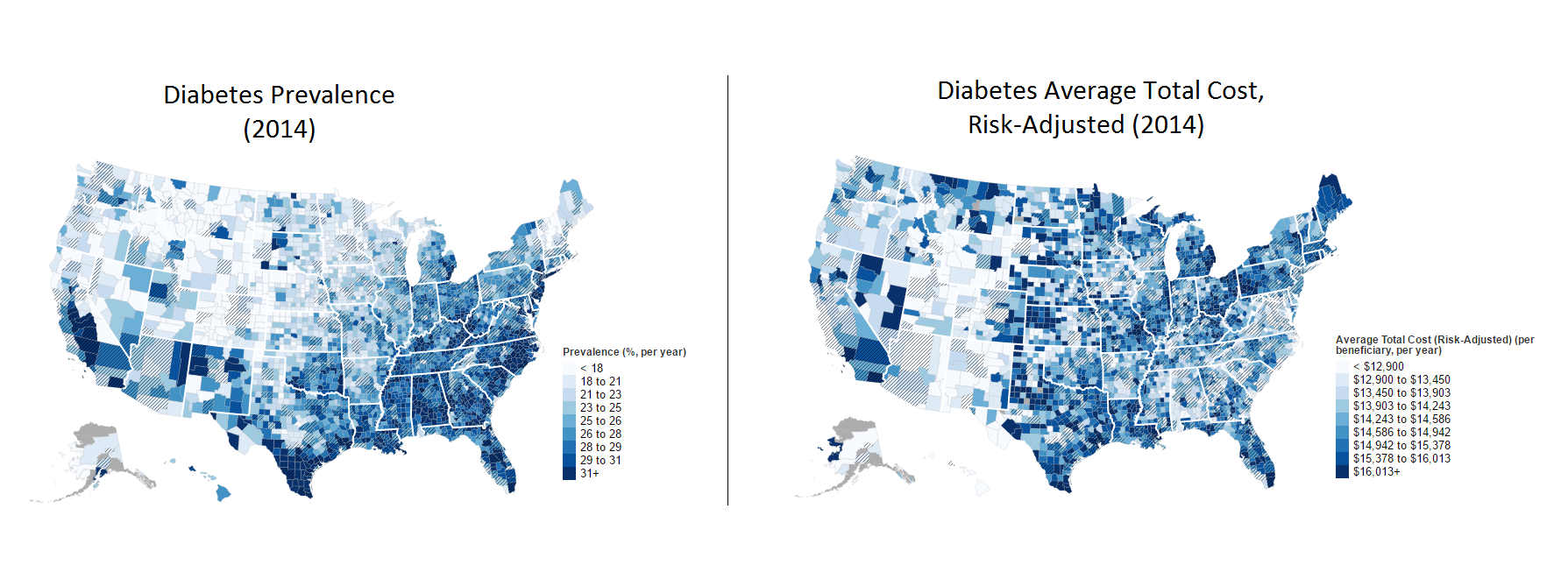

The patterns for diabetes spending are similar. Again, the Deep South fares poorly when it comes to prevalence, but states like Maine, Michigan, and Montana are pouring significantly more money into diabetes management.

There are several possible explanations for this data. States with a higher prevalence of common chronic diseases could simply more familiar and experienced with what it takes to manage patients with these conditions, and could have developed more cost-effective treatment strategies that they have implemented successfully.

Or maybe patients in the Southern states are less likely to seek care for their diabetes and hypertension than patients elsewhere, which would skew the data into showing lower costs. Perhaps patients engage in an initial consult, but do not come back for follow-up care.

High unemployment and poverty rates, lack of insurance, poor transportation infrastructure, and lower levels of patient education may all contribute to this circumstance – but since these data points are scarce, it is difficult to say how these factors impact spending and outcomes.

The questions pile up further when racial and ethnic data is added to the equation.

When it comes to diabetes care in Texas, for example, it costs $14,819 to treat a patient identifying as non-Hispanic white, $15,529 for a Hispanic person, and $17,624 for a patient identifying as black.

For hypertension, the disparities in care are even more pronounced. For every 1000 white patients in Texas, there are between two and three hospitalizations per year for hypertension-related causes. Five out of every 1000 Hispanic patients will experience a hypertension hospitalization.

For black patients? More than 11 out of every 1000. The disparity is so markedly pronounced that the map key even uses a vastly different scale to illustrate the data.

While black Americans nationwide are about ten percent more likely than non-Hispanic whites to experience hypertension, that does not explain why they are five times as likely to end up in the hospital.

Worryingly large variations in the provision of preventative care, routine screenings, and mental healthcare may have something to do with it.

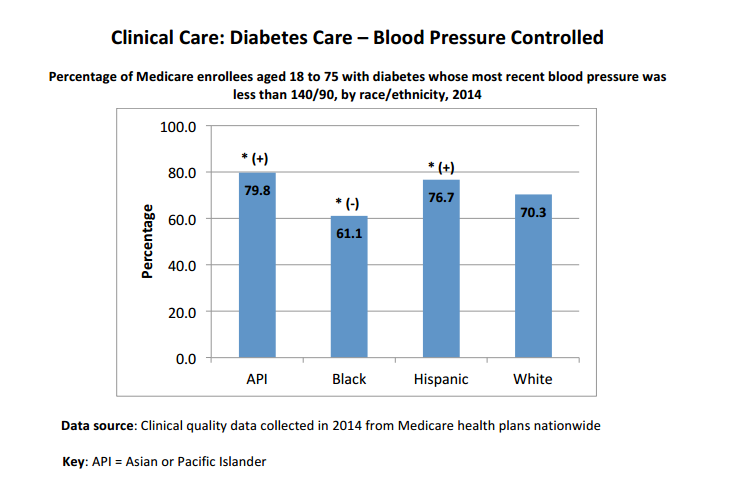

Additional CMS data on racial and ethnic disparities shows that black patients with diabetes are nearly ten percent less likely than white diabetics to have their blood pressure under control, and eight percent less likely to have a blood sugar level within acceptable range.

Black Americans with cardiovascular conditions are the least likely to receive cholesterol management services, as well. While 75.7 percent of Asian or Pacific Islanders with recognized cardiovascular problems had their cholesterol levels addressed appropriately, just 51.9 percent of black Medicare patients could say the same.

Black and Hispanic patients are also significantly less likely to receive antidepressant treatment after a new depression diagnosis, rarely receive follow-up care within seven days of a discharge from a hospital for a mental health condition, and are unlikely to remain on medication to treat depression for more than six months.

Developing understanding before enacting change

CMS and other federal authorities are well aware of these shocking statistics, and are making an effort to ensure that the health system’s increased focus on population health management includes techniques that will help to close these massive racial and ethnic gaps.

The CMS Equity Plan for Improving Quality in Medicare, released last fall, focuses on breaking down barriers that prevent underserved and disadvantaged populations from accessing high quality, comprehensive care.

Gathering good data is still the first task, noted James. “The collection of standardized data, and the reporting and analysis of that data, is a top priority for the CMS Equity Plan,” she said.

“That focus was born out of the listening sessions we held across the country as we formulated the plan. Hands down, the most important thing stakeholders told us was that we needed a better understanding of the challenges we were facing before we could enact change.”

Along with improving data collection and dissemination, the Equity plan includes five additional action points to help Medicare providers deliver quality care to all their patients:

• Evaluate the impact of health disparities and integrate equity solutions across CMS programs

• Develop and disseminate strategies that are likely to reduce disparities and variations in care

• Increase the ability of healthcare providers to meet the needs of vulnerable or underserved populations

• Improve patient-provider communication for patients with disabilities or limited English language proficiency

• Ensure that health care facilities are physically accessible to patients and caregivers

These guiding principles will help CMS and the healthcare system at large address some of the most challenging situations, including reducing readmissions for patients with multiple chronic diseases, ensuring that long-term care facilities provide culturally competent services to vulnerable seniors, and improving post-discharge care coordination for minorities and people with disabilities who also experience mental illnesses.

Encouraging healthcare providers to take action

The healthcare industry will need more than a CMS roadmap to make measurable progress on reducing health disparities, however. Provider organizations, especially at the primary care level, will need to commit to closing the gulf between different patient groups.

Transforming the primary care setting into an accessible hub for patient management may be an important first step, says James. “The idea of a medical home as a place where patients can go to get most of the care they need is very important,” she said.

“The medical home can produce coordination of care – and in the Accountable Health Communities program, that includes fostering connections to social services,” she said. “As more organizations take on this approach, they will start to realize the important role that social services can play to help drive better outcomes. That’s where we’re headed as a system, and figuring out how to do that intelligently is a high priority.”

The NCQA Patient-Centered Medical Home model, which has enjoyed great success among provider groups that manage to hit upon the magic recipe of technology and practice innovation, also stresses the importance of connecting with community resources to support patients outside of the clinical walls.

The framework requires providers to sit down with patients and their caregivers to document their vulnerabilities, competencies, and challenges before charting out a specific plan to overcome these obstacles. PCMH providers must also engage in specific follow-up activities, including checking in with patients after a referral, when test results are available, or after they transition between care settings.

The PCMH guidelines also stress the delivery of culturally and linguistically appropriate services and resources, such as distributing educational materials about medication adherence in the patient’s native language.

“We want to make sure we are providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services for patients,” James said. “We want to be sure that we are interacting in the best possible way with each patient in front of us so that providers can really address their challenges. That is the only way we will achieve the results we need.”

Providers will be further incentivized to adopt patient-centered care strategies as MACRA comes into play. Organizations that engage in Advanced Alternative Payment Models, which include a medical home requirement, may be eligible for a five percent bonus on their Medicare Part B reimbursements, and will receive more generous annual increases in their payments than other providers.

Next Generation Accountable Care Organizations, advanced Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and participants in the new Comprehensive Primary Care Plus program will all have a chance to qualify for these financial perks.

Providers who opt to participate in MIPS instead will still be contributing to the cause. The quality reporting requirements that form the basis for this program will help to add to the industry’s understanding of how to close gaps in care.

Embracing community cooperation for a better future

If the first step to recovery is admitting that there is a problem, it’s time for the healthcare industry to come clean. There are gaping cracks in the care delivery system, and they run along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines.

“If we are going to try and really make meaningful impacts on population health management, we really do have to start to look at this,” James urged.

Providers may not even be aware of the fact that some patients’ experiences differ so drastically from others, but they can no longer afford to avoid the issue by operating in isolation. Small efforts, such as connecting with a community shuttle program, creating a call-sheet of the public health organizations in the area, or making a nursing hotline available for after-hours advice, can radically change the way patients interact with the healthcare system.

In order to produce measurable improvements in the way patients access, experience, and benefit from care, organizations must coordinate and cooperate with their community service organizations to help their patients achieve better health, better outcomes, and better lives.