How Payers Help Tackle Substance Use Disorders, Other Conditions

Payers have several opportunities to improve their coverage options for members who have substance use disorders with co-occurring conditions.

The National Quality Forum’s (NQF) Opioids and Behavioral Health committee brought together healthcare leaders from across the nation to explore an under-represented subject: strategies around substance use disorders with co-occurring conditions. In September 2021, NQF compiled a 35-page report of the committee’s recommendations.

Given the dual dimensions of their conditions, members with substance use disorders and co-occurring or “concurrent” conditions require nuanced care strategies. Their treatment must be holistic in order to be effective. But payers — and the healthcare system as a whole — have struggled to fully address these members’ needs.

To some extent, the report’s findings encouraged Caroline Carney, MD, chief medical officer at Magellan Health and one of the committee members.

“I’ve been doing internal medicine/psychiatry combined the whole of my clinical career. I’m incredibly encouraged to see the country coming into the recognition that holistic care is where we have to head,” Carney told HealthPayerIntelligence.

However, the healthcare system still has a long way to go before it is well-adjusted to the needs of members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions, Carney and NQF noted.

Status of coverage for co-occurring mental health, substance abuse care

Members who have substance use disorders with co-occurring conditions may face several barriers that payers can address, the NQF paper identified.

First, members may experience coverage disruptions.

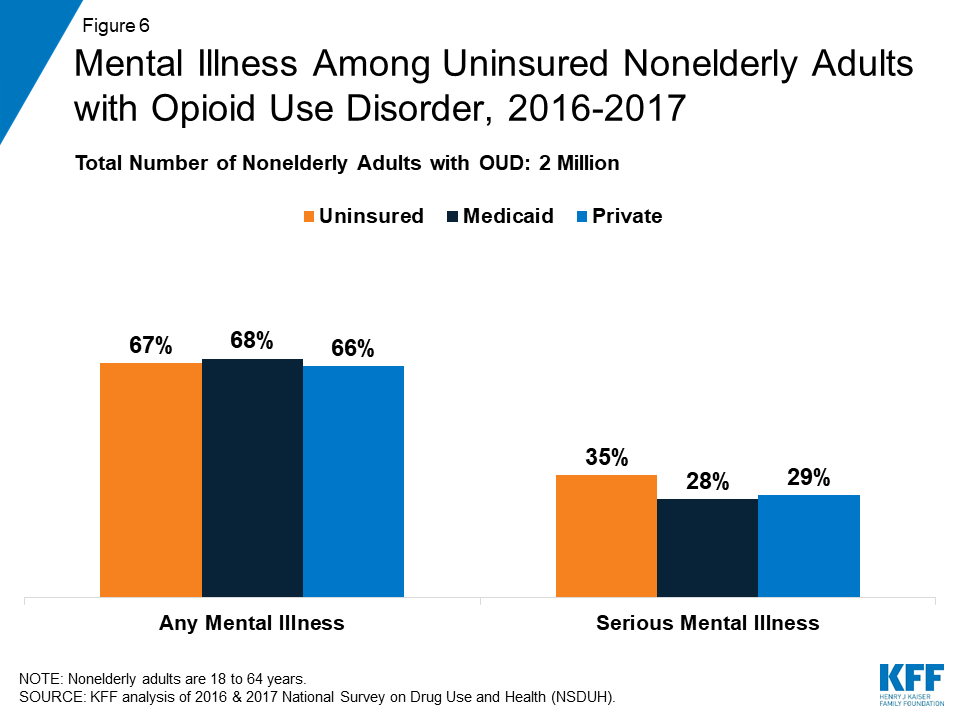

In the uninsured population, individuals with certain substance use disorders are likely to have co-occurring conditions. For example, from 2016 to 2017, 18 percent of Americans with an opioid use disorder were uninsured, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation study. In addition, most uninsured participants reported having a co-occurring mental health condition in the past year.

Three-quarters of adults with an opioid use disorder reported needing treatment but did not access treatment. Common reasons for not receiving treatment included lack of coverage and high treatment costs, among other causes.

The KFF study noted that uninsured individuals with opioid use disorders are highly vulnerable to overdose.

The second barrier to treatment that members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions may face is burdensome regulations and policies.

Although the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) and the Affordable Care Act successfully improved coverage for mental and behavioral healthcare related to substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) found that carve-outs remain a part of health insurance policies.

ASAM noted that insurance risk pools, clinician networks, and utilization management processes for mental and behavioral healthcare are still sometimes segregated from these aspects of medical coverage overall.

Finally, financial disincentives may create barriers in access to care for members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions. Certain types of providers earn more money when a patient returns for rehabilitation, giving them less incentive to prevent readmission.

One common financial obstacle occurs when a payer partners with a behavioral healthcare company to coordinate care for a member who also receives substance use disorder care from a primary care provider.

The primary care provider may code a visit as an addiction visit. As a result, the member’s bill can bounce between the behavioral healthcare organization, the primary care provider, and the member herself, leading to complications, errors, and confusion.

All these challenges are compounded for minority populations and individuals in under-resourced areas, NQF noted.

Institute quality measures that address co-occurring conditions

Quality measures are a valuable tool in advancing coverage priorities. Just as experts have recommended this approach for closing health equity gaps, NQF and Carney suggested that payers could implement quality measures to enhance coverage for substance abuse care with co-occurring conditions.

Carney had not encountered a health plan that had successfully tied specific quality measures to care for a substance use disorder with co-occurring conditions.

“The measures are pretty gross. They’re not refined yet to the way they need to be,” Carney explained. “The biggest tension in the payer community is about what can easily and accurately be measured.”

Part of the issue that payers have to confront is the ambiguity of a medical claim. A claim for a member with a substance use disorder and co-occurring condition does not tell a payer whether the provider administered evidence-based care and the provider’s approach

Chart reviews can provide more details on the nature and quality of a healthcare visit. However, the healthcare system also struggles to identify which entity should cover the cost of the chart review.

“The biggest tension in the payer community is about what can easily and accurately be measured.”

NQF noted several quality measures that payers could track to better serve their members with substance use disorders and co-occurring behavioral health conditions.

In particular, payers should explore leveraging risk adjustment to accommodate more individualized substance use disorder factors.

“Given the complexity of individuals with SUDs/OUD and co-occurring behavioral health conditions, failure to consider risk adjustment or stratification (e.g., by age, SES) could potentially penalize providers and health systems that care for higher-risk patient groups and populations,” the NQF report pointed out.

“Furthermore, risk adjustment can allow for a clearer pathway to understanding the needs of people with SUDs/OUD and concurrent behavioral health conditions.”

Social risk factors encompass many demographic measures that have been tied to substance use disorders, such as insurance, race, income, and housing instability.

“Given the correlation between deaths from polysubstance use and high levels of poverty, accurate benchmarks of economic and social challenges at the community level should be developed as a risk factor for SUDs in a given community,” the report stated.

Stratifying measures by provider type may further highlight areas for improvement, given the segregated nature of behavioral healthcare.

Use bundled payment plans

Reimbursing substance abuse care for a member with a co-occurring condition can be a complex matter. In order to streamline the endeavor and provide the right fiscal incentives, NQF and Carney recommended establishing bundled payment models that account for co-occurring conditions.

“Bundled payment models work because they tend to help reduce waste in terms of stacking codes or keeping people in the hospital longer than they should be,” Carney explained.

The cost for a potential readmission would be included in the episode of care. The provider would not receive a higher financial compensation if the member returns to the hospital after receiving care.

Under the traditional payment system, members with substance use disorders and co-occurring behavioral health conditions may receive medical care, behavioral healthcare, and their addiction care from three separate sources. As a result, neither care nor payment is coordinated.

The bundled payment model could work whether the co-occurring condition is a behavioral health condition or a medical condition such as sepsis from an infected injection site, Carney said. The payer would bundle all the services in a hospital encounter or all of the services within a certain number of outpatient visits into one episode of care.

“Bundled payment models work because they tend to help reduce waste in terms of stacking codes or keeping people in the hospital longer than they should be.”

Carney recommended that payers start exploring this method with residential substance use treatment. The episode of care might cover 30 to 90 days of treatment, including detoxification, treatment, drug testing, and behavioral healthcare. Such a model might reinforce evidence-based treatments such as medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

Putting together a bundled payment model for a substance use disorder with a co-occurring condition is more challenging than putting together a bundled payment model for a hip replacement, Carney acknowledged.

Still, Carney is not alone in considering this the next step in mental health and behavioral health reimbursement. The National Alliance Health has introduced mental and behavioral healthcare bundled payments as part of its episodes of care program.

Pursue more refined interoperability practices

Some of NQF’s recommendations naturally lend themselves to the health insurance industry’s overall movement toward interoperability.

“Payers have a wealth of patient data that they use to identify whether patients are at risk for overdose or mortality from SUD and/or behavioral health conditions. However, as individuals move through different stages of life and change health plans, this data and information do not move with the individual,” the NQF report noted.

“Stakeholders should identify opportunities to support data continuity across plans to leverage existing data in a manner that supports individuals who may be at risk of overdose or mortality.”

In particular, payers might leverage EHRs to help organize data on medical and behavioral conditions and treatment for members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions.

Additionally, implementing more integrated care models might streamline data transfer and create natural channels for sharing patient information between payers.

This mentality has been the primary driver behind the interoperability movement. Events such as switching jobs or changing from a parent’s health plan to a new individual plan require that the new payer receive data from the member’s previous payer. However, payers face many challenges in formulating a streamlined approach to exchanging members’ information.

CMS has directed payers to prepare for more substantial payer-to-payer data exchange. However, the agency recently backed away from enforcing this rule due to the administrative burden and challenges around data quality. Still, CMS and other experts have urged payers to continue building payer-to-payer exchange processes since these will be useful for other interoperability efforts.

“Payers have a wealth of patient data that they use to identify whether patients are at risk for overdose or mortality from SUD and/or behavioral health conditions."

Emergency service utilization can throw a wrench into payer interoperability efforts related to members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions.

When a member has a mental or behavioral healthcare emergency, they may contact 988 — a new emergency helpline for individuals with mental and behavioral conditions. The information from that healthcare encounter may be crucial for their overall care plan, but data from emergency care can be disorganized.

Payers should factor these complications into their strategies around members with substance use disorders and co-occurring conditions.

“Opportunities exist to encourage more consistent and thorough documentation of these critical aspects of care to better understand risk profiles for patients and related health outcomes,” the NQF report observed.

“When data are available, they can be difficult to interpret. Standardization of the reporting of EMS events could support measurement efforts and can help to identify which events are related to substance use and/or overdose.”

Cover harm reduction services

Harm reduction services can be a crucial element of substance abuse care for those with co-occurring mental or behavioral healthcare needs. Alcohol and substance abuse have been tied to suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and other mental health risks such as social and financial challenges.

The methods used to avert harm due to substance use will vary among members.

The National Harm Reduction Coalition’s site emphasizes that the individual and societal circumstances around drug use are unique for each individual, requiring a personalized approach. Generally, however, the organization’s principles of harm reduction refer to both preventive strategies that reduce risk and a movement to reform social perspectives on drug use.

Carney stressed that — regardless of what the intervention is — the payer industry and their provider partners need to move toward policies that emphasize documented, evidence-based harm reduction practices.

“Payers can explore their ability to reimburse for the provision of harm reduction services, including syringe service programs, naloxone distribution and overdose education, and/or drug testing services,” the NQF report stated.

Until a more formalized approach becomes standard — such as a CPT code for harm reduction counseling — payers may have to increase chart reviews related to harm reduction, Carney shared.

Offer enrollment assistance programs for individuals leaving the justice system

The NQF report noted that individuals in the criminal justice system are unlikely to receive strong interventions such as medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) while they are inside the system or once they leave the system.

“While Medicaid expansion has been associated with improving rates of MOUD post-incarceration, enrollment assistance programs are likely necessary to increase rates of effective insurance coverage at release,” the report stated.

Compared to states that had not expanded their Medicaid programs, Medicaid expansion states experienced a six percent drop in total opioid overdose deaths between 2001 and 2017. Researchers attributed the decline to more extensive coverage for opioid use disorders in Medicaid expansion states.

States have already started exploring ways to ensure that incarcerated individuals have access to coverage after leaving the justice system. During the coronavirus pandemic, states employed strategies like starting the Medicaid eligibility determination process before release or suspending — instead of terminating — Medicaid coverage during incarceration.

Stable coverage for substance abuse care could be particularly meaningful for patients in the justice system. The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimated that 65 percent of individuals in the US prison system have an active substance use disorder.

Without coverage for medication and treatment, these individuals may not be able to afford care. When individuals forego substance abuse care, patient outcomes and healthcare spending suffer.

While the NQF report highlighted many areas of uncertainty and opportunity for improvement, Carney found that the report itself signaled progress.

“The most important thing is that there is now a national document that says we cannot treat conditions in silos, we have to look holistically at the individual,” Carney said.

“I am hopeful for the future. Every time we have more awareness about the struggles that people are having to get evidence-based care, we are able to move the needle forward in solving for those problems.”

NQF has received funding from the Department of Health and Human Services to run the Opioids and Behavioral Health committee for another year to shed more light on this complex issue.