Getty Images/iStockphoto

Improve Coverage, Health Equity By Diversifying Broker Recruitment

Access to care can vary based on access to health insurance brokers, so when broker pools lack diversity health equity suffers.

When Access Health CT (AHCT), Connecticut’s marketplace, published its health equity report, leaders of the state health insurance marketplace knew that something needed to change.

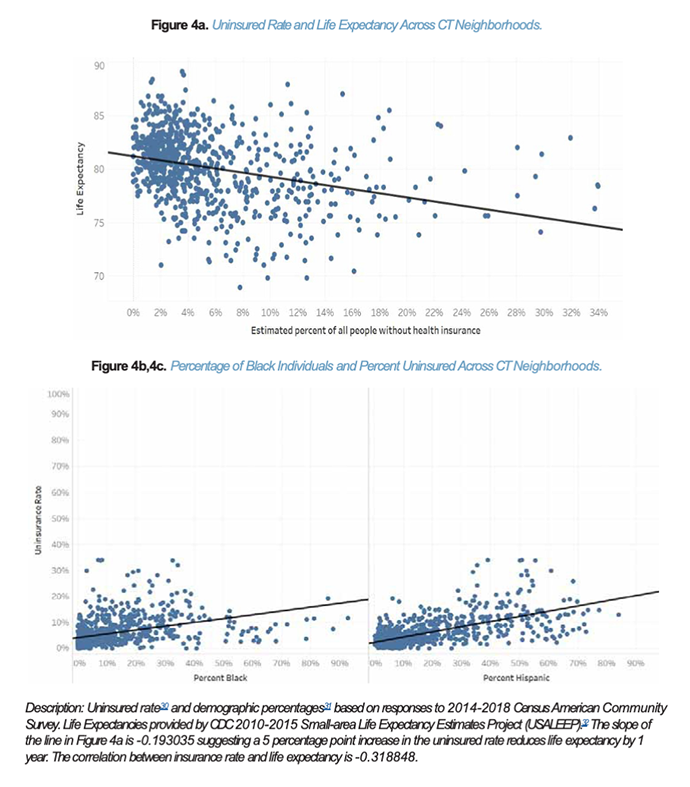

In a state that ranks among the healthiest and wealthiest in the nation, the report revealed striking disparities. The state boasted high life expectancy overall (80.9 years), but life expectancy among Black and Hispanic residents was more than a decade lower than the average (68.9 years). Additionally, Black Connecticuters had the highest mortality rate in six out of the top ten leading causes of death.

Apart from differences in clinical outcomes and barriers, one set of statistics stood out to James Michel, chief executive officer of AHCT: coverage disparities.

The state has an uninsurance rate of 5.9 percent, which is better than the national average. But the uninsured population is disproportionately composed of the state’s Hispanic and Black residents. As Michel and his team looked more closely at the uninsured urban communities, they found a common barrier to health insurance.

“We noticed that there are almost no brokers in those communities of color,” Michel told HealthPayerIntelligence. “In Connecticut, to advise anyone on purchasing health insurance, you have to be a licensed broker, [so] that's a big hurdle for those communities.”

Various systemic issues made finding a broker difficult for people of color. In Connecticut, the broker community largely consists of white men in their 50s, Michel explained. Many firms are family-owned small businesses, leading to inherited knowledge that accumulates with each generation.

In contrast, people of color have lower exposure to the broker industry. And the lack of diversity in the broker industry meant that even for minority individuals who did manage to access a broker, cultural and trust barriers could prevent the customer from fully utilizing the broker’s services.

Michel and AHCT’s Health Equity and Outreach department, headed by Tammy Hendricks, responded to the report by launching the Broker Academy, a course that supported applicants from underrepresented communities through the broker licensing process.

While establishing this program, the AHCT team developed strategies around diversifying the broker community to expand access to care.

AHCT’s broker licensing support program

AHCT’s first step was to recruit applicants from the targeted populations. The recruitment teams focused on areas with the highest concentrations of non-white residents, some of the highest uninsurance rates in the state, and the lowest access to brokers.

To the team’s surprise, 70 percent of the first class consisted of working-class women, most of whom were women of color and anywhere from 20 to 60 years old. Considering the demographic trends in the industry, these results represented a strong start to achieving the program’s goal.

After the department finished recruitment, the course began. The Broker Academy’s first classes launched on June 1, 2022 with 71 students. The program revolved around the pillars of the state’s licensing process—training, pre-exam, licensing exam, and license application—but interwove these steps with additional resources and requirements.

Before the week-long training, AHCT hosted two to three months of classes. Guest speakers visited the classes to share their experiences as brokers, including their personal perspectives on the licensing process.

For many applicants, it had been decades since they sat in a classroom or took a test. Thus, a core element of the program involved empowering applicants to conquer that fear.

When the classes finished, the participants entered a three-day, state-certified training. After the training, the applicants did the pre-exam, exam, and licensing applications. Lastly, AHCT connected program newly licensed brokers with experienced broker mentors.

All 71 students participated in the recruitment, classes, training, and pre-exam. At the end of the course, 29 students sat for the exam, and all of them passed. These students are now licensed brokers for the state of Connecticut.

Key components of a successful broker diversification program

Michel outlined five major components of a successful broker diversification program for states looking to improve their broker pools.

First, Michel emphasized the recruitment process. Any qualifying individual could apply, but AHCT implemented a rigorous procedure to ensure accepted applicants would make it through the program.

Applicants submitted up to three community leader reference letters, a personal statement, a resume, and their high school diploma or general education (GED) credentials. They also had to demonstrate community involvement and customer service skills. Finally, the applicants engaged in an hour-long interview with three AHCT employees.

Effective recruitment is important for AHCT and applicants alike. It allows the organization to assess which applicants will most likely finish the Broker Academy program. But it also enables prospective students to learn more about the process and the broker profession.

Second, AHCT removed financial barriers to entry that potential broker applicants might experience.

The Connecticut insurance license process can cost around $375 or more. If applicants fail and want to retake the exam, each retest costs $79. On top of those expenses, applicants must secure access to a laptop.

The Broker Academy program fully covered applicant fees, including the costs of two exams. The program also offered every applicant reconditioned laptops that the IT department refurbished.

We noticed that there are almost no brokers in those communities of color.... In Connecticut, to advise anyone on purchasing health insurance, you have to be a licensed broker, [so] that's a big hurdle for those communities.

Third, programs should educate underserved communities about what a broker is, how to begin that career path, and the important role brokers play in a community.

As trusted individuals with a shared history or culture, brokers who are members of underserved communities can upset patterns that lead to low coverage rates, foregone care, and poor health trends. When applicants understand this potential for impact, it can override their fears around the process.

Fourth, Michel emphasized his staff’s enthusiasm and collaboration around this initiative as pivotal to its success. Team members committed time outside of their normal job hours to support the training process. For example, when the IT department refurbished laptops for the 71 applicants, they did so over the weekend before the first day of the course.

“I was so proud of our organization because they were so happy to jump in. And they were doing this in addition to their regular job,” Michel said.

“They were just very happy to be part of something, to help to make a difference in the lives of the people that they were helping, also the communities that these people were a part of.”

The endeavor involved other departments at AHCT in addition to the Health Equity and Outreach department. The HR department assisted with recruitment. The IT department offered technical support. The training department helped design the pre-training.

In addition to the internal team’s work, the program attracted support from external entities. The governor’s office sent out a press release when the Academy launched, encouraging residents of targeted communities to apply.

“For this to be successful, you have to have complete organizational support behind it. The entire board of directors and the governor's office were extraordinarily supportive because they saw the value. It was a new, creative, novel way of helping to address health disparities, and it gives people an opportunity to make a decent living,” Michel said.

Finally, it was key to support students as they overcame their fears around education, the training process, and examination.

All of the students who sat for the exam passed and were licensed. However, slightly more than 40 students did not take the final exam.

“They worked hard. They were studying together after class, during class, so they were empowered for the pre-exam. They all passed it. Every single one of them passed it. But only 29 of them took the exam,” Michel said.

“When we reached out to [applicants who did not take the exam], they were just intimidated about taking the exam, and they were afraid of failing. So, one of the challenges we have is: how do we get them over that hump? And in year two, that's a big part of what we're doing now.”

Future changes to AHCT’s program

When the team gathered offsite in December 2022 to debrief about the program, they documented a number of the changes that they made, either during the process or would have made in hindsight, to incorporate these findings into the program’s second year.

AHCT aimed to expand its applicant pool to 100 new applicants when year two kicked off in June 2023. Additionally, while the program’s first year targeted applicants in urban centers, the team decided to extend this opportunity to rural residents in the second year. Data showed that working-class white populations in rural Connecticut also experienced barriers in access to coverage.

Michel emphasized that AHCT would tighten up the recruitment process to ensure that more participants would sit the exam. The organization planned to leverage its HR platform to streamline the application process for Broker Academy. Previously, applicants had to apply by email.

The team also planned to expand the program from three to five days, hoping to make students more comfortable with the materials. Additionally, the students would receive new laptops, not refurbished devices.

These changes meant AHCT would spend more on the program in year two, but Michel said the impact was worth the cost.

“Broker Academy, we believe, would be one of the more creative ways to help address health disparities, in that [participants] become a resource for their communities,” Michel said.